Book Review: “Rocking the Closet” — Queering the Mainstream

By Adam Ellsworth

Audiences knew (or at least thought they knew) something was up, and that something was what made these performers unique.

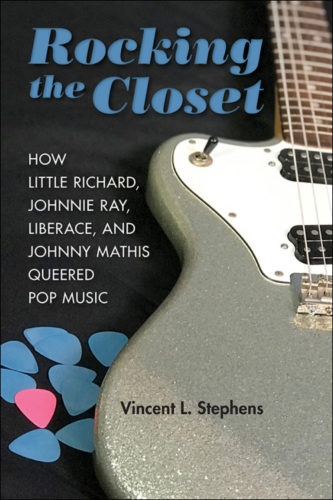

Rocking the Closet: How Little Richard, Johnnie Ray, Liberace, and Johnny Mathis Queered Pop Music by Vincent L. Stephens. University of Illinois Press, 248 pages, $27.95 (paper).

The 1950s are typically remembered as a time of white picket fences, the supremacy of the “traditional” nuclear family, and no boat-rocking. Sure there was dissent and “alternative lifestyles,” but people involved in those kinds of things were members of a subculture.They weren’t in the mainstream.

This is all true enough if we’re painting with a wide brush, but as Vincent L. Stephens makes clear in his well-argued and thoughtful new book Rocking the Closet, when it came to popular music, even the mainstream wasn’t quite as “straight” as we normally remember it.

The four men listed in Rocking the Closet’s subtitle — dubbed the Queer Quartet by Stephens — were all major mainstream stars in the ’50s. The book argues that their popularity was not in spite of, but because of, the way they all “queered” expectations of what was acceptable behavior for men in postwar America. Audiences wanted something different, something that wasn’t square, which especially helped Ray and Little Richard. Not that any of these men were “out” during their years of peak popularity. That would have risked taking things too far. But audiences knew (or at least thought they knew) something was up, and that something was what made these performers unique.

Whatever people thought they knew about the Queer Quartet, an application of “don’t ask, don’t tell” propped up the audience/performer relationship (especially during the decades-long career of Liberace). Part of not telling meant the Quartet needed to employ various tools from what Stephens calls the Queering Toolkit to be able to queer the mainstream without actually admitting they were sexually queer.

For Johnnie Ray—a post-crooner, pre–rock and roll singer described in Rocking the Closet as “deaf, effeminate, bisexual, openly approving of black culture, and loathed by many music critics”—this meant playing on his “freak” status, which made him seem more vulnerable (and therefore attractive) to many of his fans. (He would become overwhelmed by emotion during his performances.) It also made him appear as more of a curiosity (“Look at the freak!”) than a threatening sexual deviant. Unfortunately for Ray, he was hounded by tabloids (a fate also suffered by Liberace), which were only too willing to speculate on his sexuality, while also reporting on the singer’s real arrests for homosexual solicitation. As a response to tabloid coverage, which also built on an initial fear that audiences wouldn’t accept anybody who wasn’t sufficiently heteronormative, Ray used another tool from the Queering Toolkit: self-domestication. This meant that after his initial success he steered his musical career to the middle of the road and played up his desire for marriage and a family. In 1952, he even got married. (It’s worth noting that while this marriage is now understood as being arranged for publicity, Ray did have unpublicized affairs with women throughout his career, so his sexual interest in the opposite sex was not solely for promotional purposes.) When we consider how much popular music audiences of the ’50s liked having their expectations queered, it’s not surprising that Ray’s career didn’t survive his self-domestication. His fans didn’t care about the tabloid coverage, but they did care about his turn to bland pop. As Stephens writes, “His audience did not abandon him because he was ‘queer,’ he did.”

Stephens also notes that rock and roll pioneer Little Richard also used the tools of “self-enfreakment” and “domestication.” And as with Ray, fans much preferred the freak. Throughout his career, the self-appointed “bronze Liberace” went back and forth from gender-bending wild man to God-fearing, capital-H Heterosexual before finally settling (in the ’80s) on a version of himself that blended both of these sides. Unlike the Caucasian Ray, Little Richard also needed to use a different tool from the toolkit: he had to “play the race card.” Stephens shares two quotes from the African American Richard that sum up how he did this:

By wearing this make-up I could work and play white clubs and the white people didn’t mind the white girls screaming over me. I wasn’t a threat when they saw the eyelashes and the make-up. They was willing to accept me too, cause they figured I wouldn’t be no harm.

We were breaking the racial barrier. The white kids had to hide my records cos [sic] they daren’t let their parents know they had them in the house. We decided that my image should be crazy and way-out so that the adults would think I was harmless.

