Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Film (Part One)

Compiled by Bill Marx

Could this be a case of reviewer envy? After seeing the magazine’s music critics pay monthly homage to 1971 as a monumental year for music, the Arts Fuse‘s film critics immediately registered — en masse — their belief that 1971 was also a great year for film. And they demanded that they be given an opportunity to write about their favorites. What is an intimidated editor to do but give way to such enthusiasm? And to agree with what Nicole Veneto says about her pick — that after five decades the movies written about below (and those to come, including McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Devils, Walkabout, and Dirty Harry) still have a lot to offer to young people. If you like your films “weird, sexually provocative, and intellectually stimulating” (add violence to the mix) then our critics will feed your appetite splendidly.

I would point out from my editorial perch that the word provocative is key when looking at the movies of that year. This was the last gasp of the rebellious artistic/political energy of the ’60s. The end of Vietnam quelled the era’s mounting activism — there was no more draft. Martin Luther King’s challenges to the counterculture to end racism and create a more equitable economic system were forgotten as Boomers worked their proto-neoliberal asses off to consume their way to a comfortable lifestyle, culminating in the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. It is telling that the lineup of superb films below are about the end of rebellion — not its rejuvenation. 1971 gave us bursts of magnificent iconoclasm that had no future — culturally or politically.

Part Two of “The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Film.”

— Bill Marx

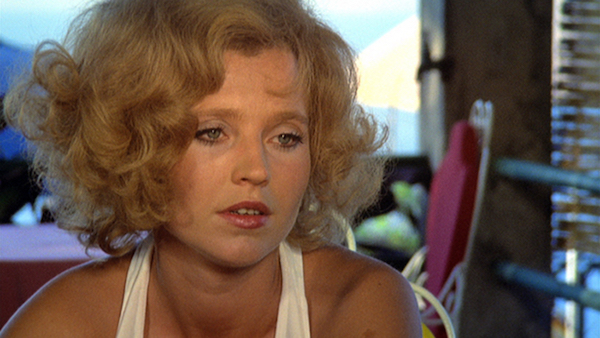

The lovely Hanna Schygulla in Beware of a Holy Whore.

Beware of a Holy Whore

With a career that boasted over 40 films, theater productions, and the celebrated 15.5 hour television miniseries Berlin Alexanderplatz, director Rainer Werner Fassbinder worked himself into an early grave, dying at the age of 37 from a drug overdose. “What I would like is to make Hollywood movies,” Fassbinder said. “That is, movies as wonderful and universal, but at the same time not as hypocritical.” One of his movies that channeled Tinsel Town backstabbing with the requisite flair is his autobiographical 1971 film, Beware of a Holy Whore.

The story was inspired by Fassbinder’s own experiences filming his spaghetti western, Whity. A German film crew is stuck in a Spanish hotel with no film, no script, a jukebox, and a bottomless supply of Cuba libres. No footage is shot until the end of the narrative; the first 90 minutes are completely devoted to chronicling the abrasive relationship between filmmaker Jeff (played by Lou Castel decked out in a leather jacket that recalls Fassbinder’s trademark ensemble) and his crew. Fassbinder appears as a wired version of himself; he plays a production manager who savors the little power he has left by screaming at crew members and hotel staff.

Jeff promises marriage and children to several actresses before his temper tantrums leave the women in tears or stunned by one of Jeff’s backhands to the face. As if that weren’t enough, Jeff stews the emotional pot with a sexual relationship with his leading man, Ricky (Marquard Bohm). The only seasoned actor on set, Eddie Constantine, plays a satirical version of himself, continually questioning the validity of Jeff’s filmmaking decisions. The vision of visceral group masochism was intended; it was part and parcel of Fassbinder’s wish to bring the rawness of the Antiteater — the avant-garde stage troupe he co-founded in the late ’60s — from the stage to the cinema. Ironically, Beware of a Holy Whore would be the film that upended his connection with Antiteater.

A white-suited Rainer Werner Fassbinder in a scene from his Beware of a Holy Whore.

Beyond the hybrid mix of lush and acrylic backdrops shot with the graceful eye of cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, the film’s soundtrack adds a racy rhythm to the story’s drunken melodrama and dark comedy. Songs like Leonard Cohen’s “That’s No Way to Say Goodbye” and Spooky Tooth’s “I’ve Got Enough Heartaches” accentuate the boredom-driven hostility and bacchanal. There is a cyclical precision to the decadence, such as when the depressed set designer (Kurt Raab) is about to return to his room before being ushered back to the bar to continue drowning (publicly) in his self-pity.

