Jazz Album Reviews: The Music of Lerner and Loewe — Back in the Jazz Limelight?

By Michael Ullman

The two new Arbors discs are intended to bring Lerner and Loewe back into the jazz mainstream. We will see what happens. But what wonderful music these two groups have produced!

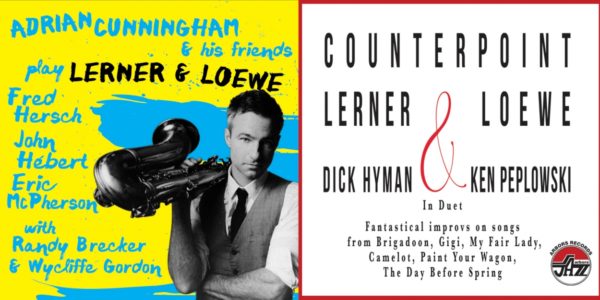

Adrian Cunningham and His Friends Play Lerner and Loewe (Arbors)

Dick Hyman and Ken Peplowski: Counterpoint: Lerner/Loewe (Arbors)

In the 1950s, everyone knew Lerner and Loewe’s music: songs such as “On the Street Where You Live,” “Gigi,” “The Rain in Spain,” and “They Call the Wind Maria.” The tunes were instantly memorable, and they seemed to be everywhere, on the screen as well as on original cast LPs, reaching homes where little other music penetrated. Many of us will remember the film Gigi, where Maurice Chevalier — via his regionally indistinct French accent and with a twinkle in his eye — sang “Thank Heaven for Little Girls.” (The girl in this case was the beautiful French actress Leslie Caron, who didn’t look little to my preteen eyes.) And some will remember the shock when Julie Andrews was not chosen for the movie version of the part she made famous onstage in My Fair Lady.

Several of Lerner and Loewe’s musicals, Gigi as well as My Fair Lady, have an international flavor. No wonder. Frederick Loewe was born in Austria in 1901: his father was a renowned tenor, who originated the role of Count Danilo in The Merry Widow. Viennese operetta had a considerable effect on American musical theater. As a counterweight to Loewe’s cosmopolitanism, Alan Jay Lerner was born in New York City 17 years later. Together, of course, they famously wrote Brigadoon, Paint Your Wagon, Gigi, and My Fair Lady. Their partnership foundered in the ’60s while they were writing Camelot, yet that hit show gave the name to the age: John F. Kennedy’s brief period as our president.

My Fair Lady became an unlikely jazz vehicle thanks to West Coast drummer Shelley Manne who, with Andre Previn at the piano, featured its score on an August 1956 album. They did so fast on the heels of the show’s opening. It was a remarkable stunt, one is tempted to say, but also remarkable musically. It was also a surprising commercial hit that spawned a series of such jazz recordings. In January and February of 1957, pianist Billy Taylor teamed up with arranger Quincy Jones to create a subdued, cool jazz version of the musical which they called My Fair Lady Loves Jazz. In March of that year it was the hard bop drummer Art Blakey’s turn: with Bill Hardman on trumpet and Johnny Griffin on tenor, Blakey played the Loewe melodies, but quickly forgot them, turning the music into unlikely hard bop romps. Blakey’s recording was as rough around the edges as Quincy Jones’s was smooth: pianist Sam Dockery seems to lose himself temporarily on On the Street Where You Live and one or two of the endings are haphazard. In January 1958, trumpeter Shorty Rogers made his record, Gigi in Jazz, four months before Andre Previn recorded Gigi. Oscar Peterson’s My Fair Lady came in 1958, followed by Chet Baker Plays the Best of Lerner and Loewe, a delightfully sensitive and lyrical take on various Loewe compositions.

Perhaps most of these musicians were chasing after the success of Manne’s My Fair Lady, but taken together they form a neat little corpus of jazz recordings. The trouble was, according to Emily Altman, president of the Frederick Loewe Foundation, which sponsored the two new Arbors discs featuring Loewe songs, the buck stopped there, in the late ’50s. (OK — Nat King Cole sang My Fair Lady in 1963.) Several of the team’s songs have since become jazz standards: I have around 30 versions of “Almost Like Being in Love” in my collection, including recordings by Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Sonny Rollins, Nancy Wilson, and much more recently, Brad Mehldau. Rollins, Stan Getz, Bobby Hutcherson and many others have recorded the team’s other standard, “If Ever I Would Leave You.” Much of the rest of Lerner and Loewe has been neglected by jazz players. One is infinitely more likely to hear a Gershwin or Arlen tune in a local club than anything by the creators of My Fair Lady. Perhaps the problem was that the songs were so finely tuned to the dramatic situation of the plots. Perhaps it’s also the lingering sentimentality in scores like Brigadoon, in which a guy falls in love with a girl and a town that only appears every hundred years or so. Yet somehow the lovers get together in a sublime example of long-distance dating.

