Opera Album Review: August Enna’s Wagnerian “Kleopatra” — Revived on Danish Soil After 122 Years

By Ralph P. Locke

August Enna’s colorful and vividly melodramatic score does justice to the robust exoticism of H. Rider Haggard’s novel.

August Enna: Kleopatra (opera)

Elsebeth Dreisig (Kleopatra), Ruslana Koval (Charmion), Magnus Vigilius (Harmaki), Lars Møller (Sepa), Jens Bové (Schafra).

Odense Symphony and Danish National Opera Chorus, cond. Joachim Gustafsson.

Dacapo Records 226708 [2 CDs] 111 minutes

Opera performances today often involve a mix of singers from many different lands, trying to interact plausibly with each other in a language that few if any of them know well.

Opera performances today often involve a mix of singers from many different lands, trying to interact plausibly with each other in a language that few if any of them know well.

I have been welcoming, here and at other internet magazines, a number of operas that show how it can be done differently, and (I’d argue) often more effectively: an opera in language X, performed wholly (or mainly) by singers who are native speakers. I gave a hearty welcome to new and recent operas by two Americans (Carlisle Floyd, Emerson College’s Scott Wheeler), an 84-year-old (or -young!) pro-union theater work by Marc Blitzstein (The Cradle Will Rock), a century-old opera in three shortish scenes by the Spanish master Enrique Granados (better known as a composer for piano), the best-known Croatian operas (by Jakov Gotovac), and a marvelous fairy-tale opera in Swedish by Laci Boldemann. Indeed, the list goes on: Grétry, Offenbach, Vaughan Williams (adapting Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor), John Joubert (Jane Eyre), and many more.

In all of these, the strengths of the work were magnified by the singers’ easy command of, and evident identification with, the words they were singing. Endless fine nuances of text delivery enriched what might have been capable but somewhat flat renditions, had the singers been a mixed bag of foreigners (however proficient, even astounding, their voice production).

What I just wrote in the three paragraphs above may sound like some kind of reactionary nativism — a symptom of the xenophobia that has been wreaking havoc in the body politic in the US and elsewhere in recent years.

But it isn’t. It’s a recognition that national traditions have their own validity. We expect that a Broadway musical will be performed by native English-speakers, for whom the text is crucial and multilayered: performers such as (c. 1985) Bernadette Peters and Mandy Patinkin or (in recent years) Kelli O’Hara and Daveed Diggs. Why not opera?

I am therefore delighted to welcome this world-premiere recording of a once-famous opera from Denmark: August Enna’s Kleopatra, first performed in Copenhagen in 1894.

Determined record collectors, but few others, will recognize the name of August Enna. The past few decades have seen the release of two of his operas (Young Love and The Little Match Girl) and a CD of orchestral works. But this long-lived and once-renowned Danish composer (1859-1939) composed 12 other operas. And the most famous of them all is the present one, based on the wildly popular 1889 adventure novel by English author H. Rider Haggard, Cleopatra: Being an Account of the Fall and Vengeance of Harmachis.

Enna is an odd name for a Dane. The family was originally from Italy; the father, a shoemaker. August, largely self-trained in music, was devoted in particular to the works of Wagner and — an odd bedfellow for Wagner — the French opera and ballet composer Léo Delibes.

Kleopatra (the name is accented on the second syllable) was a semi-failure at its first performances in 1894, but it triumphed a year later when Queen Kleopatra and her handmaiden Charmion were sung by the sopranos for whom Enna had originally intended the roles. It reportedly also “met with huge success in Berlin, Hamburg, Cologne,” and other cities, including — if one can believe the booklet-essay — 50 performances in a single year (1897) in Amsterdam.

Kleopatra (the name is accented on the second syllable) was a semi-failure at its first performances in 1894, but it triumphed a year later when Queen Kleopatra and her handmaiden Charmion were sung by the sopranos for whom Enna had originally intended the roles. It reportedly also “met with huge success in Berlin, Hamburg, Cologne,” and other cities, including — if one can believe the booklet-essay — 50 performances in a single year (1897) in Amsterdam.

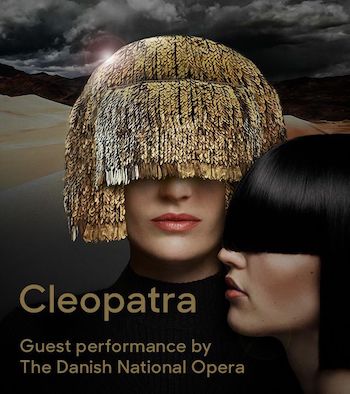

But modernism soon came to Danish musical life with Carl Nielsen. Straightforward Romanticism now seemed, to many, dusty and, perhaps, provincial. (This was odd, in a way, because that traditional Romantic style was itself highly cosmopolitan, as Enna showed by taking Wagner and Delibes as twin models.) Kleopatra and the rest of his works gradually vanished. The 2019 production at the Danish National Opera — source of the present recording– marked the work’s first performance in 122 years on Danish soil.

