Jazz Review: Second Dispatch from the 39th Montréal Jazz Festival

One of the most astonishing sets of my week in Montréal featured two Frenchmen, accordionist Vincent Peirani and soprano saxophonist Émile Parisien.

The Dr. Lonnie Smith Trio at Gésu. Photo: Victor Diaz Lamich.

By Michael Ullman

First Dispatch from the Montreal Jazz Festival

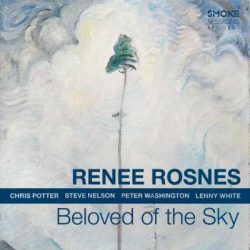

My Montréal International Jazz Festival experience resumed at Le Festival à la Maison symphonique. Running from one concert to another, I caught the second half of the July 4th set with pianist Renee Rosnes and vibist Steve Nelson. She’s an admirable musician with a fascinating breadth of interests that is reflected in her recordings, which include versions of tunes by Ornette Coleman, the Beatles, Strayhorn, Monk, Miles, and Fats Waller. She can even play ballads with a dexterous combination of grace and force. Some of her discs, such as Beloved of the Sky, feature Nelson and saxophonist Chris Potter. Her Life on Earth explores environmental themes, as does the number they played in Montreal — Rosnes’ “Galapogas.”

Rosnes was followed by an all-star trio — Dave Holland, Chris Potter, and Zakir Hussain — that interrupted its European tour to play at the Festival. One hears again and again from musicians that this mega-gathering is a favorite annual stop. (I heard several say they dreamed of playing the Montreal Jazz Festival before they finally got an invite.) Before the concert began, tabla player Hussain was presented with an award that celebrated his contributions to world music. Graciously, Hussain gave thanks for the musical enlightenment he had received in his career from such masters as bassist Holland.

The trio opened with Holland’s rhythmically complex tune “Lucky Seven.” (He’s recorded it with Nelson and Potter on Critical Mass .) Holland first came to the attention of most Americans, including my teenaged self, when Miles Davis brought him in to replace Ron Carter. It was a difficult situation: I remember my own astonishment at seeing a blondish, bearded Englishman rather than Carter. He won me and (probably) every other serious listener over with his magnificent tone, agility, daring, and ability to follow Miles, and later Chick Corea, virtually anywhere they wanted to go — while he still anchored the band. Much later, I heard him give a solo concert at Jordan Hall in which he miraculously recreated Charles Mingus’s “Haitian Fight Song,” a wailing ensemble piece that Mingus said evoked racial strife. Still later, at the same venue, Holland and Potter played a similarly incandescent duet set.

Potter has been making his mark as a musician since he was in high school in Columbia, South Carolina. He’s the saxophonist’s saxophonist. I sat with Potter in between sets once, and watched as one sax player after another came to pay him shy tribute. He’s a master technician who uses the entire range of the horn with ease and passion — and always with a beautifully rich tone. He’s played everywhere and with almost all the best. What struck this listener about the trio was the beautiful tone of each instrument, and the subtlety of the players’ interactions. It’s a perfect small group: each of the musicians listens and reacts to each other, but then express themselves with compelling individuality in extended solo opportunities. Potter seemed to be paying tribute to Sonny Rollins in his tunes “Island Feeling” and “Good Hope.”

The next night at 6 p.m. I found Potter again, this time at the converted chapel that they call Gésu as a guest of the Dr. Lonnie Smith Trio. The bearded, be-turbaned Smith has been playing a combination of ethereal funk and meditative musics for half a century. For a while, he was a favorite in the smooth jazz (I am tempted to call it soft jazz) world. His approach was also briefly called acid jazz. He told the crowd that his “music is a reflection of what’s happening at the time..The organ is like the sunlight, rain and thunder…it’s all worldly sounds to me.” With Potter aboard, the music was certainly worldy — and impassioned. The band opened with “Mellow Mood” from Smith’s record Spiral. It kicked off with the leader exploring a deep rumble in the organ, but then the piece erupted, with funky drumming sometimes dominating the stage, as did Potter’s solo. The saxophonist was delicate the night before; here Potter reveled in the raucousness, occasionally shrieking (in tune of course), honking, but just as often rushing up and over the entire range of the horn in breathtaking fashion. The band followed with a blues, and then an unannounced ballad, when I really wished for more subtlety from the drummer.

I heard that nuance from percussionists later, but first I encountered one of the most astonishing sets of my week in Montréal. It featured two Frenchmen, accordionist Vincent Peirani and soprano saxophonist Émile Parisien. In their set, besides a few originals, they played some numbers made famous by saxophonist Sidney Bechet, though I am not sure he would have recognized them. Parisien began his solo on “Song of Medina (Casbah)” by playing almost out of the side of his mouth, providing a pure, sweet tone. Peirani evoked a low groaning tone from his accordion — one of the many sounds I have never heard before from that instrument. Soon the saxophonist was hopping about the stage in an increasingly passionate solo that exuded a songfulness worthy of Bechet. Peirani followed with a low, stuttering, and repeated chord. It’s as if he had decided to go into hiding. But, when he emerged, Parisien supplied a series of bright chords and impossibly swift lines. They followed with a tribute to the avant-garde French clarinetist, Michel Portal. Elsewhere. the pair displayed a nimble sense of humor, generating an easy rapport with the audience, particularly when they came up with several fake endings, and then reproved us for applauding prematurely. I am not sure what musical field these two play in, but they are giants.

Finally (for me) pianist Steve Kuhn came on stage, celebrating his 80th birthday with a set that included bassist Adrian O’Donnell and drummer Billy Drummond. After the slam bang drums in Lonnie Smith’s set, I was drawn immediately to the modulated but still driving efforts this veteran drummer. On “In a Sentimental Mood,” Drummond played through the first chorus by poking at the cymbals with his fingers. At the beginning of the bridge, when he used his soft mallet, it was a major event. He wasn’t just soft, or always quiet, but he was consistently thoughtful and instantaneously responsive. Every time he complicated the rhythm it seemed to be a logical extension of Kuhn’s solo. The pianist remains a master, whether he’s performing a blues tune (with adapted changes), a bit of Debussy’s “La plus que lente” (it segued into “Passion Flower”), Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation,” or Kuhn’s own medley of “Trance/ Oceans in the Sky.” He began and ended every set with his standard note of gratitude: “Thanks for coming out to support this music to which we have devoted our lives.” With their wild applause, audience members thanked Kuhn for creating the music to which we are devoted.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.)

Tagged: Billy Drummond, Chris Potter, Dave Holland, Émile Parisien, Montreal Jazz Festival, Renee Rosnes, Steve Kuhn, Vincent Peirani