Fuse Theater Review: Liars & Believers’ “Interference” is “Guernica” for Hipsters

The $64,000 question is, if the artists’ concerns gravitated to the Marathon Bombings, why did “Interference”‘s press releases and the program cite Picasso’s “Guernica”?

Interference, directed by Steven Bogart. Presented by Liars & Believers at Club Oberon, Cambridge, MA, February 12.

By Ian Thal

Interference, Liars & Believers’ one-night only “theatrical event,” purports to be “a performance about courage in the face of terror inspired by Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica.” The painting itself had been inspired by a 1937 atrocity committed by German and Italian forces during the Spanish Civil War, and has since become one of the most famed responses to war in the history of modern art, if not the most iconic painting of the 20th century.

Director Steven Bogart and his collaborators put themselves in a challenging position: having to measure up to the standard set by the classic work of art to which they are paying homage. This is not unfair, because homages are always judged in the context of their inspiration: the new work develops a life of its own when it sufficiently reimagines, deconstructs, comments on, and (perhaps) improves the source material.

The relationship of the script with the interpretive and/or improvisational work of the actors and the production crew is no doubt familiar to theatergoers, but Interference has its own particular form, and to understand this form, one may have to consider a social history of the arts in Boston.

Boston’s underground and alternative arts scene has historically resided in unconventional venues, often in industrial buildings left vacant as the New England economy vacillated between boom and bust. Such spaces included Bad Girrrls Studios and 9 Yards Studios in Jamaica Plain, the Berwick Research Institute in Roxbury, Gallery INSEKT and Oni Gallery in Chinatown, and Pan 9 in Allston. Most of these spaces operated under the radar, advertising their programming by word of mouth and via e-mail lists. The programming was often quite eclectic: a given evening could include anything from performance art to improvised music, short films, poetry, stand-up comedy, and performances from some of the less conventional rock bands on the Boston scene. The aesthetic ranged from carefully curated events to variety show /cabaret formats and ’60s-style happenings. Some of these artists would also perform at more above-the-radar venues, such as Mobius, The Zeitgeist Gallery, or The Lily Pad – sometimes in similarly formatted shows.

As developers began to take over the spaces that had long served as artist habitats, most of these venues disappeared, taken over by more lucrative tenants, or. in some cases replaced by fancier buildings. In the ongoing conflict between artists and developers, the former have been losing out fairly consistently for the past two decades or more.

When American Repertory Theater first opened Zero Arrow Street it was with the intent of having a third performance space that would host less conventional fare than the much larger Loeb Drama Center could accommodate. However, when Diane Paulus became the A.R.T.’s artistic director, it was remodeled into Club Oberon, a night club that serves as a home for The Donkey Show, which she and her husband, Randy Weiner, created in New York. According to Geoff Edgers’ 2010 profile of Weiner in the Boston Globe, Weiner owns the trademark to the name “Club Oberon” and receives a monthly royalty for use of the name and theatrical nightclub concept.

This valuable property in Cambridge quickly became one of the few places to host the sort of risky shows that once defined Boston’s underground arts scene. Ironically, with the well-stocked bar and the tiered seating for early arrivals, there’s also the matter of Club Oberon’s poor lines-of-sight: standing at my full height of 5’6” I could only see many of the acts because of my talent for weaving and darting through crowds — shorter, less mobile attendees are often out of luck, as in the case of an acquaintance of mine who left in frustration during intermission at Interference.

For those who were able to push themselves to the front, the most powerful performances of the evening were by the dancer and performance artist Jennifer Hicks. Over a couple of decades, Hicks, a major exponent of Butoh and Butoh-influenced dance in Boston, has established herself as one of the treasures of Boston’s avant-garde. Novelist, poet, and classicist Robert Graves asserted that myth is narrative shorthand for public ritual recorded in art (and, conversely, that the content of ritual is myth). In this sense, Hicks is a mythic performer. Her musculature and movements evoked the political power of Picasso’s painting without rote mimicry of his forms. Boston’s theater scene is diminished by its inability to find ways to utilize a performer of Hicks’ gravitas more often.

Many of the musical interludes and accompaniments were provided by vocalist and keyboardist Singer Mali (who has previously recorded as Mali Sastri) and her long-time collaborator, bassist Anthony Leva. Working with her band Jaggery, Mali has proven to be to be one of the more interesting composers on Boston’s rock scene. Leva uses the full timbral range of his instrument, incorporating not just conventional plucking and bowing techniques, but an asortment of unorthodox percussive attacks. Mali and Leva provided some refreshing consistency in an otherwise irritatingly inconsistent evening, often anchoring the weaker performances. Other musical contributions were also strong – in particular the vocals of Rebecca Kopycinski (who augments her performances with audio loops under the moniker Nuda Veritas) and Liz Adams.