We are lucky that Dacapo and the Danish Broadcasting Corporation recorded those performances: the CD set goes far toward vindicating Enna and his vision of a native musical life that could stand shoulder to shoulder with what was being done in European lands then recognized as more obviously “major.” Enna’s style in Kleopatra reminds me of Wagner’s operas from some 50 years earlier (mainly The Flying Dutchman and Tannhäuser), enriched with numerous decorative orchestral touches that evoke French and Italian models. Charmion’s Act 1 lament contains a little piping oboe figure with grace note that comes right out of Aida. Several duets, such as for Charmion and Harmaki (Act 2), end with persuasively energetic cabaletta-like sections, much like those in Italian and French operas of the previous half-century. In general, the vocal lines lie comfortably on the voice and display (in William H. Reynolds’s apt phrase, in Grove) Enna’s “easy melodic gift.”

I was often captivated by short orchestral commentaries preceding or following some statement by a character: surging arpeggiated figures from the strings, emphatic declaiming from the brass, querulous doubts from the winds. Enna knows just when to have the orchestra double the voice (much as Puccini was doing around the same time). One notable case of the latter technique occurs when the high priest Sepa demands (in Act 1, scene 1) that Harmaki (the heir to the pharaonic throne) be firm in his plan of murdering Kleopatra and thereby freeing Egypt from Roman control.

The opera is tightly constructed. The plot is straightforward and clear. Each moment makes its point and then moves on. The three acts (officially two, preceded by a three-scene prologue, here oddly translated “Overture”) take an hour and 50 minutes, making the work far shorter than most Wagner operas or French grand operas. And eight of those minutes are a lovely ballet sequence that could be omitted but I hope won’t ever be. This ballet would also work well on a pops-orchestra concert.

Harmaki — to summarize the plot briefly — enters Kleopatra’s court in disguise as an astrologer, for she has called for someone who might interpret her dream. (Haggard presumably was adding a bit of the biblical Joseph into the story.) Kleopatra instantly falls in love with her would-be murderer. He gradually weakens. Her maidservant Charmion, who likewise loves Harmaki, tries to persuade him to be loyal to his people. He rejects her.

A scene from the 2019 Danish National Opera production of Kleopatra. Photo: Dacapo.

Charmion then reveals his plot to Kleopatra, who arrests Charmion’s father (the high priest Sepa) and the other conspirators. Harmaki stabs himself with the dagger with which he had once intended to murder Kleopatra, as Charmion — who loved him but betrayed him — collapses on top of him, “heartbroken,” in a melodious love-death that would make a fine concert aria (less than four minutes). Among other effective theatrical details are a veil that Charmion accidentally drops (and that the queen, of course, finds) and a wreath of hyacinths that the queen places on Harmaki’s head in Act 1 and that, in Act 2, the latter flings to the floor, then gathers to his breast (a bit like Bizet’s Don José with Carmen’s flower).

All of this comes across extraordinarily well in the Dacapo recording, made during three performances in the Odense Concert House. The balance between voices and orchestra is marvelous: I could hear everything with ease, and the voices of the five main singers largely cajoled my ears while conveying vividly the meaning of the words. It surely helps that four of them are Danes. (The Charmion is Ukrainian.) Be careful: Elsebeth Dreisig, a fine lyric-dramatic, should not be confused with the lighter soprano from Belgium with a similar name, Elsa Dreisig, whom I have praised here in Massenet’s Spanish-tinged comic opera Don César de Bazan.

If we are ready now to discover the virtues of other mainstream opera composers from the mid and late 19th century that I have reviewed here in recent years (by, say F. Lachner, Bruch, David, Gounod, Saint-Saens, Godard, Lalo), why not Enna or another Scandinavian, Olander (his opera about a mythical Swedish heroine, Blenda)?

The booklet contains a fine essay and the libretto, all translated well except for too-literal transposition of verb tenses (overuse of the historical present, and too much “has been” for “was”). If you prefer to stream the recording (e.g., on Spotify), you can download the booklet from the Dacapo site for free. The site also has two great videos about the project, and you can stream the beginning of each track there as well.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.