Jazz Album Review: Vince Mendoza’s “Freedom Over Everything”

By Michael Ullman

There’s a contrast here, an understandable impatience with current events placed alongside belief in MLK’s vision of the long arc of the moral universe. Neither cancels the other.

Vince Mendoza and the Czech National Symphony Orchestra: Freedom Over Everything (Modern Recordings)

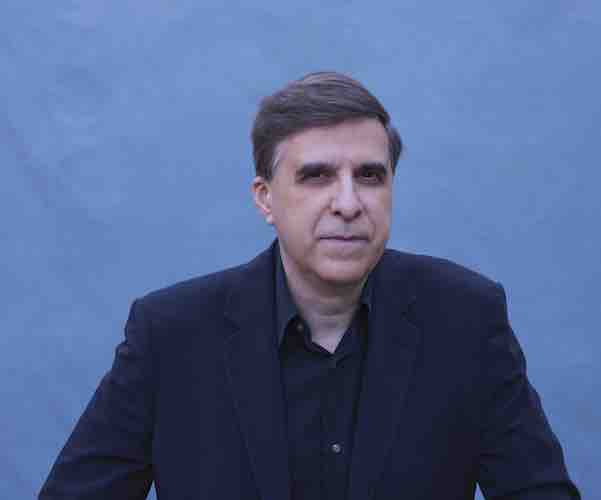

It is difficult to write about the hyper-versatile 60-year-old composer/arranger Vince Mendoza without making a long list. Among his many duties, he is the conductor of the Metropole Orkest: he has won six Grammy Awards, one for his arrangements on John Scofield’s 54, another for arrangements on Joni Mitchell’s Both Sides Now. He’s been nominated a couple dozen times. He has written for big bands and for the Turtle Island String Quartet, for the Berlin Philharmonic and for singers such as Elvis Costello, Melody Gardot, Chaka Khan, and Sting. Mendoza also wrote the music for the closing ceremony of the World Cup. He began recording in the late ’80s, a period when he played trumpet on a Peter Erskine record and synthesizer on John Abercrombie’s Animato. He’s been very, very busy ever since. More recently, he arranged singer Gregory Porter’s Nat Cole and Me and, in 2019, Fred Hersch’s Begin Again.

Mendoza’s new project is the politically oriented Freedom Over Everything, a concerto that calls for a huge orchestra: for instance, a half dozen flutes and nine French horns are listed, though I doubt all of them play at the same time. There are two additional pieces: “To the Edge of Longing,” featuring soprano Julia Bullock, and “New York Stories,” described as a “Concertino for Trumpet and Orchestra” that features trumpeter Jan Hasenöhrl.

The notes describe the main piece as “the five movement ‘Concerto for Orchestra.’” Nonetheless, the composition, as we have it here, is six movements. In its midst, Black Thought delivers a rap piece. Mendoza explains that the five-movement version was written in 2016: “There was so much discord in the country during that time. I was just so moved by the confusion, anger and entropy in this country that I wanted to make the structure of this concerto represent what was reflected in Dr. King’s quote: ‘The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice.’ I wanted the concerto to reflect that.” With its alternation between brash and brassy (even aggressive) writing and sweetly meditative movements (or moments within movements), the concerto takes the shape of a bend. But the composition’s message, and I imagine Mendoza’s earlier thoughts, are interrupted here by the rap from Black Thought: “When another man was slain, but ain’t nothin’ changed/ Cause the sad reality is, it ain’t nothin’ strange.” Thus there’s a contrast, an understandable impatience with current events placed alongside belief in MLK’s long arc. Neither cancels the other.

The concerto for orchestra begins with a bang, a military-sounding fanfare over snare drums that give way almost immediately to a questioning violin solo. The movement is called American Noise and it seems to move between two worlds. Gently wandering passages, usually featuring the strings, give way to occasional explosions of edgily repeated notes in the high strings over tympani and other thumping percussion. Around its six-minute mark some 4/4 jazzy sections arrive, a hint of the blues. Soon the guitarist introduces a swinging melody that the orchestra takes up and plays. After that witty passage, the guitar returns with what I hear as an improvised solo. “Noise” is followed by “Consolation,” with prominent parts for harp and bassoon. A simple theme is played in various textures and intensities: it sounds like a study in orchestration. “Hit the Streets” begins with a drum solo by Oleg Sokolov. The movement’s main theme is a quick-stepping scrap of melody. The orchestra never stops playing it, or at least suggesting it. The group sustains the melody even during a marimba solo, eventually overwhelming the soloist. Again, the orchestration is restless, the dynamics broadly varied.

Award-winning composer/arranger Vince Mendoza — his new recording is politically oriented. Photo: Pamela Fong.

“Meditation” follows. It is made special by its soloist, saxophonist Joshua Redman, whose gentle lyricism is soothing. Still, this is another piece that juxtaposes peacefulness with grand swells of orchestral sound … another instance of American noise. “Meditation” is followed by the dramatic, brassy “Justice and the Blues,” a composition that begins in seeming turmoil that extends over a broad sonic range (I think I hear a tuba) and then settles down into a sustained melody that is not, to these ears, particularly blues-y — until the backbeat shows up toward its end. The concerto continues with the rap “Freedom Over Everything.” Typical of Mendoza’s writing, a mild jumping-off point becomes increasingly dramatic by the time the finale is reached, suggesting a kind of reconciliation. But the possibility of the latter is questioned by the rap interlude.

That’s not all. “To the Edge of Longing,” written to a translation of a poem by Rilke, is a beautifully lyrical piece that commences with a violin solo by Alexej Rosik. The piece spotlights the shifting orchestration that I now associate with Mendoza, along with gorgeous, varied vocal writing. “New York Stories” is a piece that every classical trumpeter will want to play. Here, Jan Hasenöhrl responds nimbly to the orchestra’s lineup of lyrical and jumpy (urban) episodes.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Freedom Over Everything, Modern Recordings, Vince Mendoza