Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Film (Part Three)

Compiled by Bill Marx

Could this be a case of reviewer envy? After seeing the magazine’s music critics pay monthly homage to 1971 as a monumental year for music, the Arts Fuse‘s film critics immediately registered — en masse — their belief that 1971 was also a great year for film. And they demanded that they be given an opportunity to write about their favorites. What is an intimidated editor to do but give way to such eagerness? Below is the third effusion of enthusiasm for the best movies of that year.

I would point out from my editorial perch most of the chosen films share an urge to be provocative, particularly The Devils and Harold and Maude this time around. It all comes down to sex, death, and hysteria. This was the last gasp of the rebellious artistic/political energy generated by the ’60s. The end of the Vietnam War in 1975 quelled the era’s mounting activism — there was no more draft. Soon forgotten were Martin Luther King’s challenges to the counterculture to end racism and create a more equitable economic system. Boomers worked their proto-neoliberal asses off to consume their way to a comfortable lifestyle, culminating in the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. So it is telling that the superb films selected for this series dramatize the downside of rebellion. 1971 gave us bursts of magnificent iconoclasm that had no future — culturally or politically.

Part One of “The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Film”

Part Two of “The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Film”

— Bill Marx

Harold and Maude

Ruth Gordon and Bud Cort in Harold and Maude.

Hail 1971, a year in which a major studio release could open with a suicide-by-hanging and still be rated PG (at the time, called GP).

The hangee, who lives to stage further suicides and self-mutilations in front of his controlling mother, is lonely rich boy Harold. He meets free-spirited Maude at the funeral of someone whom neither of them knows. During the week leading up to Maude’s 80th birthday, the old lady teaches the young man to savor life, love, and sex.

Paramount Pictures’ marketing department was baffled. Harold and Maude limped through a first run, then caught fire as it was discovered at art-houses and on college campuses, becoming a cult phenomenon.

Written by Colin Higgins and directed by Hal Ashby, the film combined offbeat romance, dark humor, and potent indictments of conformity and militarism. Its challenge to the status quo reflects the optimism of the ’60s rather than the sourness that would curdle the ’70s. Songs by Cat Stevens perfectly fit the crosscurrents of whimsy and anger.

Cinematographer John Alonzo uses symmetry in an ironic way: the beauty of the milieu in which Harold has been raised is shown to be not only superficial, but suspect — a short jump to the geometrical precision of a military cemetery. The orderly mansion contrasts with Maude’s pleasingly chaotic dwelling, a former railroad car filled with a mishmash of artistic creations. Maude seeks to feed all the senses: her paintings are a feast for the eyes, her wooden sculpture for the fingers, her “odor-ifics” for the nose. All help to resuscitate the boy who’s been half-seduced by death.

One of the movie’s biggest laughs reached beyond the relationship story and into contemporary concerns. Commenting in turn on Harold’s choice for a mate are three authority figures, each with a framed portrait of his respective master: Nixon for Harold’s military-officer uncle, Freud for his psychiatrist, Pope Paul VI for his priest.

The casting was choice. Bud Cort has an embryonic quality that Robert Altman had picked up on when he made the actor his Brewster McCloud (1970). It’s impossible not to respond with empathy once Harold lets himself be vulnerable; still, losing that proto-punk talent for grand guignol almost makes you sorry to see him evolve.

Stage actress/writer Ruth Gordon’s movie career had blossomed in her 70s with startling turns in Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Where’s Poppa? (1970). The actress keeps Maude’s cartoonish excesses (“liberating” a highway cop’s motorcycle) in check, evincing a moral equilibrium that’s serious but never solemn.

Boston was a hotbed of H&M-mania, and I was there for its joyful apotheosis, when Wollaston, MA–born Gordon spoke at a screening at the Park Square Moviehouse during the summer of ’73. I still remember the crush of people on the corner of Arlington Street and St. James Avenue hoping to catch a glimpse of her — I was lucky to have gotten in for the show.

I was even able to indulge the fever during my junior year in Paris. I caught the French-language Harold and Maude stage play, starring the great Madeleine Renaud. And I was there when Bud Cort presented to the Musée du Cinéma a severed head of Harold made for a scene ultimately cut from the movie. Accepting the donation was none other than Jacques Tati — talk about a happy communing between generations.

