Opera Album Review: Muslims vs. Christians in 10th-Century Spain, Portrayed in an 1881 Gounod Opera (World-Premiere Recording)

By Ralph P. Locke

Gounod was no mere purveyor of gentle sentiments. This 1881 opera, superbly performed, shows plenty of drama and grit.

GOUNOD: Le tribut de Zamora

Judith van Wanroij (Xaïma), Jennifer Holloway (Hermosa), Juliette Mars (Iglésia, a young female slave), Edgaras Montvidas (Manoël), Tassis Christoyannis (Ben-Saïd), Boris Pinkhasovich (Hadjar), Artavazd Sargsyan (the Alcade, the Cadi), Jérôme Boutillier (king, Arab soldier). Munich Radio Orchestra, Bavarian Radio Chorus, conducted by Hervé Niquet. Bru Zane BZ1033 [2 CDs] 141 minutes

I didn’t know what to expect when I received this world-premiere recording of Gounod’s last opera. Le tribut de Zamora was first seen at the Paris Opéra in 1881 and received productions in many theaters (including Vienna, Prague, Turin, and even New Orleans and the Algerian city of Constantine), but it eventually disappeared from the boards. Gounod is known to be a supremely lyrical, somewhat even-tempered composer. Two of his works are regularly seen on the opera stage and encountered in fine recordings: Faust and Roméo et Juliette. But he composed 11 others. Some of these are very lighthearted, such as Le médecin malgré lui, which was much appreciated when revived in 2018 by Boston’s Opera Odyssey under Gil Rose.

Gounod, I feared, was simply the wrong composer for a broad-scaled four-act grand opera dealing with tensions between politically dominant Arabs (“Saracens” or “pagans”) and subjugated Christian townspeople in 10th-century Spain.

I needn’t have worried. Le tribut de Zamora is sonorous, tuneful, effectively written for the voices, and (as Saint-Saëns noted in an enthusiastic review) beautifully scored. The nasty Arab leader Ben-Saïd is brilliantly limned, as are the innocent Spanish-Christian couple, Xaïma and Manoël, who stand up to him. The chorus of Spanish Christians has similarly powerful music when it protests the cruelty of the ruling Muslim authorities and when it recalls the heroism of the Christians at the battle in and around the town of Zamora some years earlier.

I have just summarized the characterizations as seen in the libretto. The historical evidence behind many events in the work is questionable, as the accompanying small book all too briefly hints (p. 57). There was indeed a famous battle (the Battle of Alhandic) in 939 AD, which ended with the troops of Abd-ar-Rahman III breaching the walls of the fortified town of Zamora. The libretto claims—I do not know on what evidence—that the Arab rulers then demanded a horrifying “tribute”: namely, that each of several cities across Spain hand over 100 young women to be auctioned as slaves. Thus the opera’s title is a kind of cultural accusation: meaning, more or less, “The Shameful Demand that the Arab Leaders Made after Their Victory over Christian Forces at Zamora.”

The opera takes place in the city of Oviedo (in northwest Spain, on the coast of the Bay of Biscay). One of the first of the town’s victims, chosen by lot, is the opera’s heroine Xaïma. Operagoers must have been expected to empathize with the Christians against the portrayed-as-despicable Muslims. Indeed, at one point the tenor-hero Manoël and the baritone-baddy Ben-Saïd (who is the ambassador of the Caliph of Cordoba, and who has locked Xaïma up in his harem) get into a fight. Manoël is promptly disarmed by Ben-Saïd’s soldiers, and Ben-Saïd ends up knocking Manoël down, pressing a knee into his chest, and holding a yataghan (curved short saber) to his throat. This culminating tableau was ripe for being copied in the illustrated press of the day, as can be seen on p. 76 of the hardcover book that accompanies the two CDs.

This scene’s portrayal of Arab Muslims as rapacious and cruel probably reflects events and attitudes of the 19th century more than those of the 10th century. Beginning in 1830, France had gradually conquered Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco, and this sometimes involved putting down rebellions (e.g., in Algerian Kabylia, in 1871-72). The opera’s portrayal of the Arabs is, in essence, defamatory. Arabs ruled Spain for centuries in a manner that, in many ways, was more enlightened and tolerant than was Christian rule over the rest of Europe at the time, never mind what the reimposition of Christian rule over the Iberian peninsula (completed in 1492) would involve: namely the expulsion, forced conversion, or outright murder of all Muslims and Jews.

