Theater Review: “Evening at the Talk House” — Amusing Ourselves to Dystopia

Evening at the Talk House is a savage indictment of our country’s acceptance of the immense, horrific violence necessary to maintain our consumer comforts.

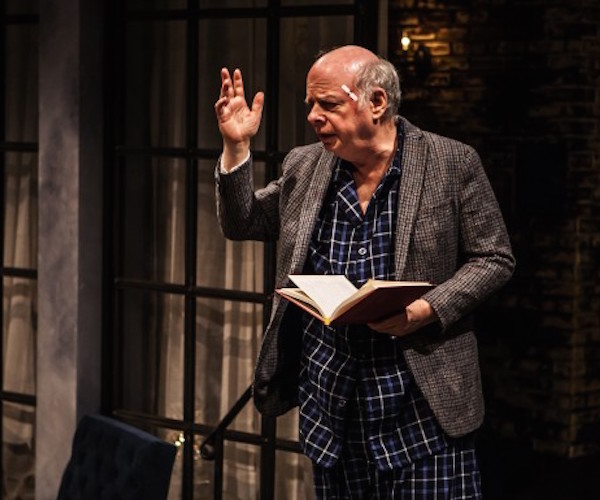

Wallace Shawn in the New York production of his play “Evening at the Talk House.” Photo: Monique Carboni.

By Lucas Spiro

Sometimes the only way to get a point across is to ruin a dinner party. But creating disaster is an art; success often depends on a careful intake of booze, the ability to wittily critique the vacuous (yet dangerous) opinions of those around you, and a political position that lies somewhere outside of the bromides of television talking heads. It helps to have the truth on your side, but that’s hard to come by. The vital component: the will to shout unpleasant truths futilely into the void.

If you want to hear how it is done, listen to the radio production (for free) of Wallace Shawn’s play Evening at the Talk House, produced by Jeremy Scahill’s Intercepted podcast. Frankly, the show ought to be heard by everyone who dares to have an opinion, whether iconoclastic or establishment, about anything. This script offers one of the most savage indictments yet of our country’s passive acceptance of the immense, horrific violence necessary to maintain our consumer comforts, our ‘way of life,’ rooted in our right to enjoy tasteful dinner parties.

Evening at the Talk House is a play about a reunion, a quiet gathering ruined in a spectacular fashion. Former dramatist Robert (Matthew Broderick) has been invited to celebrate the tenth anniversary of his play Midnight in a Clearing with Moon and Stars. The script was panned by critics, unappreciated by audiences, and Robert left the theater for good, becoming head writer for the popular television program Tony and Company, an escapist production that epitomizes the spirit of the powerful people who control not only politics, economics, and war, but also art and culture.

Robert works on the show with “gorgeous and resplendent” Tom (Larry Pine), who was the lead in Midnight and who also plays Tony. Also in attendance are Ted (John Epperson), a musician who wrote occasional music for Robert’s plays, but currently writes jingles and does other odd jobs. Partygoer and costume designer Annette (Claudia Shear) is “a special friend and confidant,” someone the group could “always count on,” a “pleasant and calm” personality who now only has infrequent “high end custom tailor” jobs. The other attendees include the successful talent agent and producer Bill (Michael Tucker) and Nelly and Jane, who run the Talk House, a “quiet and genteel club.” The Talk House was a major hub for what was once a vibrant theater scene, but it has fallen on hard times because the theater is on life support in our age of technological entertainment. Those who have money are attracted by the new and the fancy.

A clear economic division has established itself over the past decade. This once close group of friends are now starkly divided: on the one hand, there are those who are wealthy and successful, usually through nepotism; on the other hand there are those who have been forced to succumb to precarious employment in the ‘gig’ economy.

Robert’s plays always took place in an “imagined medieval world with noble knights and fair maidens,” populated by characters who championed “perennially threatened ideals” that the writer admired. In his conversation with Scahill on the podcast, Shawn confesses that he would like to be able to believe in those same ideals: “self-sacrifice, courage, loyalty, suffering in preference to dishonor.” But he argues that, if twisted or put blindly in service of the malicious, these ideals can easily become fascistic, a process Shawn is deeply concerned about and dramatizes in this play.

Just as the world of Robert’s scripts were set in an imagined, somewhat ethereal world, the Talk House is also an unreal place, a territory where every anxiety, every fear, is slightly distorted to reveal its controlling power more clearly. Dick, played by Shawn, explains the nature of the Talk House after he runs into Robert (Dick was not invited to the reunion). He looks at the other guests and says the feeling he gets is like falling asleep in an overheated room and you “dream you’re surrounded by the most horrible people you’ve ever met in your life. Or, to put it a bit differently, you’re surrounded by all your favorite people and you’re absolutely thrilled.”

This dreamlike, actually nightmarish, quality, bedeviled by paradox, is deftly evoked in the Intercepted podcast production (the script received a New York staging in early 2017). The dialogue is vintage Shawn; direct, often simple language that on occasion reaches out toward some more abstract or elusive form of expression. We hear what is deeply troubling him about the state of the world today. His recent small collection of essays Night Thoughts (Haymarket Books) also dwells on some of these issues: his anxious, at times somewhat naïve, analysis muses on murder, from individual cases to genocide, and moves onto the immorality of economic inequality and then the omnipresence of violence — the mindless destruction waged by individuals, the terrorist, and the state.

