Jazz Review: Jimmy Giuffre — Through the Lens of Dave Douglas and Riverside

In moments like these, the band Riverside captures the Jimmy Giuffre ideals of sonority and counterpoint — where even the drums act as another complementary linear voice.

By Jon Garelick

The scope of the composer and reed player Jimmy Giuffre’s music is so broad that you could approach it from just about any angle and no one would be able to tell you that you’re doing it wrong — chamber jazz, free jazz, bebop, big band (he wrote the Woody Herman anthem “Four Brothers”), or a concerto for soloist and strings. They’re all legitimate approaches to the Giuffre way.

I say Giuffre’s “way,” not his compositions, because that’s the approach that’s being taken by the band Riverside, which comprises trumpeter Dave Douglas (who studied with Giuffre for a semester at New England Conservatory), bassist Steve Swallow (who played with Giuffre at two different points of the reedman’s career along with the pianist Paul Bley), and Canadian brothers Chet (reeds) and Jim (drums) Doxos, who never met Giuffre.

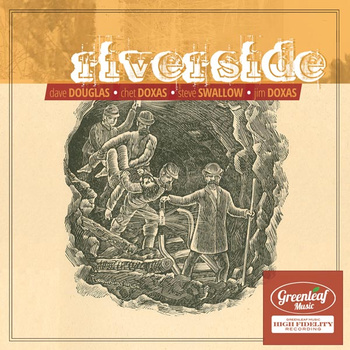

Riverside has a new self-titled album on Douglas’s Greeleaf Music label, on which they play only one piece by Giuffre (“The Train and the River”), and another that he covered (Trummy Young and Johnny Mercer’s “Travelin’ Light”). The other nine tunes on the record are originals by Douglas and Chet Doxas. An album note tells us that it was created in memory of Giuffre and that it draws inspiration from the “many trails” he blazed in “melodic invention, rhythmic subtlety, and true freedom in the practice of improvisation.”

At the Regattabar in Cambridge on Thursday night Riverside showed themselves reflective of the Giuffre way on several fronts. For one, Giuffre’s incorporation of spirituals, blues, folk music, and folk-type tunes into his jazz compositions is of a piece with Douglas’s own recent work, especially his album Be Still (2012), with the singer-songwriter Aoife O’Donovan. At the Regattabar, Riverside played Douglas’s arrangement of the early 18th century composer Isaac Watts’ “Devotion,” taken from a shape note singing book, and Doxas’s equally spiritual “Old Church, New Paint.”

The Giuffre style also manifested itself in the constant counterpoint between Douglas and Doxas either on tenor or clarinet, often with the ever inventive Swallow creating yet a third line. But, though the interplay was often subtle, and the tunes very shapely indeed, this was not the kind of music that Swallow played in his first outing with Giuffre, on acoustic bass, from 1961 to ‘62. Or the music of Giuffre’s late ’50s career, which was often drummerless.

Giuffre (1921-2008) said of that early period of his music that he was trying to create “jazz with a non-pulsating beat.” In a definitive 1997 Mosaic reissue of Giuffre’s mid-late ’50s output, he’s quoted regarding the beat as being “implicit . . . acknowledged but unsounded.” He didn’t want “the insistent pounding of the rhythm section” distracting from the sound of the soloists and the melodic line.

The “acknowledged but unsounded” beat was characteristic of Giuffre’s way, but it wasn’t his only way — and it didn’t mean no drummers. And, implied beat or not, Giuffre swung hard — you can see him “acknowledging” the beat with his unrepressed bobbing up and down through the Jimmy Giuffre Three’s performance of “The Train and the River” in the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival documentary Jazz on a Summer’s Day — Giuffre on tenor with guitarist Jim Hall and Bob Brookmeyer on valve trombone.

Riverside (Dave Douglas, Steve Swallow, Chet Doxas, Jim Doxas) at the Regattabar on April 17. Photo: Sue Yang.