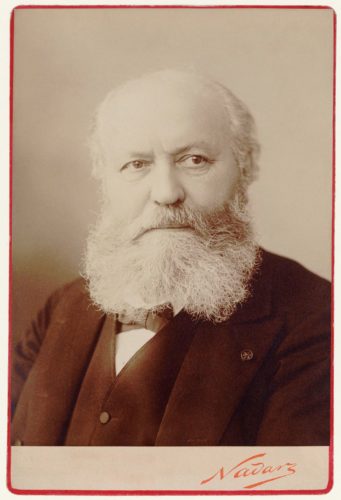

Composer Charles Gounod in 1890.

Operagoers today are accustomed to setting aside the prejudicial ethnic portrayals in many operas. For example, few of us share the revulsion toward the Gypsy woman Azucena that is expressed by Ferrando and Count di Luna in Il trovatore. It is thus at least possible that Le tribut de Zamora could be successfully staged and appreciated for its many strengths. Still, an opera company would be well advised to contextualize the work in carefully researched program notes and pre-performance talks.

I said that the music is beautifully crafted. There are, for example, brief but delightful act-preludes and marches. The deliciously exotic-sounding “March of the Captive Women,” I suspect, may have influenced the Arab Dance in Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker. Other moments of overt exoticism include some swirling modal phrases (in the oboe or other winds) that are clearly meant to sound—depending on the context—Spanish or Middle Eastern, plus (in Act 3) a spirited Spanish Dance inspired by the entr’acte to Act 4 in Carmen, and a particularly intoxicating Greek Dance. (A string of short excerpts from the recorded performance can be heard and viewed on You Tube.

Enormously involving is the music for the crucial slave auction that ends Act 2. It begins with a motoric figure that seems modeled on the gambling scene in La traviata, but it then sequences upward (at minute 2:00 in the link just given) with a dramatic intent specific to the bidding war between the tenor and baritone over the soprano, Xaïma. The passage then builds to a big ensemble on a broad tune—as in an Italianate largo concertato—to which each character’s words lend a specific coloration. As so often in operatic ensembles, one must read the libretto to “hear” what each character is thinking.

I admit that some moments are fresher and more effective than others. The patriotic hymn to the courageous Spanish soldiers of the Battle of Zamora (which ends the Act 1 Finale) is uncomfortably similar to the music of the final trio in Faust. The parallel seems even clearer when a solo voice—Hermosa—reprises the passage in its entirety in Act 3 (at minute 3’55” in this track). Also, the big, attractive tune sung by Hermosa, then Xaïma, and finally the two of them together (in the same duet: at minute 2’ 55” in this track) reminded me of “Amami, Alfredo,” from La traviata. But just when things are sounding a bit warmed over, Gounod can introduce a cherishable surprise, such as a passage for Hermosa (just before that big tune: minute 2’ 10” in that same track) with elegantly flexible phrase structure. What I earlier called the “broad tune” in the Act 2 finale (soon after the beginning of this track) demonstrates an admirable, almost Berliozian control of melodic structure.

The work can be faulted (as it was at the time) for having a stop-start quality across an act. But that is true of many works in the French genre of grand opéra by Meyerbeer, Halévy, Berlioz, Verdi, and others. By the 1880s, the French musical world was obsessed with trying to keep up with the Germans, which, in the operatic realm, meant Wagner. But surely we do not need to fight those battles today and can instead appreciate a work for what it is, rather than what it isn’t.

Besides, it seems odd to me for historians and critics to grumble when a late-19th-century opera has clear, functional divisions between recitative-like sections and the vocal numbers proper (and between the several movements or sections within each of those vocal numbers). Nobody, after all, objects to the stopping and starting in contemporaneous operettas by Offenbach or Johann Strauss, Jr.—or in even the strongest Broadway musicals!

For the most part, the performances here are vivid and persuasive, making a strong case for the work. The four main singers (Judith van Wanrooij as Xaïma, Jennifer Holloway as Xaïma’s long-lost mother Hermosa, Edgaras Montvidas as Manoël, and Tassis Christoyannis as Ben-Saïd) incarnate their roles effectively, singing with great beauty and, at the same time, acting through the voice. Van Wanrooij gets to sing the one passage that is somewhat well known today, “Ce Sarrasin disait” (part of the lovers’ Act 1 duet). Joan Sutherland has recorded it with glorious vocal aplomb, but van Wanrooij makes it her own, conveying the affectionate words in a touching, seemingly spontaneous manner. I have returned to this one track several times, enjoying van Wanrooij’s marvelous combination of vocal control and dramatic appositeness.

