Rethinking the Repertoire #21– Alban Berg’s “Altenberg-Lieder”

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the twentieth in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg. Photo: Wiki

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The big musical riot in the early 20th century wasn’t, as most would have it, the May 29th, 1913 premiere of The Rite of Spring. That was, certainly, seismic, but the event had far more to do with Vaslav Nijinsky’s radical choreography than with Stravinsky’s score, which, despite its aggressive dissonances and complex rhythmic schemes, has proven popular with audiences since its debut as a concert work in early 1914.

No, for a brouhaha provoked by the music itself, you have to travel back a few weeks and 700-some miles to the southeast to Vienna on March 31st, 1913. There you had what’s gone down in history as the Skandalkonzert, a program of modern music conducted by Arnold Schoenberg that never actually finished: its second half devolved into a melee that the police were called in to break up and the night ended early for everybody. The piece that lit the spark for the fisticuffs that followed? None other than Alban Berg’s Altenberg-Lieder.

At the time, Berg, just turned twenty-seven, was striking out on his own as a composer. The Piano Sonata and Seven Early Songs date from the eight years before it and the next two major works to follow Altenberg are among his most important: the Three Pieces for Orchestra and Wozzeck. Yet the Lieder have been largely neglected. Why that fate and not, say, The Rite of Spring’s?

There are a few reasons, both owing to Berg’s insecurities as a composer at the time and the fallout from its partial premiere (the Skandalkonzert featured just two of its five movements).

To begin, the Altenberg-Lieder marked the first time he wrote for orchestra. And Berg, deeply impressed by Schoenberg’s own Five Pieces for Orchestra, had decided that, in his orchestral debut, he wanted to hold nothing back. He didn’t. Unfortunately, Schoenberg, Berg’s mentor and teacher, seems to have felt threatened by the sheer brilliance of Berg’s scoring in the Lieder – as we shall see and hear, it’s staggeringly iridescent – and his lukewarm response to the work gave the younger composer pause.

Poet Peter Altenberg. Photo: Wiki

Then there was his choice of texts. In the Lieder, Berg set five aphoristic poems by Peter Altenberg, a leading light of the fin de siècle Jung-Wien (“Young Vienna”) movement. They’re sometimes ironic, sometimes funny, sometimes genuinely moving. Berg’s settings are all rather straightforward. However, at that March concert, the enigmatic nature of the poems and the perceived earnestness of the music, coupled with Berg’s Modernist language and a dyspeptic audience waiting to pounce (they’d already hissed Schoenberg’s chromatic but tonal Chamber Symphony no. 1) made for a nasty result. Perhaps in response, Berg’s subsequent vocal works draw on more familiar poets (Theodor Storm and Charles Baudelaire).

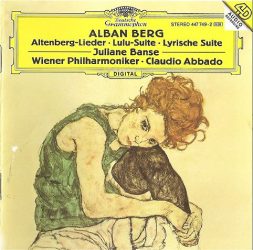

Finally, there’s Schoenberg’s response to the Skandalkonzert, particularly Berg’s role in it. Sometime during the summer of 1913, he gave Berg a thorough dressing down for the Lieder. The reasons for his outburst remain obscure but they provoked a subservient letter of apology from Berg and he basically shelved the piece. It wasn’t heard in full until the early 1950s and the orchestral score was not published until 1966. Since then, it’s been occasionally performed – Pierre Boulez and Claudio Abbado both championed it – but it remains a niche piece in the Berg catalogue (the Boston Symphony’s played it twice, once with Evelyn Lear and Erich Leinsdorf in 1966, then with Roberta Alexander and Michael Tilson Thomas in 1987; Daniele Gatti led the most recent New York Philharmonic performance in 2002 with Christine Schäfer).

That neglect, though, is our loss. The Altenberg-Lieder feature Berg at his most direct and concise, as well as his most sumptuous.

On an intellectual level, they dazzle. The first and last songs share a pair of melodies that sound nothing alike but are drawn from the same pitch material organized to follow the same succession of intervals. Further, there’s a striking symmetry between those movements’ respective harmonic materials, which, in the first, proceeds from one five-note chord to another as the music increases in volume from pianissimo to fortississimo; in the last, the progression and dynamic shapes are reversed. Symmetrical concerns also mark the central lied, which opens with a dense woodwind chord that unwinds, note by note – only to be built up again by the strings as the song comes to its end.

But, striking though Berg’s abstract gestures might be – and, given how audible it is what he’s doing, they pack dramatic potency, as well – the Lieder are of course nothing if they don’t speak on an expressive, musical level. And this they do.

Part of the reason for this owes to the directness of Berg’s text settings. Altenberg’s poems, as one scholar notes, make no effort to clarify their ironies: are they serious? Maudlin? Something in between? Is the ambiguity intentional or not? Those determinations are left to the reader. And Berg didn’t emphasize one interpretation over the other: his settings are essentially forthright musical depictions of the ideas and images the poems present.

What’s more, his command of the orchestra in the Lieder (as noted earlier) was total. Essentially, Berg treated the ensemble as a gigantic chamber group, drawing an array of colors and instrumental combinations from his colossal forces (triple woodwinds and brass – quadruple horns and trombones, actually – plus four percussion, harp, two keyboards, and strings).

At times, the orchestra simply glows. The opening song, “Seele, wie bist du schöner,” begins with a shimmer: a falling piccolo/clarinet melody echoed by percussion that’s accompanied by scurrying, rhythmically disjunct ellipses in the rest of the ensemble. Eventually, everybody (or just about) combines in a wild, descending line that disintegrates as it falls; after that stunning introduction, the voice enters.

Throughout the Lieder, Berg’s sheer enthusiasm for fresh-sounding music and gestures is on display. It’s there in the penultimate gesture of the first song, an ethereal whoosh of violin harmonics that comes out of nowhere. So, too, in the delicate scoring of the second, “Sahst du nach dem Gewitterregen den Wald,” with its anticipations of Webern’s spare textures; and in the third (“Über die Grenzen des All”) whose outer, foggy chords frame a series of terse, triplet rhythms.

Also abundantly in evidence is Berg’s ability to craft a musical argument of serious weight. That’s most clear in the last of the Lieder’s movements, “Hier ist Friede.” Set as a passacaglia (a set of variations over a recurring bass line), it moves from rhythmic and harmonic simplicity to complexity, its apex marked – in stunning fashion – by the orchestra landing on an emphatic A major triad. Things proceed backwards from there: chromaticism intrudes, textures become murky, and the music gradually dies away. But this four-and-a-half-minute meditation on finding peace in a world of sorrow and suffering is cut from the same dramatic and emotional cloth that we’re familiar with from later Berg classics, like Wozzeck, Lulu, and the Lyric Suite.

In all, then, the Altenberg-Lieder are far more than a curiosity in Berg’s catalogue. Quite the opposite: they’re his first true masterpiece. Short, yes (only around twelve minutes long), and, as Berg scholar Mark DeVoto has pointed out, poorly served by history. But music of tremendous invention and feeling, all the same. Check it out here:

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Alban Berg, Altenberg-Lieder, Arnold Schoenberg

[…] of Berg’s 1935 opera Lulu within its score. As composer/violinist Jonathan Blumhofer rightly notes, “The Altenberg-Lieder feature Berg at his most direct and concise, as well as his most […]