The new Arbors discs are intended to bring Lerner and Loewe back into the jazz mainstream. We will see what happens. But what wonderful music these two groups have produced! Adrian Cunningham is a saxophonist and clarinetist who spent months studying the Lerner and Loewe corpus before deciding on his sequence of tunes. He is accompanied by one of the most celebrated groups in contemporary jazz: the Fred Hersch trio with John Hébert and Eric McPherson. On two numbers, Cunningham and trio are joined by trombonist Wycliffe Gordon, with Randy Brecker contributing to a couple of tracks as well. (Maybe Cunningham is a revivalist at heart: his earlier record, also with Wycliffe Gordon, was Ain’t That Right: The Music of Neal Hefti for Arbors.)

Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe. Photo: Yousuf Karsh.

Cunningham’s opening number on his Lerner and Loewe project is a hushed, intimate version of “Say a Prayer for Me,” from Gigi, which he plays with sweet expressiveness, accented by the occasional leaping flurry of notes, on clarinet. (The original lyrics are partially humorous: the suppliant sings, “On to your Waterloo, whispers my heart./ Pray I’ll be Wellington, not Bonaparte.”) The delights of the Cunningham rendition, indeed of the whole recording, include the solos — and even the beautifully nuanced introductions — by Fred Hersch. Cunningham begins a bouncy “I Could Have Danced All Night” by himself over drummer McPherson. Then Gordon plays the second A section on trombone, with a bit of a flourish. They go on together, with Cunningham yipping in a momentary stop time, and then playing fluently, and Gordon growling and muttering humorously in the background. Hersch’s ensuing solo is a lyrical marvel.

Cunningham is equally accomplished on tenor, clarinet, and flute, and he changes the sound of each instrument to fit his ideas about the songs. One of Julie Andrew’s celebrated numbers, “Just You Wait,” is played on flute. At first a little threatening, the song begins with a stop-and-go rhythmic pattern by bass and brushes, with Hersch eventually entering stealthily behind them, like a sly cat. It’s an appealing arrangement. Randy Brecker joins the band on a delightful “Thank Heaven for Little Girls”: he takes the first solo in a swinging 4/4. Brecker is also on “They Call the Wind Maria,” which they play swiftly, as if to forestall the sentimentality with which this song is usually performed. Somehow, with Wycliffe Gordon aboard, they transform “I Was Born Under a Wandering Star” into a funk number. It’s one of many small surprises on a beautifully accomplished album.

The duet album, Counterpoint: Lerner/Loewe, by veteran pianist Dick Hyman and clarinetist Ken Peplowski, is altogether a wilder affair. To some extent, it was planned by Hyman, who said, “I prepared our project by arranging chorus-or-so versions of the Loewe melodies, which we could use as basic concepts to launching our improvs.” Those improvs are remarkable. The two play, for instance, a jaunty first chorus of “I Could Have Danced All Night,” followed by a chorus or so of Peplowski’s clarinet, followed by the two engaging in a variety of accompanying techniques, including a walking bass.

That’s just the beginning. Soon—and this happens repeatedly on this disc—they are engaged in a bout of exquisitely nuanced parallel play, both improvising in joyous sympathy with each other’s lines. At one point, Peplowski stops, to take a breath perhaps, and Hyman plays a little figure that the clarinetist immediately imitates. It’s like someone suggested a new subject for a conversation. Peplowski states the melody of “Show Me” soberly, although he interjects a few bird-like high notes where we wouldn’t expect them. “Follow Me” is another remarkable duo improvisation: midway through, the performance almost stops on its previously gay path, and suddenly seems to wander quietly. These two practiced musicians are inventing bravely throughout, while reintroducing us to lesser known songs such as “I Talk to the Trees” and “A Jug of Wine.”

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.