Television Review: “Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell” — Avoiding the Ugly Side of the Tale

By Sarah Osman

Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell does a solid job of introducing someone new to Biggie’s work and establishing his enormous influence on hip hop.

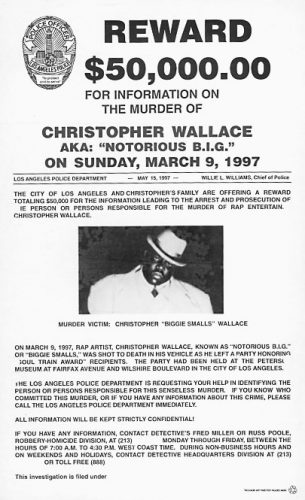

I believe that you can tell a lot about a person based on whether they prefer Biggie or Tupac. As a native of Los Angeles, I do tend to lean toward Tupac, but I can’t deny Notorious B.I.G.’s giant talent and what he did for hip-hop and New York. I’ve always found Biggie’s lyrics to be rather poetic and his vision expansive: his rhymes are far more complex than previous rappers, and his music fuses multiple genres. I still tear up a bit thinking about Biggie’s murder. I can’t help but dream about how he would have developed as a musician. But Biggie’s life was tragically taken from him at 24 when he was murdered in a drive-by shooting.

I believe that you can tell a lot about a person based on whether they prefer Biggie or Tupac. As a native of Los Angeles, I do tend to lean toward Tupac, but I can’t deny Notorious B.I.G.’s giant talent and what he did for hip-hop and New York. I’ve always found Biggie’s lyrics to be rather poetic and his vision expansive: his rhymes are far more complex than previous rappers, and his music fuses multiple genres. I still tear up a bit thinking about Biggie’s murder. I can’t help but dream about how he would have developed as a musician. But Biggie’s life was tragically taken from him at 24 when he was murdered in a drive-by shooting.

Netflix’s latest documentary, Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell, focuses on “Big Poppa,” and it presents an intimate look at the legendary rapper’s life and career. Produced by his mother and Sean Combs, Biggie is pretty much a hagiography, glossing over any unattractive parts of his past. The documentary’s opening is quite interesting — we learn about the childhood and early years of Christopher Wallace. His mother, Voletta, was a tenacious immigrant from Jamaica who worked hard and went to school in order to become a teacher. Hers is a conventional immigrant story; she wanted to provide Wallace with a better life. Voletta turns out to be a bit of a character as she recounts some of her concerns around Wallace’s career choice (her shock over the amount of profanity in his music is quite funny). But it’s also easy to see how her determination inspired him. Every summer, Voletta took her son back to Jamaica, where he was introduced to reggae and jazz. We are introduced to Wallace’s childhood friends, particularly Donald Harrison, a neighbor who was a respected jazz musician. Under his tutelage, Wallace was introduced to jazz and, as Harrison explains, many of Biggie’s songs could be played to the rhythm of a bebop drum solo. It’s a startling tidbit that illuminates a facet of the performer’s creative genius.

The film doesn’t gloss over Biggie’s bleak past — he hustled crack on a street corner in Brooklyn — but it doesn’t detail much about it either. The film progresses quickly from mentioning Biggie’s time as a crack dealer to his being noticed by Sean Combs and then working with him. This isn’t all that surprising considering Combs was one of the producers of the film. But this meant that the emphasis was going to be placed on his and Biggie’s collaborations. Which means there are some major gaps in the story. Still, it’s fun to see Biggie, early on, take control of the mic at street-corner rap battles — it’s awe inspiring to see just how confident, smooth, and in control he was as an MC.

Interspersed in between interviews is (for lack of a better term) “home video footage” of Biggie and his crew out on tour. Shot mostly by his childhood friend Damion “D Roc” Butler, these short snippets come off as early versions of TikTok. D Roc recorded everything, from Biggie commanding a crowd and laughing at groupies wanting to sleep with him to his and his crew’s curiosity about the world outside of New York City. For Biggie fans, it feels as though you are watching the home movies of a close friend.

Unfortunately, the documentary falls short when it completely glosses over the second half of Biggie’s life, particularly his various feuds with West Coast rappers. Although she is interviewed, we are given little background about Biggie’s wife, Faith Evans, who was a strong artist in her own right and had a child with him. Suge Knight, who did for West Coast rap what Combs did for East Coast rap, is barely mentioned — despite the key role he played in the ’90s hip-hop turf wars. This is particularly jarring considering all the rumors surrounding Knight, many focusing on his criminal behavior (Knight is currently incarcerated and is rumored to have killed not only Tupac, but also Biggie). And the biggest feud of all — the rivalry between Biggie and Tupac — is only brought up in the last 20 minutes. We learn very little about Tupac, beyond the fact that he was the West Coast equivalent of Biggie, had some problems with him, and was also tragically shot at a young age. Considering that, even now, hip-hop fans vociferously argue over which rapper was better, the Biggie vs. Tupac controversy obviously warranted much more attention.

Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell does a solid job of introducing someone to Biggie’s work and establishing his enormous influence on hip-hop. I hope that the film will introduce younger audiences to Biggie and help keep his legacy alive. But there is just not enough here to intrigue Biggie fans; there is a reluctance to deal with his career and personal life in depth. Perhaps more years will have to pass before the artist’s darker side will be exposed. Still, for the moment, Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell reminds us of why he remains one of the greatest names in hip-hop and why we still continue to blast his music.

Sarah Mina Osman is a writer living in Los Angeles. She has written for Young Hollywood and High Voltage Magazine. She will be featured in the upcoming anthology Fury: Women’s Lived Experiences under the Trump Era.

Tagged: Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell, Netflix, notorious B.I.G., Sarah Osman