State violence particularly concerns those in Talk House. What dooms dinner parties? Politics. Our paralyzed society, with its spectacle of a troubled democracy maintaining its power through various forms of violence, is among the conversation’s top topics. Tom supports, though he has reservations about, what he calls “that program of murdering,” a state initiative of killing through a system called “targeting” that eliminates people that might want to do harm to the citizens of the Homeland. This policy is not limited to foreign enemies, though. He is complicit with a culture of murder in which getting rid of undesirable, nonconformist, or anti-social types is acceptable. Consumption must be protected.

A debate follows that revolves around the absurdity of believing that the state can do whatever it wants for the sake of National Security. Annette argues that it is “merely a question of policy,” like environmental regulations or zoning laws. And she goes on to suggest that the disappeared don’t add up to “an enormous number of lives.” Widespread state murder is seen as “unavoidable,” comparing it to the act of taking a shit: these “rather small bombs” kill people in a way that “takes very little time, [is] barely noticeable, [is] something everyone does, and largely inconsequential.” Tom wonders whether we can “really be sure that we’re murdering the right people,” to which Annette responds that “we’re getting awfully good at determining that,” something she knows firsthand because she admits to having helped with “targeting” on behalf of the government because it pays better and more regularly than her work in the gig economy.

A scene from the 2017 New York production of Wallace Shawn’s “Evening at the Talk House.” Photo: Monique Carboni.

Shawn brilliantly exposes American hypocrisy. We make money and take comfort from acts of murder that are treated as a matter of abstract policy. He is no doubt referring to the anti-terrorist drone program that the Obama administration pioneered and perfected under the guidance of former CIA head John O. Brennan. Collateral damage is inevitable; the casual loss of innocent lives is a sure byproduct. Drones are “rather small bombs,” doing the unpleasant work of “technocrats [who] have devoted their lives to” [d]eciphering the exact difference between some resentful guy and some other guy who may outwardly seem like the other guy.” The talk in the Talk House, its surreality, is symptomatic of the culture of fear that our government uses to justify the use of force, including actions that violate international law and our own Constitution.

The debate at the Talk House predictably descends into chaos, and that makes sense. There are no unifying solutions available, only more division. Still, Shawn hopes that when you wake up from his nightmare, when you leave that theater, you realize that you have choices to make. Not so that you might become ‘woke,’ but awakened to the dialectic of theater, to the fact that, if this is the order of things today, then there is only one simple question to ask: “what is to be done?” In Night Thoughts, Shawn meditates on section of Bertolt Brecht’s 1935 poem “Questions From a Worker Who Reads”:

Wer baute das sieben-törige Theben?

In den Büchen stehen die Namen von

Königen.

Haben die Königen die Feslenbrocken

herbeigeschleppt?…

Who built Thebes with its seven gates?

In books, we’re given the names of kings.

Did the kings carry on their own backs

Those massive fragments of stone?…

Shawn has recently completed a new translation of The Threepenny Opera, so it follows that a Brechtian approach to culture and politics — using art to encourage taking action — are on his mind. After Scahill saw Evening at the Talk House in New York, he walked to the subway along 5th Avenue, with its shop windows filled with expensive clothing and electronic gadgets. He wondered whether anything would change if (in the window) we were made to watch a live stream of the young girl in Bangladesh, or the young worker in the Chinese factory, or the child in Africa mining cobalt for your smart phone. What if the veil between easy consumption and reality was pulled back. What if more of our dinner parties were ruined by seeing how much misery sustains our comfortable lifestyle? What if we had a constructive way of accepting that murder and misery were the foundations of “our way of life?” Would we change anything? I’m not convinced we would. Shawn’s play is a welcome, challenging sign, though I fear that it is just one more shout in the void, une pièce égaré dans le cosmos.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living outside Boston. He studied Irish literature at Trinity College Dublin and his fiction has appeared in the Watermark. Generally, he despairs. Occassionally, he is joyous.

Tagged: Evening at the Talk House, Lucas Spiro, The Intercept

I Love love love Wallace Shawn, talented, funny , engaging… Met him while working at Cafe’ Paswual’s!

This is a wonderful analysis of the play. I drove to New York last year to see The New Group stage production. As the audience entered the two-sided stadium seating of the theater at Linney Courtyard Theater at Signature Place, they found the cast milling around the stage area passing out candy to anyone inclined to come up and talk to them. How appropriate! We got sweets before the show knowing the play would not leave us feeling warm and fuzzy when all was said (and done).

I spoke to Shawn afterward in the lobby telling him I had ordered and read the play in advance. I had memorized the long opening monologue for fun just to absorb Shawn’s wonderfully barbed language. He signed the book for me and was pleased to hear I had driven from Boston for Aunt Dan and Lemon, The Designated Mourner, and Grasses of a Thousand Colors when each played at the Public. He seemed taken aback. “My you are a curiosity. It is so nice to meet you” he said.

Shawn is a joy on stage. In the latter two plays, he himself took lead. Both were directed by Andre Gregory. Shawn leaves the house lights on and the audience are given programs after the play so they will pay attention during the performance. He addresses the audience directly. When in the middle of his opening monologue for Grasses of a Thousand Colors (which was a veiled tirade about his famous father) an audience member entered late. He stopped, looked at the tardy patron, and said — “Thank you for coming. Take a seat. Would you like me to catch you up on where we are in the play?” He proceeded to make up an entirely different scenario and then to weave it back to where he had left off. I had read it in advance so I knew he was off script but many assumed it was part of the (very bizarre) play.

I didn’t know about this podcast version of Evening at the Talk House. Thanks for the commentary! I can’t get enough of this unique and wonderful playwright.