— Betsy Sherman

Duel — The Incredible Shrinking Driver

Domesticated Mann versus death machine in Steven Spielberg’s made-for-TV movie Duel.

Some think director Steven Spielberg’s made-for-TV movie Duel says something important about his career. In it, Dennis Weaver, at the wheel of a sturdy Plymouth Valiant, turns into a fledgling Mad Max to ward off the attacks of a trucker who’s weaponized his rig into a highway murder machine. And it is true that Duel was expanded and released theatrically soon after its TV broadcast, so its cliffhanger mentality presages the coming of such Spielberg epics as Jaws, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Jurassic Park, etc.

But when Duel was made, Spielberg was just a kid with some TV under his belt. The real force behind Duel was its writer, Richard Matheson, who adapted the teleplay from his own story. Look at Duel from the perspective of Matheson’s oeuvre, and you’ll see the movie for what it is: a thematic sequel to his 1956 novel, The Shrinking Man, which Matheson adapted the following year as The Incredible Shrinking Man.

The Shrinking Man is about suburban emasculation. Its protagonist, Scott Carey, is exposed to toxins and shrinks, until the ’50s consumerist suburban dream home he’s been busting his chops to maintain transforms into a Darwinian jungle. No longer a consumer, the guy has become something to be consumed (by cats, etc.) and belittled (by his wife).

In Duel, Weaver’s character, not subtly named “Mann,” embodies an early ’70s iteration of male emasculation. Early in the film, Mann listens to news radio as he drives down some California back roads on a business trip to grovel before a client. Just before he encounters the murderous truck driver, he listens, at length, to a self-identified member of the silent majority call in to a Q&A show featuring a rep from the US Census Bureau. The guy says he doesn’t know how to fill out his census form: “I’m really not the head of the family, and yet I’m the man of the family.” The caller’s wife is at work, while he is home raising the kids, puttering around in a housecoat and slippers. Calling in is his way “just to get even with” the woman who’s the family breadwinner.

After his initial encounter with the threatening trucker, Mann stops for gas. The attendant says to Mann, “You’re the boss!” To which Mann mutters, “Not in my house, I’m not!” Mann then calls his wife and we listen as she berates him for his cowardice the night before. He was unwilling to stand up for her, to confront a guy who “tried to rape me in front of the whole party.”

What follows this castigation is Straw Dogs on the road. Mann, like Carey, must face giant, oversized threats. In both cases, these suburban schlubs embrace an over-the-top savagery. Carey confronts his nemesis, a house spider, in his basement. Mann makes a kamikaze run with his car into the truck’s grill. After embracing their inner warrior, both beleaguered males shed the demeaning smallness of their previous lives. Carey accepts that he will shrink down to the microscopic. Mann ponders the endless vista of the canyons into which he’s consigned the ruin of the crashed truck. The titular duel is not really with the killer trucker — it is with Mann’s mousey existence. Like Carey, Mann can never go back.

— Michael Marano

Two-Lane Blacktop

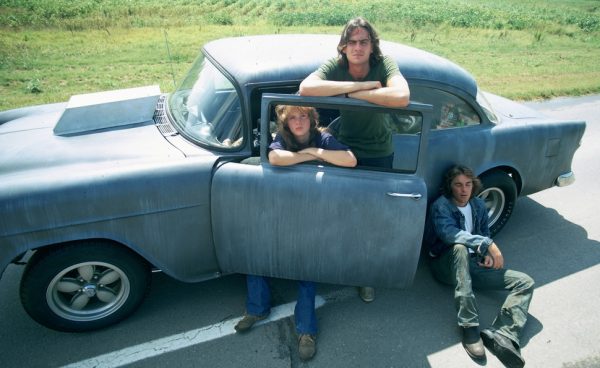

Slowly going nowhere — a scene from Two-Lane Blacktop.

