Theater Review: “Indecent” — A Dangerous World for People of Faith

By Robert Israel

Indecent is a play of contrasts: piety versus blasphemy, joy versus heartbreak.

Indecent by Paula Vogel. Directed by Rebecca Taichman. A co-production between the Center Theatre Group and the Huntington Theatre Company at the Huntington Avenue Theatre, 264 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA, through May 25.

Lisa Gutkin and Elizabeth A. Davis in the Huntington Theatre Company production of “Indecent.” Photo: T Charles Erickson

Seated onstage as the audience enters the Huntington auditorium are ten men and women, some holding instruments, some wearing fedoras, all of them dressed in somber clothes that fit like sacks on their bodies. These ten figures comprise a minyan, or quorum, required by Jewish law before a worship service can begin.

But tonight’s performance is not about only about worship. Yes, it draws on the teachings of the Jewish faith, but it goes beyond the Five Books of Moses. It is a play of contrasts: piety versus blasphemy, joy versus heartbreak. Set in Europe and America in the 20th century, this “true story of a little Jewish play” tells of cultural triumphs ultimately snuffed out by the Holocaust.

This play finds dramatist Paula Vogel is at her most ambitious. She stitches the play’s threads into a finely woven production that weighs in just under two hours without intermission. A talented cast and an astute director support her efforts. Nary a moment is wasted.

This long, one-act drama also breathes new life into the once-thriving Yiddish theater. By presenting scenes from an early 20th century Yiddish play, The God of Venegence, by Polish playwright Sholem Asch, we are reintroduced to this theatrical genre by learning of a play that once enjoyed successful runs throughout Europe and Russia before making its New York premiere — where it was summarily banned — in 1923. Vogel explores how Asch’s play fits into the canon of literary works produced from this turbulent era, namely plays by Eugene O’Neill (and suggested, but not mentioned, the literary works by James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and others, who tackled, using unexpurgated language, themes of human sexuality, among other topics).

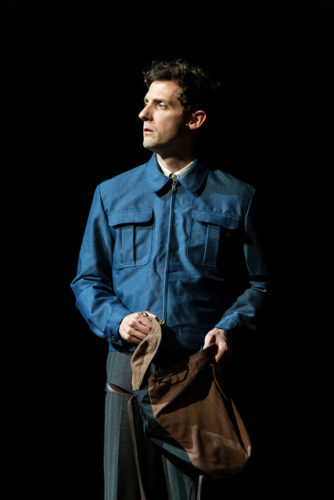

Joby Earle in the Huntington Theatre Company production of “Indecent.” Photo: T Charles Erickson

Playwright Asch had the temerity to write about the dark side human sexuality — prostitution and lesbianism — during a time when published Yiddish works were at their zenith renaissance, exemplified by writers like I.L.Peretz who considered themselves beacons of the word. During a scene in Peretz’s salon, Asch’s work is read aloud. Some proclaim that it is brilliant, “it changed my life,” says one character. “It shows women as flesh and blood,” proclaims another. Yet others protest. “It is Jewish anti-Semitism,” several object. Vogel uses contrasting scenes to show the hazardous chasm between the sacred and profane, grappling with what should be allowed in the temple versus what remain outside its gates.

The play is helped mightily by the music and dancing, although a device to indicate transitions between scenes – a female cast member, arms raised, twirling like a ballerina – is overused. We follow superscripts projected on the Huntington’s back wall (in Yiddish and English) that alert us to transitions, so the device of a Whirling Dervish becomes a bit much.

The play is also a love story between two women. There are tender scenes of two females embracing and kissing, a first for Broadway in the 1920s and one of the reasons The God of Venegence was shut down. I was reminded of the works by Yiddish novelist and Nobel laureate Issac Bashevis Singer – whose name is strangely absent from the constant name dropping of other authors throughout the play – who wrote, often controversially, about the theme of sexuality.

But that point, as we say in Yiddish, is schmitzick, or minor at best. This play is so tautly wound that we are pulled in from first scene to last, culminating in a final image — an outpouring of passion and chaos between two women in the rain. The world these characters inhabit — the world we live in — is a dangerous one for people of faith, whether they are devout or practice their faith on the periphery. By stubbornly clinging to our faith we hold onto our humanity, and that, finally, is Vogel’s triumphant message.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel, and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.