Book Review: “Broadway Goes to War — American Theater during World War II”

By Joan Lancourt

For many dramatists, the label of “leftism” was not pejorative: it was about fighting for human decency and political reform.

Broadway Goes to War: American Theater during World War II by Robert L. McLaughlin and Sally E. Parry. The University Press of Kentucky, 300 pages, $35.

We tend to think of WWII as a time in US history when every man, woman, and child was united in support of the war effort: 12 million men joined the military, millions of women and African Americans replaced them in the workforce, people bought war bonds, and 90 million people went to the movies every week as Hollywood pumped out a stream of patriotic films filled with messages offered by the US Office of War Information.

We tend to think of WWII as a time in US history when every man, woman, and child was united in support of the war effort: 12 million men joined the military, millions of women and African Americans replaced them in the workforce, people bought war bonds, and 90 million people went to the movies every week as Hollywood pumped out a stream of patriotic films filled with messages offered by the US Office of War Information.

According to Robert L. McLaughlin and Sally E. Parry in Broadway Goes to War, reality presented a significantly different picture. Their book opens with a description of the 22,000 cheering supporters of the German American Bund’s 1939 Washington’s Birthday celebration at Madison Square Garden. Outside, in response to 10,000 people protesting the Bund event, were 1,700 police assigned to keep the peace. The post-Depression hope of “getting back to normal” had instead given way to deep divisions: the rise of fascism meant that democracy was in imminent peril; the possibility of war sparked powerful demands for isolationism and pacifism. The call to support US allies generated daily tensions, and there was little agreement about what the US role should be in world affairs.

Unlike Hollywood, the authors suggest that Broadway theater offered a more accurate picture of what was actually going on in people’s minds — about the military, about the war’s impact on the home front in terms of gender roles, sexual mores, juvenile delinquency, and what kind of country America would be when the war was over. It was a time of confusion and uncertainty; it was difficult to make sense of the news and there was no clear path into the future. Theater, the authors argue, was less censored than Hollywood and not as dependent as radio on sponsors. Serious playwrights used the stage to explore various political concerns. McLaughlin and Parry organize their useful examination of Broadway plays from 1933 to 1947 into five chapters: Popular Culture, Before Pearl Harbor, Overseas, The Home Front, and Anticipating the Postwar World.

In the post-Depression era, theater was far more political than it had been in the ’20s. Scripts raised issues about class, the distribution of wealth, the failure of capitalism, the rise of demagogues like Father Coughlin, and a broad array of social tensions, including gender and race. It was a time of political and cultural upheaval: with the advent of the draft, social roles were redefined and economic and racial divisions had become deeper.

McLaughlin and Parry write that “it didn’t require … Moscow to compel American playwrights to write against poverty, injustice or war.” The Little Theater movement and the workers’ theaters of the ’30s were committed to the “essential social and moral issues of their times.” For many dramatists, the label of “leftism” was not pejorative: it was about fighting for human decency and political reform. Theater had the power to inspire change, and the mission for playwrights was to “get the message out.” McLaughlin and Parry also show that these didactic messages were part of larger narratives that explored ways to think about, and answer, the “big questions.” The plays delved into why the US was fighting; why it had to support its allies; and why everyone had an individual responsibility to contribute to the ultimate victory.

These assessments are supported through an examination of specific plays. They range from the 1935 antiwar If This Be Treason, which asks “why do people always choose war in a crisis?” (The playwright’s answer: “Because they are never given the real opportunity to choose anything else. What if peace had a decent chance?”) to the 1946 Pulitzer Prize–winning State of the Union, loosely based on the presidential campaign of Henry A. Wallace. The latter offered a love-triangle, and a tug of war between the “politicians and the people,” the former accusing the latter of having “abrogated their responsibility to be informed participants in the democratic process.” Still, the drama ends with an affirmation of democracy: “Darling, you’re right about the future. We’ve got something great to work for.”

Along the way, the authors examine scripts that take up the self-serving motives and mendacity behind government war rhetoric, the danger of ideals and causes, and debates about what one should be willing to die for. A number of plays define fascism’s threat to democracy and its savage violation of elemental human rights. Plots focus on characters fleeing fascism to escape physical harm, the plight of broken families, and the anticipated challenge of rehabilitating those who had been “brainwashed” by fascist thinking. Plots also focused on home-grown fascism. The Ghost of Yankee Doodle concentrated on the conflict between ideals and craven self-interest, while Sherwood’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Idiot’s Delight delved into knee-jerk nationalism. John Steinbeck’s 1942 The Moon Is Down tackled the appeal of freedom, power, resistance, and individuality, posing the question of whether power flowed from the top down (Germany) or from the bottom up (Norway)?