Despite its minimal critical reception at the 1971 Venice Film Festival, Beware of a Holy Whore signaled a shift in Fassbinder’s oeuvre. Hereafter he would be influenced by the “women’s pictures” of Douglas Sirk when crafting his sharp critiques of race and sexuality, such as the internationally admired Ali: Fear Eats His Soul and The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant. As for Beware of a Holy Whore, Bob Dylan was a fan; he screened it, along with Marcel Carné’s Children of Paradise, for his band during his 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue Tour. In 2006, Martin Scorsese recalled Dylan coming up to him after filming The Last Waltz and telling him to watch Beware of a Holy Whore.

“I don’t throw bombs, I make films,” quipped Fassbinder. In the case of Beware of a Holy Whore, the director blew up his own ego before he retreated to modeling his work on the domestic American dramas he savored in his youth.

— David Stewart

Three Pictures from a Revolution: Sweetback’s Baadaaas Song, Straw Dogs, and Punishment Park

Melvin Van Peebles in his film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadaaas Song.

In 1971, Melvin Van Peebles Sweet Sweetback’s Baadaaas Song was a revolutionary act of guerilla moviemaking: the indie film was underexposed, riddled with jump cuts and poorly dubbed dialogue, filled with shaky handheld shots, and driven by a plot that hung together by a thread. But it worked: this $500,000 film grossed $15 million. Its images of sexual bravura and violence against police brutality and corruption scored with viewers who were excited by “a take no prisoners political manifesto.” The film drew a Black audience hungry for strong, honest representation. In the past, as the director explained in his documentary Classified X, “the colored folk [in film] were always quaking and ‘yassa bossin’ and shufflin’” and that bore no resemblance to “the majestic, hard working folk struttin’ around the south side of Chicago where I came from.”

The Black Panthers made it required viewing for members. For me, the politics of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing and the lunatic style of Boots Riley’s Sorry To Bother You both tap into the spirit of Van Peebles’s film. Shaft, which followed Sweetback that year, featured a macho Black hero and the Blaxploitation movement was born. “Hollywood took my formula,” laments Van Peebles, “reduced the concept of negritude to a flamboyant cartoon and reversed the political message, turning it into a counter-revolutionary one.” The freedom and daring of Sweetback’s Baadaaas Song remains a threat to the staid film establishment.

Rebel Hollywood director Sam Peckinpah offered up a different challenge. The graphic violence of his masterful western epic The Wild Bunch deromanticized the western (and critiqued the Vietnam War) by way of its aging antiheroes, graphic violence, and nihilistic ending. In Straw Dogs, he brought a Neanderthal interpretation of male/female relationships into the present. Years earlier, Dustin Hoffman had epitomized youthful alienation in The Graduate. Now he was cast as a mathematician or, in Spiro Agnew’s disparaging words, an “effete intellectual snob.” His wife, played by steamy sex kitten Susan George, at first relishes the attention of the slobbering lads working on the couple’s roof in Cornwall, England. She does not submit to their advances unwillingly. Eventually, she is raped. To save his wife and his manhood (and protect a feeble-minded worker), Hoffman’s egghead becomes a he-man and slaughters the couple’s tormentors.

Critic Pauline Kael called Straw Dogs “a fascist work of art.” Peckinpah claimed he was just doing the job he had been assigned, adapting what he called a “rotten book” (The Siege of Trencher’s Farm) to the screen. Did Peckinpah imagine his film would pull Baby Boomers out of the warm womb of hippie self-satisfaction with a stinging slap on the ass? Or did he really believe that retribution through violence would lead to real manhood and winning fair maid? Whatever his intention, Straw Dogs remains an exhilarating entertainment — as well as a bucket of cold water in the face of the peace and love generation.

A scene from Peter Watkins’s Punishment Park.

British director Peter Watkins offered a very different kind of cinematic provocation. Punishment Park is an early agit-prop pseudo-documentary. Allegedly shot by “international television crews,” the film documents a group of young protesters brought before an ad hoc government committee and tried for “subversion.” In lieu of prison sentences, they are given the option of choosing to try to cross Punishment Park, an expanse of open desert, with police and National Guardsman in hot pursuit. If the dissidents make it to the finish line without being caught or shot, they will be freed. The film cuts between the court proceedings and escape attempts. An officious narrator explains:

Punishment Park: described by the US senate subcommittee on Law and Order as a necessary training for law officers and the National Guard in the control of those elements who seek the violent overthrow of the United States government and a means of providing a punitive deterrent for said subversive elements.

