Album Review: When Nobody/Everybody is Listening – The Basement Tapes

It may seem a bit like overkill, and in many ways it is, but that all depends on your perspective.

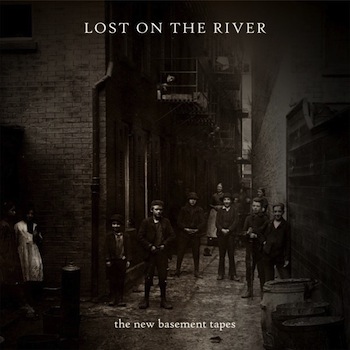

The musicians on the “Lost on the River: The New Basement Tapes.”

By Rob Ribera

We’ve heard a great deal from Bob Dylan these last few weeks. First, the arrival of the long-awaited release of the Complete Basement Tapes, with nearly 150 songs, outtakes, alternate versions, coughs, crack-ups, and miss-cues. It was heaven for those who have been anxious to hear every whisper uttered during the famed sessions. And now, the second half of the nostalgic odyssey steps up to the plate: the release of Lost on the River: The New Basement Tapes and an accompanying documentary, Lost Songs: The Basement Tapes Continued, directed by Sam Jones, which airs on Showtime tonight.

It may seem a bit like overkill, and in many ways it is, but that all depends on your perspective. Dylan has been in the official bootleg business for just about thirty years now, and it is staggering to imagine just how much material is still locked away in the vaults. This release, and the recording of more material that recently resurfaced, gives us our most complete picture yet of one of the most legendary summers in rock and folk history.

“Self-consciousness ends the creative process,” opines T Bone Burnett about half way through Lost Songs. He’s talking to one of the artists he’s gathered together to record newly discovered lyrics that Dylan penned during his legendary summer of 1967. This is Burnett’s attempt to keep things as loose and free as possible, mimicking the famed summer when Dylan and the Band just hung out recording music all day in a Woodstock basement—tunes that nobody was supposed to hear.

That last element has always been one of the more interesting paradoxes about the Basement Tapes. The latter was the eventual title for the recordings, after their first incarnation under the moniker Great White Wonder, rock’s first bootleg. For a group of musicians who didn’t expect their music to be heard, they sure did a lot of recording. Not that I’m complaining. I’m one of those Dylan fans who eagerly awaits each of his Bootleg Series releases, generally griping that they probably could have released even more outtakes and alternate versions.

But I digress. If the legendary recordings done in the basement of Big Pink were all about cutting loose while no one was watching, the New Basement Tapes are the opposite. The dusty couches and dimly lit room have been replaced with the spotless recording studios of the Capital Records building in Los Angeles. Burnett brought together some big names — Jim James, Elvis Costello, Rhiannon Giddens, Marcus Mumford, and Taylor Goldsmith — and tasked them with creating music for the lyrics (somehow forgotten, squirreled away for nearly half a century) that Dylan left behind that year.

This type of thing has happened before. Dylan himself recounts his visit to Woody Guthrie’s home back in the early ’60s in his autobiography, Chronicles. Finding a young Arlo Guthrie at the door, the two went looking around for some of the senior Guthrie’s lost lyrics. They never found them. They finally showed up in the ’90s. Billy Bragg and Wilco took a crack at crafting new songs for them. Jim James joined The New Multitudes only a few years ago to record another group of lost Guthrie lyrics. Dylan himself recorded a new Hank Williams tune in 2011. Each of these collaborations are fascinating efforts at rejuvenation, the past dragged into the present by musicians who want to honor the spirit of the material. Some of these efforts touch on greatness, others wind up being forgettable.

It’s difficult to judge these new songs: many were simply meant to be no more than scraps of sporadic fun, though some amount to more than that. Not all Dylan is gold, but some of these shine. The opening track, “Down on the Bottom,” led by Jim James, is particularly strong, as are the contributions of Marcus Mumford (“Kansas City”) and Rhiannon Gidden (“Spanish Mary”) I hate to say it, but Elvis Costello’s interpretations left me a little cold, though on the deluxe version of the album his take on “Golden Tom-Silver Judas” is quite nice. Taylor Goldsmith, however, who dismisses his own presence in the documentary as the outsider in a group of stars, adds a nimble touch to his contributions, particularly “Florida Key” and “Liberty Street.” These subtle takes reflect the narrative quality you would expect from the front man for Dawes.

Yes, some of these songs were shavings, but they could have been turned into something a little more complete and well rounded than what they end up as. Still, as Jim James asks during the recording process, “What is a song? What is the possibility of a song? A song is limitless.” This is a wonderful notion, and these songs and the film are really about the vagaries of the creative process. Costello holds up a cell phone recording that he did in the confines of an airplane bathroom. Giddens worries that her lack of preparation will affect the quality of her work after learning that some of the other members spent long hours coming up with melodies. Goldsmith, in a room of well-known musicians, dwells on his lesser stature. Mumford reveals that he only writes a song every six months or so unless something really comes together in his head.

This serendipity is part of what made the original Dylan recordings so compelling, and, of course, what makes all sort of bootlegs and unreleased recordings desirable. We want to speculate (deeply) on the whys and the hows, even when the songs are deemed throwaways. And, if only to gratify our curiosity, the new material is worth it. Watching some of folk’s present-day figures grapple with fifty-year-old lyrics is more than just intriguing; in the end, it creates a fertile dialogue with the past — in very much the same way that Dylan and his contemporaries hoped to reach back into music history in the ’60s. At one point, Costello remarks that they already have 23 songs in the can, and they might hit 50. There’s only 20 songs released on the “deluxe” version of Lost on the River: The New Basement Tapes, so we’re left to believe that there’s a lot more music coming. I look forward to hearing it.

Rob Ribera is a filmmaker and music video director in Boston. He is the co-creator of the music website Sleepovershows.com, and is currently working on his Ph.D. in American Studies at Boston University.