Over the course of the evening, John J. King played Futile the Clown, an aspiring matador who loses his arm during the bombing of Guernica (perhaps referencing the bull and the severed limb in the painting). Unfortunately, King never figures out how to mine the figure of a one-armed matador for its full tragic-comic potential – it is only in the third act that the story became theatrically compelling when Veronica Baron, playing a polymorphously perverse bull, joins King in the ring to the accompaniment of Leva’s virtuoso bass playing which adds a whimsy that recalls composer Carl Stalling’s Looney Tunes scores.

Ruth Lingford’s black and white animations was the only aspect of Interference that explicitly referenced the painting, incorporating a few of Picasso’s figures. Aside from from these images, the montage would inexplicably lurch into sequences of lovemaking and scans from apocalyptic Christian tracts. Thus there is little evidence that Interference took more than superficial inspiration from Guernica – either the painting or the April 26, 1937 bombing.

Some historical background: It was a Monday afternoon that, at the behest of General Francisco Franco, leader of the far-right Nationalist/Falangist junta, planes from the German Luftwaffe and Italian Aviazione Legionaria attacked Guernica, a town of 7000, known to its Basque residents as Gernika. The Basque, also known as Euskaldunak, are an ethnic and linguistic minority indigenous to the region straddling northern Spain and southwestern France. Though the Nazi and Fascist-backed Nationalists often framed the war as one between traditional Catholicism versus godless communism, and though the Republican cause had support from a number of communist, socialist, and anarchist factions, many Basque who threw their lot in with the Republican cause were religiously conservative Catholics who saw democracy as the best instrument for their national aspirations.

The number of casualties has long been a matter of dispute, with the Basque government at the time reporting 1,654 dead and 889 wounded, while some pro-Falangist sources reported such preposterously low casualty figures as 12. Contemporary historians generally estimate the death toll to have been around 300.The bombing broke the morale of the Basque forces, and led to their military surrender to Italian forces supporting Franco, two years before the Nationalists’ 1939 victory. Franco would rule Spain until his death in 1974.

The attack is considered to be one of the earliest examples of a deliberate aerial bombing of a civilian population, and served as a rehearsal for the German practice of “terror-bombing” of civilian populations during WWII. The latter practice contributed to swift Nazi victories in Poland and the Netherlands. By contrast, the British RAF and USAAF only began to reevaluate their moral reluctance to strike city centers in 1942.

Picasso’s painting, created soon after the bombing, was exhibited at the July 1937 Paris International Exposition in support of the Spanish Republican cause eventually finding a temporary home in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Over the decades, the painting became a potent anti-war symbol. Only in 1981, years after both Picasso and Franco were both dead, and Republican government was restored, was “Guernica” exhibited in Spain.

A reproduction of the painting, in the form of a tapestry, was exhibited at the entrance to the United Nations Security Council chambers from 1985 to 2009. During February 15, 2003 press conferences by Secretary of State Colin Powell and UN Ambassador John Negroponte the tapestry was covered by a blue curtain. Legend has it that it was covered up at the request of the Bush administration because it was advocating for war in Iraq. Others say that it was at the request of television news crews covering the event, who complained that it was a difficult backdrop, especially since the horse’s ass appeared right above the head of the speakers.

Like the TV news crews, Interference had little interest in the painting, even though it was the alleged inspiration for the production. When not clowning with King, Baron performed two spoken word pieces: one was a charming (albeit off-topic) second-person narrative about gift-giving, the other was a rambling meditation that somehow led from the suggestion that municipal trash collection was terribly bourgeois to the epiphany that it’s not wrong for us to distinguish between good things and bad things. Can’t we all agree that the use of child soldiers by warring factions in Sudan, Uganda, and Zimbabwe is to be condemned? The monologue was delivered with all the sincerity of someone who has only recently come to doubt the oft-repeated mantra of conflict resolution professionals that “an enemy is one whose story we’ve not yet heard.” Sometimes, the enemy is someone who would rather kill you than tell you his or her story.

This is about as deep as Interference gets. Keep in mind that Liars & Believers are “resident artists” at the A.R.T.