Monte Hellman, who died last April at 92, left behind a body of work mostly unheralded by the general public but devoured by critics. Two-Lane Blacktop is the movie he’s remembered by, and rightfully so, because it contains a distilled version of all of the elements of his distinctive style. It could be described as a dusty New Hollywood barrenness by way of ’60s French New Wave. Essentially plotless, Blacktop follows an ensemble of nameless marginal characters as they make their way east across the USA, occasionally drag-racing for cash, sometimes chatting up the locals, always meandering, never grounded. The Driver is played by James Taylor; it was his only foray into acting (he was just about to become a huge star as a singer-songwriter). He is accompanied by The Mechanic, played by fellow musician Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys. The Girl, a young Laurie Bird, simply climbs into the back of their unattended 1955 Ford one morning, and the two men take her along, without a word exchanged, sensing a kindred spirit. Their main rival is GTO, named for his flashy new car and played by the inimitable Warren Oates (who featured in a few of Hellman’s movies). GTO challenges them to race to Washington, DC. Whoever wins takes both of the cars. But the race is quickly forgotten by all of them, and maybe by viewers as well.

Midway through the movie, Bird’s character hums the refrain of the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction” while bopping around the tables in one of the countless roadside diners they drift into. This may be the moment Hellman provides something resembling insight into his characters: they are always drifting, never quite fulfilled, always up for the thrill of another drag race. But they are never sure anything will give them what they really want, whatever that might be. It is probably unattainable — but they try.

The Girl switches cars to GTO but doesn’t stay with him long. GTO, the only big talker of the bunch, keeps peddling pipe dreams and big scores to any of the hitchhikers he picks up, but he stutters, loses his place, starts over with a new rider, and even he seems not to believe his own bullshit. The Mechanic meanwhile constantly worries over the valves and jets of their racing machine, as if he runs on anxiety. Taylor’s Driver does very little but look bored and dissatisfied, no matter if he’s racing or just staring out at the American countryside.

The film is a Bruce Springsteen song come to life, but without a rousing climax — no guitar solo or stirring vocals. Hellman refuses to romanticize or glamorize; he just lets events unfold. Those who suspect that Taylor and Wilson were just wannabe actors will be happily rewarded with portraits of subtlety and even grace. Taylor’s grimace in the final scene is for many Two-Lane Blacktop‘s lasting final image, though after that the film itself disintegrates on screen, leaving us to wonder if The Driver and company are still out there, somewhere on the road, 50 years later.

— Neil Giordano

The Devils

Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave in The Devils.

Director Ken Russell’s trippy, intense, brutal tour de force is loosely based on Aldous Huxley’s 1952 novel The Devils of Loudun, which was inspired by the true story of Father Urbain Grandier, a French Catholic priest who in 1634 was convicted of witchcraft and burned at the stake. He was accused of deviltry via reports from nuns in an Ursuline convent. Russell artfully constructs a narrative that critically examines the incident’s political intrigue, suggesting that Grandier’s persecution was motivated by the quest for power of Cardinal Richelieu, who saw Grandier’s popularity and influence as a threat.

The film opens with an elaborate theatrical production starring King Louis XIII (Graham Armitage), whose reign was characterized by persistent displays of excessive decadence. Then we see the Mother Superior of the convent, Sister Jeanne (played by Vanessa Redgrave), trying to steal a look at Grandier during a procession. The manly, handsome Oliver Reed plays Grandier, and this is among his most celebrated roles. It’s clear that Sister Jeanne is obsessed with Grandier, as are the other nuns in the convent.

Grandier is an eloquent speaker, a proud cleric, and a man whose sexual appetite (and exploits) are well known. When he visits a woman dying of the plague, her daughter becomes enamored with Grandier. The ensuing jealousy of Sister Jeanne sets in motion a chain of events — propelled by the hysteria of a full-blown witch hunt — that Russell imbues with horror and grotesque violence. The scenes of torture in this film are not for the faint of heart.

Despite its controversial content, The Devils stands out as a powerfully original vision of religious and political hypocrisy. The entire cast is first rate. Reed in particular gives a stunning performance, notable for its restraint and brevity. Look for sets designed by a very young Derek Jarman, who later went on to become one of Great Britain’s most original filmmakers. Though many fans demand that an uncensored cut of the film be released, the version available now feels solid and complete. For many, this is Russell’s most enigmatic work.

— Peg Aloi

Tagged: Betsy Sherman, Duel, Harold and Maude, Michael Marano, Neil Giordano, Peg Aloi, The Devils