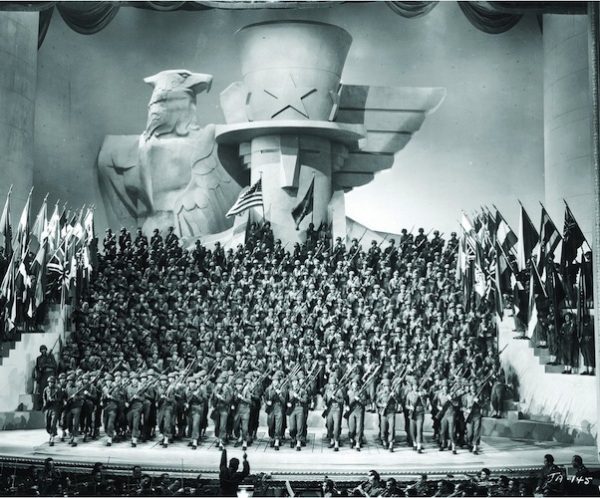

A scene from 1943’s Irving Berlin extravaganza, This Is the Army.

And of course, there were numerous plays about the military, such as Berlin’s This Is The Army, a musical extravaganza of over 300, performed entirely by army personnel, which included the first integrated unit in the army, and Let’s Face It, Cole Porter’s 1941 musical comedy about draftees. Still others showed how the military turned ordinary men into a massive fighting force, or how ordinary men democratized the military. The play The Streets Are Guarded concludes that the real experience of war can never be transmitted to noncombatants; in fact, it can never be completely understood, even by those who participated directly. And, toward the war’s end, it became clear that no one could pretend that nothing had changed. Women’s roles, for example, had been fundamentally altered. Maxwell Anderson’s Truckline Cafe dramatized the impossibility of picking up where America had left off, but despite the many changes, Rose Franken’s Soldier’s Wife resolved the new tensions with the wife giving up her newfound opportunities in order to save her marriage.

Race and home-grown anti-Semitism posed two other disturbing issues. The cast of Bernstein’s On The Town was uncharacteristically multiracial, imagining “an America of open minded inclusion, free of racial bias and boundaries.” Reality, of course, was entirely different. Yet, the four Broadway plays that addressed these issues were written by white playwrights who were sympathetic, but lacking in heart and soul. The 1946 script On Whitman Avenue takes place in the North, and looked critically at the powerful monied interests who had a stake in maintaining the separation of the races, with one character exclaiming, “I don’t know a nice way of saying you can fight for your country, but you can’t live in it.” And 1943’s Kurt Weill and Moss Hart’s musical We Will Never Die, staged at Madison Square Garden, ended with a dramatic recitation of the Kaddish by 50 elderly European rabbis, acknowledging America’s shameful refusal to help European Jewry.

The book provides brief synopses of 212 Broadway plays from 1933 to 1947, with in-depth analysis of selected plays that dramatized key issues. In retrospect, most of the scripts are not particularly memorable, (nor, I suspect, will most of today’s Broadway fare be hailed 80+ years from now). Even some of those considered at the time to be masterpieces, such as Lillian Hellman’s Watch on the Rhine, which addresses the loss of American innocence, today comes off as contrived. Plots were often based on a steady stream of improbable coincidences, convenient appearances and disappearances, predictable responses and outcomes, and stock, one-dimensional characters from multiple walks of life, placed in artificial situations (hotel lobbies, an airplane, a troop of USO performers, etc.). The goal was to spotlight an array of simplified, opposing ideologies or uplifting points of view. S. N. Behrman’s No Time for Comedy included lines like “The difficult thing is to live — that requires skill.” Or, “To live where there is freedom, Karl, that is the greatest thing in the world,” runs a snippet of dialogue in Kaufman and Hart’s The American Way, a musical extravaganza that celebrates the American Dream and the ongoing need to defend freedom. Irwin Shaw’s The Gentle People suggests that fascism is endemic to US culture: “That’s the way the world is made, Pop. The strong take from the weak.” And in Frederick Brennan’s The Wookey, we hear, “Wot am I fightin’ for but them [his children]? Wot comes outer this war but them an’ the free life better men than me is dyin’ ter give them?”

A 2008 revival of Irwin Shaw’s 1936 play Bury the Dead at LA’s Actors’ Gang theater. Photo: Jean-Louis Darville.

One interesting exception to these contrived plots and platitudes was Irwin Shaw’s 1936 Bury the Dead. In it, “six soldiers killed in battle stand up in their mass grave and refuse to be buried.” The military tries to suppress news of this insubordination; the clergy attempt to exorcise their demons; and attending officers, in a frustrated rage, machine gun the already dead. In death, the men realize the folly of dying for “patriotism” or someone else’s cause. What they are really protesting is how little they had been able to partake of the mundane pleasures of everyday life. One long-suffering wife cries out, “What took you so long? Why didn’t you stand up while you were still alive.”

Kudos to the authors for gathering, organizing, and analyzing a massive amount of material, highlighting important themes, and making it accessible to anyone interested in theater, American history, sociology, WWII politics, and human nature.

Joan Lancourt, Ph.D. is a retired organizational change consultant, a former theater board chair, and a recent chair of the Brookline Commission for Diversity, Inclusion & Community Relations. She consults and has run workshops on increasing theater board diversity and community engagement, and is currently writing a book on Junior Programs, Inc, 1936-43, one of the first major professional performing arts companies devoted exclusively to theater, opera and dance performances for young audiences.

Tagged: Broadway Goes to War: American Theater during World War II, Joan Lancourt