At times, van Wanrooij’s and Holloway’s voices are hard to tell apart, especially when Hermosa (the lower of the two roles) is singing in her high register, as in the extended scene of the women’s first meeting, in Act 2. (Or, rather, they think it’s their first meeting. Hermosa, currently in a state of madness, will turn out to be Xaïma’s long-lost mother and, recognizing this, will regain her sanity.) Some future performance of the work might profitably cast a mezzo with a deeper voice in the role, as is normally done with Verdi’s aforementioned Azucena (another woman who is both mad and a character’s unrecognized mother). But I hope that this will not come at the expense of the clarity and precision with which Holloway here attacks the role’s many high notes (and several startling passages of coloratura). Perhaps the role is nearly impossible to embrace in all its respects, but that is not unusual in the world of opera. (Notable instances are the wide-ranged soprano role of Abigaille in Verdi’s Nabucco and the title role—for heroic tenor—in Verdi’s Otello.)

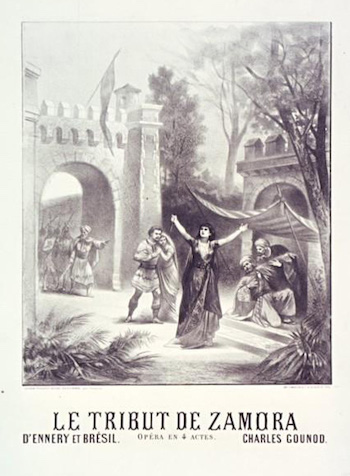

A poster for the premiere production of “Le tribut de Zamora.”

Montvidas is as continuously passionate and convincing as he was in Félicien David’s Herculanum and Benjamin Godard’s Dante. Christoyannis (whom I have previously admired in recordings of songs by Félicien David, Lalo, and Saint-Saëns) excels in the frequent moments of sarcasm and disdain, impressively histrionic at times, but never quite forcing his voice into a pitchless shout. He is even better when he gets to sing sweetly, as in his manipulative Act 3 plea: “O Xaïma, daigne m’entendre” (Oh, Xaïma, please listen to me!).

Boris Pinkhasovich, in the important secondary role of the Arab soldier Hadjar, is communicative, but his voice is somewhat unsteady and lacks fullness in the role’s lowest notes. He does better when interacting with other characters than in his Act 2 solo in praise of war and love. Juliette Mars is wonderful as Iglésia but shows an aged-sounding wobble in a barcarolle (as “a young slave woman”). Artavazd Sargsyan, a marvelous light tenor, sings his two shortish but crucial roles (e.g., the auctioneer of the female slaves) with the total smoothness and clarity that I have admired in several other recordings (e.g., in two Gounod sacred works).

Conductor Hervé Niquet, best known as a Baroque-era specialist, keeps up the pace nicely and varies it as needed. This is some of the best conducting I’ve heard from Niquet in 19th-century repertory. The Munich Radio Orchestra sounds full and clear. The acoustics of the smallish Prinzregenten Theater surely help produce such a fine-sounding result.

In short, this Tribut is another triumph for the “French Opera” series of “CDs+book” made possible by the scholars of the Center for French Romantic Music, which is located in the Palazzetto Bru Zane (in Venice). The essays in the smallish hardcover book that comes with the CDs are as interesting and well informed as we have come to expect from the Center. They are printed in French and in mostly good English, as is the libretto. One gripe: the essay on the image of Spain in French visual art is written in a pretentious style that is sometimes hard to follow in either language.

The illustrations throughout the book are marvelous; some are very detailed and worth looking at with a magnifying glass.

Collectors should note that recordings from the Center, though once widely—if inaccurately—listed as being available from Ediciones Singulares, are now plainly labeled with the words Bru Zane, to indicate that they are produced and distributed by the Center. (Ediciones Singulares was simply the Spanish publishing house that used to manufacture the hardcover book that comes with each CD set.) It is fitting that such a marvelous series is now more clearly associated with the Center (at the Palazzetto Bru Zane)—an admirable organization, at once scholarly and practical-minded, that maintains almost unprecedentedly high standards for new recordings of first-rate yet forgotten operas.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Tagged: Bavarian Radio Chorus, Bru Zane, Hervé Niquet, Le tribut de Zamora, Munich Radio Orchestra, Palazetto Bru Zane