Watkins uses the angry speeches of the defendants to air radical feminist, racial, and antiwar sentiments. Handcuffed to their chairs (an echo of Bobby Seale’s being bound and gagged in the courtroom during the Chicago 7 trial), the protesters are continually interrupted, their speeches unceremoniously shut down. The “footage” of young prisoners attempting to cross the desert — hampered by the vicious tactics of police — recall news coverage of the protests of the ’60s. Watkins rejects Direct cinema in order to create a jarringly real experience through the adroit use of somber narration, jerky handheld camera shots, ambient sound, and constant zooms. More than once, following a screening of the film in a faux documentary class I was teaching at a college, a foreign student would ask: “This is fake, right? It isn’t real is it?”

Fifty years later we’re still asking that question.

— Tim Jackson

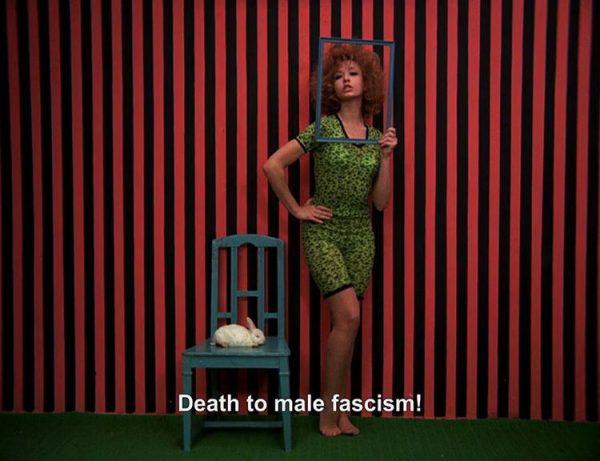

A scene from Dušan Makavejev’s W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism.

W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism (Yugoslavia, West Germany, Serbia)

On day two of the quarantine lockdown, I impulsively bought a yearlong subscription to The Criterion Channel, and for once in my life I didn’t cancel before the free trial ended. The streaming platform offered me the opportunity to become enamored of the surreally anarchistic delights of New Wave cinema from the former Eastern Bloc — Czechoslovakia, Poland, Serbia, and Yugoslavia specifically. In Yugoslavia, this period of openly confrontational and experimental filmmaking is known as the Black Wave (a reference to its use of dark humor to critique Soviet Yugoslavian society). Arguably the most famous contributor to the movement was Serbian director Dušan Makavejev. Before shocking the world with 1974’s Sweet Movie, he was effectively exiled from Yugoslavia and expelled from the communist party because of his 1971 film W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism. Withheld from release by the former Soviet nation for 16 years, W.R. is an experimental, mixed-genre cine-collage of (unsimulated) sex and satirical socialism, framed through the controversial theories and practices of Freud protégé Wilhelm Reich. The idea was to examine the inseparability of revolutionary, progressive politics, and sexual liberation on both sides of the Iron Curtain. W.R. mixes cinéma vérité documentary filmmaking with an avant-garde sex comedy, resulting in a film that plays like a sex education video produced by Andy Warhol’s Factory.

The film is very much a time capsule that packages late-’60s counterculture and Cold War sexual politics, but I believe W.R. has as much to offer young audiences today as it did for my parent’s generation. The New York sections that follow genderqueer Warhol Superstar Jackie Curtis exemplify Reich’s (then radical) theories on sex and gender, which are strikingly prescient of third-/fourth-wave feminism’s reevaluation of sexuality and gender as distinct and fluid identities. In one interview, Curtis, her eyes smeared with glitter, speaks with remarkable frankness about her own sexual experiences. She also talks about being rejected by a former male lover after she transitioned, despite the fact that “I was the same person, I’m literally the same person.” Curtis is hardly the most eccentric element in an art-house film featuring plaster cast penis molds and ice skate decapitations, but upon rewatch, her presence adds an indispensable humanity to Makavejev’s cinematic sexual manifesto. So if you’re like me and you enjoy your movies weird, sexually provocative, and intellectually stimulating, W.R. is essential viewing.

— Nicole Veneto