Fuse Film Preview: Graham Greene’s “Words in Motion” at the MFA

In his best screenplays, Graham Greene explored the idea of the protagonist as anti-hero well before it became a popular trope in the 1950s and ’60s.

Words in Motion: Graham Greene as Screenwriter, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, January 2 through 17.

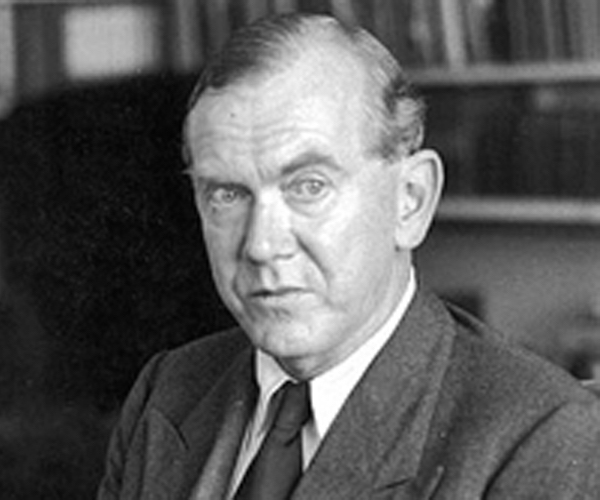

Graham Greene the screenwriter: “The great advantage of being a writer is that you can spy on people. You’re there, listening to every word, but part of you is observing.”

By Paul Dervis

Well, the Museum of Fine Arts has come up with another sterling start of the year retrospective. Last January, they showcased several films of Alec Guinness and it was thrilling. This time around they are screening five films made from screenplays by novelist Graham Greene: four of the films are well known, the fifth is a rarely shown gem. Yes, the famous quartet are shown fairly frequently on movie channels, but this is an opportunity to see them on a big screen, the way they were supposed to be viewed.

The opening day of Words in Motion includes Greene’s most famous film, The Third Man. This classic thriller, set in Vienna just after the end of World War II, is generally ranked as director Carol Reed’s masterpiece. The divided city makes for a darkly mysterious backdrop, and Orson Welles gives his best performance on film (for a director other than himself). The plot gives us Holly Martins, a novelist who writes Westerns, on a visit to Vienna at the behest of his old college chum Harry Lime, who has offered him work. When Martins arrives, he learns that Lime has apparently died in a traffic accident …but the writer is not convinced. Something is amiss. He investigates the circumstances surrounding Lime’s demise, navigating the city’s unseemly depths. In the process his innocence is overwhelmed by the paranoia that pervades the Viennese black market as well as the distrust generated by a city that has been carved up by uneasy postwar Allies. The narrative’s climax, set in the sewers, is among the most memorable in film history, while the score, which features the nimble plucking of zither master Anton Karas, is atmospheric to the point of transcendence.

Two more Reed/Greene collaborations are also part of this series. The 1948 gem The Fallen Idol and the 1959 Alec Guinness vehicle Our Man in Havana.

The Fallen Idol is a personal favorite of mine. It is a taut morality play seen through the eyes of a young boy. Philippe, the son of a French diplomat, is neglected by his father; he has bonded with the family’s butler, Baines. The latter is estranged from his wife and Philippe discovers that Baines is having an affair with a pretty French secretary. The butler passes his lover off to Philippe as his relative, and asks the child to keep this knowledge secret. Then Philippe witnesses Baines’ wife falling to her death: Was it murder? Will the boy keep quiet? This film festers with secrets and lies, an example of a territory that was called Greeneland. Ralph Richardson plays Baines; there is a plum role for Jack Hawkins as the detective. Ten-year-old Bobby Henrey is haunting as Philippe; this one of only two feature films this talented boy made.

Richard Attenborough in 1947’s “Brighton Rock.”