At the Regattabar, Jim Doxas was subtle and creative throughout the night, and his beat was often indirect, but he also acknowledged it, at times heavily. In the Jimmy Giuffre Three’s hands “The Train and the River” swings hard but undulates softly. In Riverside’s version, it blared like an anthem.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it sure is different. There were other felicities in Riverside’s treatment of Giuffre’s music. Giuffre was obsessed with timbre and sonorities, always coming up with inventive combinations, like the reed/guitar/trombone matchup or, in the case of “The Sheepherder,” from 1956, a blend of clarinet, alto clarinet (Buddy Collette) and bass clarinet (Harry Klee). For a time, Giuffre played clarinet exclusively, restricted, he said, by his limited technique to the dark, evocative low, chalumeau register. Here, Doxas excelled, especially in tandem with Douglas on the trumpeter’s minor mode “Front Yard,” over the swish of Jim’s brushes. On the disc version, there’s a wonderful duo passage for clarinet and bass, with just the barest smattering of drums. In moments like these, the band captures the Giuffre ideals of sonority and counterpoint — where even the drums act as another complementary linear voice.

Throughout the night, melody lines passed back and forth, overlapped, fell into unison harmonies, then split apart again. “Backyard” (the companion piece to “Front Yard”), grew free and agitated, then settled into a hard funky beat and went out with the subdued theme and a big chord from Swallow.

There were times, especially in the beginning of the set, where I wished the band showed as much concision as Giuffre and meandered a bit less. But by the end of the night they’d won me over. It was fun to hear Douglas explode over the boppish swing of Doxas’s “Big Shorty” (a tribute to Giuffre’s work with Shorty Rogers) and to hear the hooky riffs of Douglas’s “Handwritten” (also from Riverside). Since the show, it’s been pleasure to return to the Riverside album and to savor anew their poised take on “Travelin’ Light” — based, as Douglas said in concert, on Giuffre’s arrangement, but “we’ve made our own thing out of it.” That’s the Giuffre way, too.

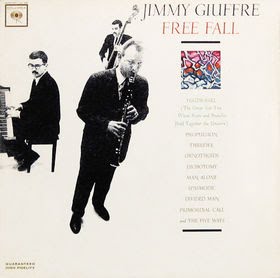

Inevitably, the Riverside show led me back to other Giuffre recordings — the Mosaic set (which you can now find most of on the new budget UK series, Real Gone Jazz, as the 3-CD Jimmy Giuffre: Seven Classic Albums), or the 1992 ECM reissue, Jimmy Giuffre 3, 1961, which includes Fusion and Thesis, the two albums that Giuffre recorded with Bley and Swallow (on acoustic bass, before his permanent switch to electric bass guitar) for Verve. Then came the freely improvised Free Fall with Bley and Swallow on Columbia — produced by Teo Macero, and so free that the label immediately dropped him.

Although he continued to perform, Giuffre didn’t release an album for another 10 years after Free Fall. But in June, Elemental Music will release the two-disc Jimmy Giuffre 3&4: New York Concerts, with two performances from 1965 (it’s now available as a pre-order on Amazon). Here is Giuffre in a trio with bassist Richard Davis and drummer Joe Chambers and a quartet with Chambers, pianist Don Friedman, and bassist Barre Phillips. It’s an important addition to the Giuffre story. Playing tenor sax once again, he’s a bit more aggressive with his tone, but melody line and group counterpoint are as crucial as ever. There are tunes, but also a lot of free improvisation. And when he exchanges phrases with Friedman’s Cecil Taylor-like rumblings, you can read him as an equal partner in the creation of the ’60s avant-garde. So it’s easy to agree with Paul Bley’s assessment in the liner notes: “The two most important figures in the early days of the avant-garde were both composers and reed players: Ornette Coleman and Jimmy Giuffre.” In fact, with the trio on the New York album, Giuffre plays Coleman’s “Crossroads” (also known as “The Circle with the Hole in the Middle”).

In later years, Giuffre would reunite with Bley and Swallow (on electric bass this time), and play and record with students and colleagues at New England Conservatory. His is a long story, and it isn’t over yet.

Jon Garelick is a freelance writer who lives in Somerville, MA. He blogs at jongarelick.com and can be reached at jon.garelick4@gmail.com and followed on Twitter at @jgarelick. He is former arts editor of the Boston Phoenix.

Tagged: Chet Doxas, Dave Douglas, Jim Doxas, Jimmy Giuffre, Riverside