Basically, Richard argues that white America let him slip into the mainstream because he wasn’t seen as a militant black man who was going to knock up their daughters. Once they let him in though, good golly did he rip the place up.

Little Richard. — the self-appointed “bronze Liberace.” Wiki Common.

Stephens is careful not to shame or condemn any member of the Quartet’s decision to self-domesticate, or to not come out as gay or bisexual during their commercial peaks (or in the case of Liberace, at all). This empathy acknowledges a powerful reality: such decisions are always complicated, and they were especially complicated in the mid-20th century.

Take Stephens’s following passage about pianist and all-out showman Liberace, which defends him for never coming out as gay, even when he was dying of AIDS in the ’80s:

What his critics have not asked is why his [Liberace’s] sexual orientation had to be the most salient part of his identity. Arguably, he did more to push boundaries by existing in a glass closet than he might have if he had taken a more overtly liberated stance. This was not exactly a model available to him in terms of risks or benefits. He had a national career for twenty years before an organized political movement arose around the act of coming out and visibility politics. He also expended a lot of time and resources defending himself in court [against tabloid reports about his sexuality] and would have appeared highly hypocritical.

Liberace may have never come out as gay, but he didn’t exactly tone down his appearance or personality. Early in his career, he “shocked” the classical music world by wearing a white tuxedo. As his career progressed, he performed covered in sequins, rhinestones, and jewels. Outrageous as Liberace liked to look, Rocking the Closet notes that in his final years, he did turn to two specific tools in the Queering Toolkit to control the narrative about his life and illness as he “self-neutered” and “counter-domesticated.” When a former lover sued for palimony, Liberace denied everything. The fact that this lover had also been part of Liberace’s stage act made it easier for him and his lawyers to paint the man as nothing more than a disgruntled former employee. After all, how could this male employee have been a lover of Liberace’s when Liberace didn’t have sexual relationships with men? This was the facade the performer kept up right until the end. When he died of AIDS in 1987, his publicist said the cause of death was heart failure.

Author Vincent L. Stephens.

Not every member of the Quartet kept his sexuality a lifelong secret. Johnny Mathis spoke openly about his sexuality to Us Weekly in 1982, and then again to CBS Sunday Morning in 2017. During his commercial peak, though, he was not able to be so forthright. Like the rest of the Quartet, he went to the toolkit and employed various strategies during his career, including self-neutering. He simply didn’t talk much about marriage, having children, or his romantic life at all. He didn’t draw any controversy to himself so, while people had their assumptions about Mathis’s private life, nobody asked too many questions. Compared to the other performers examined in Rocking the Closet, Mathis was the most under-the-radar, which is perhaps why his dandy style allowed him to appeal to both women (who may or may not have suspected anything) and other gay men (who suspected correctly).

Rocking the Closet concludes with very brief looks at three modern performers who used the Queering Toolkit to great success: Michael Jackson, Prince, and Clay Aiken. It would have been interesting had Stephens expanded this section, and drawn more direct comparisons between Ray, Little Richard, Liberace, and Mathis and more of those that followed in their footsteps. Nevertheless, the ending is saved by the inclusion of the hyper-heterosexual Prince. In doing so, Stephens makes it clear that while the Quartet that are the book’s focus were all bisexual or gay, anybody can “queer” music and the culture at large, no matter who they share a bed with. Regardless of the decade, when popular music gets queered, it also gets a hell of a lot more interesting.

Adam Ellsworth is a writer, journalist, and amateur professional rock and roll historian. His writing on rock music has appeared on the websites YNE Magazine, KevChino.com, Online Music Reviews, and Metronome Review. His non-rock writing has appeared in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, on Wakefield Patch, and elsewhere. Adam has an MS in journalism from Boston University and a BA in literature from American University. He grew up in Western Massachusetts, and currently lives with his wife in a suburb of Boston. You can follow Adam on Twitter @adamlz24.

Tagged: Adam Ellsworth, Johnnie Ray, Johnny Mathis, Liberace, Little Richard, Rocking the Closet

Looking forward to reading this book. As a young college student in the mid-1960s, I was “in love” with Johnny Mathis and his music. So were a number of my girlfriends. He was at the height of his popularity when we attended one of his concerts in a Cherry Hill, NJ nightclub. And as young female music fans often do, we followed Mathis and his entourage back to the motel where they were staying, hoping that — “chances are” – we’d be invited in for some post-concert frivolity or at least nab an autograph. All hopes were dashed when one of his minions appeared on the balcony, looked down on our motley crew assembled in the parking lot and said, “Sorry, girls, he doesn’t swing that way.” Downtrodden, we headed back to campus, crushed but a little wiser, too, about the ways of the world.