Our Man in Havana drips with deliciously sly irony. Blending comedy and drama, the plot revolves around a middle-aged British expatriate named Jim Wormold (Alec Guinness) who is a proprietor of a vacuum cleaner business in pre-Castro Cuba. The British Secret Service enlists him to organize a spy ring, but Wormold is far from competent. He puts together a spy network (made up of names taken from the membership of a country club) and sends back home fibs about successful operations, the most spectacular being a plan for a super weapon, which is a drawing of the internals of a vacuum cleaner. Soon Wormold is on the radar of the Cuban authorities and finds himself trapped in his own web of lies. Innocent bystanders start dropping like flies. An all-star cast includes Burl Ives, Maureen O’Hara, Ralph Richardson, Noël Coward, the incomparable Ernie Kovacs, and a young Rachel Roberts as a prostitute, a year before Saturday Night and Sunday Morning would make her a star.

One of Greene’s lesser cinematic achievements is the 1967 film The Comedians. Clearly meant to be a vehicle to pair (once again) Richard Burton with on-again, off-again wife Elizabeth Taylor, the plot line focuses on Burton’s character, Brown, a cynical owner of a hotel in Haiti who has to make some difficult choices as the country unravels under the murderous dictatorship of Papa Doc Duvalier.

The fifth entry in the MFA’s Greene fest is Brighton Rock, a 1947 film (there was a remake in 2010) that centres on the neurotic Pinky Brown (Richard Attenborough), a smalltime hood whose gang is offering ‘protection’ around the racetrack in Brighton, England. The thugs’ unsavoury doings include a murder that they apparently get away with. The police believe it to be a suicide, but Ada, who was with the victim just before his death, is unconvinced.

What made Greene’s screenplays distinctive? Considered by many critics to be one of the century’s greatest novelists, he was, at least in the early part of his career, fascinated by movies. During the 1930s Greene was a wittily acerbic film critic for The Spectator. It was then that he acknowledged the talent of director Carol Reed. Perhaps he sensed that they shared a similar vision. Looking back now, it is easy to see the pair as wise forerunners of British film noir, though their prescience goes farther than that. They, and in particular Greene, were exploring the idea of the protagonist as anti-hero well before it became a popular trope in the 1950s and ’60s.

Greene converted to Catholicism at the age of 26, and his scripts constantly explore the divide between moral and amoral behavior, often focusing on acts of sin that hint at the existence of grace. He created characters who seemed (and in some instances could be) reprehensible, but somehow their behavior dramatized more than the limits of humanity — there were suggestions of spiritual possibility, intimations of something beyond the prosaic.

Paul Dervis has been teaching drama in Canada at Algonquin College as well as the theatre conservatory Ottawa School of Speech & Drama for the past 15 years. Previously he ran theatre companies in Boston, New York, and Montreal. He has directed over 150 stage productions, receiving two dozen awards for his work. Paul has also directed six films, the most recent being 2011’s The Righteous Tithe.

Tagged: Brighton Rock, Carol Reed, Graham Greene, Museum of Fine Arts, Paul Dervis, screenwriter, The Comedians, The Third Man

Editor’s Note:

Those who want to read more about Graham Greene and his thoughts about the movies, including writing screenplays, should pick up The Graham Greene Reader: Reviews, Essays, Interviews & Film Stories (Applause Books). Edited by David Parkinson, the hefty volume contains the novelist, screenwriter, critic, performer, and adaptor’s reflections on his films as well the terrific movie criticism he wrote for The Spectator.

It turns out that Greene’s favorite of his scripts was for The Fallen Idol because “it is more of a writer’s film than a director’s.” His incisive Spectator reviews (written between 1935 and 1941) make for robustly fun reading. There are plenty of laugh-out-loud lines: “This week we have run the gamut of sex, from the incredible virginities of Girls’ Dormitory by way of Mae West to the leaping stallions of Horotagy. For dignity and decency the horses have it.” The phrase “incredible virginities” suggests the hand of a master.

For Greene, film criticism in the face of determined banality had no choice but to react with satire “…to make a flank attack on the reader, to persuade him to laugh at personalities, stories, ideas, methods, he has previously taken for granted…The cinema needs to be purged with laughter, and the critics, too…. Indeed, I am not sure whether our fellow critics are not more important subjects for our satire than the cinema itself, for they are doing as much as any Korda or Sam Goldwyn to maintain the popular middle-class Book Society status quo.”

Bill. Terrific suggestion. I am more than willing to subject myself to his slings and arrows and a great companion for the series.