At some point after the intermission, it became clear that inspiration for Interference is not “Guernica,” but the April 15, 2013 Boston Marathon Bombings, and a muddled realization that terrorism is not just something that happens in the Middle East (by comparison, during the Second Intifada, Israeli civilians experienced a bombing of similar scale every few weeks), or lower Manhattan (I write these words in my apartment, a mere ten-minute walk both from where the accused perpetrators, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev lived.)

The parallels between the two bombings are extremely weak. Franco and his German and Italian allies were not only motivated by a fascist ideology, but also by strategic considerations: a desire to quash Basque national aspirations and destroy any vestige of democracy in Spain. The ideology of the Tsarnaevs, by contrast, was one of Islamic Jihadism – an ideology, that over the dozen years or so since the destruction of the Twin Towers, many Americans, whether they are on the political left or the political right, have made little effort to understand. The Tsarnaevs had no strategic goal: their only intent was to turn a high profile civic event into a spectacle of carnage. It is as if, by some sort of bizarre metaphorical displacement, they were striking a blow both against a perceived U.S. war on Islam and Russia’s suppression of Chechnyan national aspirations. The bombers of Guernica had airplanes and armies; the Tsarnaevs had improvised explosive devices and consumer electronics.

On April 15, I was still serving as community editor of The Jewish Advocate. Having interviewed both counter-terrorism experts and survivors of terrorist attacks, I was somewhat prepared for the news feed images of blood splattered on the Boylston Street sidewalks and of the wounded, their limbs having been instantly severed by the blast, being carried to triage. Yet, when I checked social media to see if my friends were safe, I angered many of them by responding to the mantra of “I hope everyone is alright” with an account with what I already knew about the carnage. Quite simply, many of my peers (including some of those at Oberon on February 12) had no conception of the sort of mind that could plan such an attack nor the sort of carnage such an attack causes.

This had not been my first brush with terrorism since moving to the Boston area. On December 30, 1994, John Salvi, a Catholic anti-abortion gunman, entered and opened fire on the staff of two Planned Parenthood clinics in Brookline, killing two and wounding five. One clinic was not only a short walk from where I lived at the time, but it was where, just days earlier, I had picked up my then-lover’s birth control pills. If this sort of attack is not called “terrorism,” it is because the perpetrator’s anti-abortion beliefs reflect the deep-seated position of one of the two major political parties in the United States.

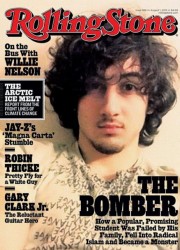

When Bogart’s collaborators did choose to directly address the Boston Marathon Bombings, as with Sophia Cacciola and Michael J. Epstein’s short film about a serial killer known as “The Sexy Strangler,” the result has been superficial. “The Sexy Strangler” would be very much at home on a humor website or as part of a cabaret night. Its only serious point of reference with the bombings is as another example of the “killer as a pop-culture icon” meme, as in the case of the infamously glamorous Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Rolling Stone cover. Never mind that the Tsarnaev brothers probably weren’t looking to become pop-culture icons, and neither Generalismo Franco nor Generalleutnant Hugo Sperrle were looking to be on the cover of Rolling Stone.

Despite a handful of excellent performances, the evening as a whole was confused. Bogart was billed as the director, but he provided very little sensible direction in a heavily padded and conceptually confused two-and-a-half-hour show. A performer in day-glow exercise gear running in place several times over the course of the evening was one of the lone attempts to provide transitions. Generally, a chaotic ensemble of performers milled through the audience wearing surgical masks and forehead lamps. Perhaps there was too little rehearsal time for any director, no matter how talented, to generate a cohesive show out of such diverse elements, but the truth is that most of the contributing artists ignored the themes of the painting and its historical context. If ever a show needed a dramaturg to keep the director and collaborators on point, this was it.

The $64,000 question is, if the artists’ concerns gravitated to the Marathon Bombings, why did the show’s press releases and the program cite “Guernica”? Are Boston’s bohemians so uncomfortable with openly expressing solidarity with their own city that they have to filter them through a pretend show about the Spanish Civil War? Some attendees will surely argue that the show was meant to be “thought-provoking” — but how many will be able to articulate what they were supposed to think?

Ian Thal is a performer and theatre educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere, and on occasion served on productions as a puppetry choreographer or dramaturg. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and is currently working on his second full length play; his first, though as-of-yet unproduced, was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. Formally the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled From The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report

Tagged: American Repertory Theater, Boston Marathon Bombings, Club Oberon, Guernica, Interference, Jennifer Hicks, Liars & Believers, Pablo-Picasso