Opera Album Review: The Love of a Fish-Man for a Terrestrial Woman, French-Baroque Style

By Ralph P. Locke

A masterful composer of French Baroque violin sonatas displays another side of his immense talent in this first-rate new recording of his Scylla et Glaucus.

Jean-Marie Leclair: Scylla et Glaucus

Chiara Kerath (Scylla), Florie Valiquette (Circé), Mathias Vidal (Glaucus), Victor Sicard (chief of the peoples, and other roles).

Il Giardino d’Amore, cond. Stefan Plewniak.

Chateau de Versailles Spectacles 68 [3 CDs] 163 minutes

To purchase, click here.

Jean-Marie Leclair’s Scylla et Glaucus is the fourteenth in a series of French-opera recordings from the record label Chateau de Versailles Spectacles. CdeVS (if I can abbreviate it that way) won an award for “best label” in 2022 at the International Classical Music Awards. I previously praised two other offerings from the same recording firm: Vivaldi’s short opera La Senna festeggiante and the 1761 version of Rameau’s Les Indes galantes.

The new offering is one of CdeVS’s liveliest and most accomplished. It surprised me, because I had only previously encountered Leclair (1697-1764) as a composer of violin sonatas and violin concertos, some of which continue to pop up on concerts (e.g., a sonata, performed by Gil Shaham at the New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall in 2018). Yet here that same composer is with a full-length opera, first performed at the Paris Opéra in 1746, when Rameau — the presiding master of French-Baroque opera and opéra-ballet — was still alive and composing major stage works. To give a fuller historical context, the much younger Gluck was already composing skillful Italian operas in Vienna at this point, including one, Orfeo ed Euridice, that is intensely dramatic in new ways and that he would later expand for performances in Paris. And, a mere six years after this Leclair opera, the philosopher and amateur composer Jean-Jacques Rousseau would offer a short rural-life opera Le Devin du village, a pointedly “naïve” work for which he wrote both the words and the music. Le Devin aimed at blowing away all the traditions of grandeur and sophistication (and praise of aristocratic rulers and evocations of ancient gods and goddesses) that had been central to both French and Italian operatic traditions for many decades. Rousseau’s Devin succeeded, becoming a major point of reference in aesthetic debates at the time and finding its way into music-history textbooks up to our own day.

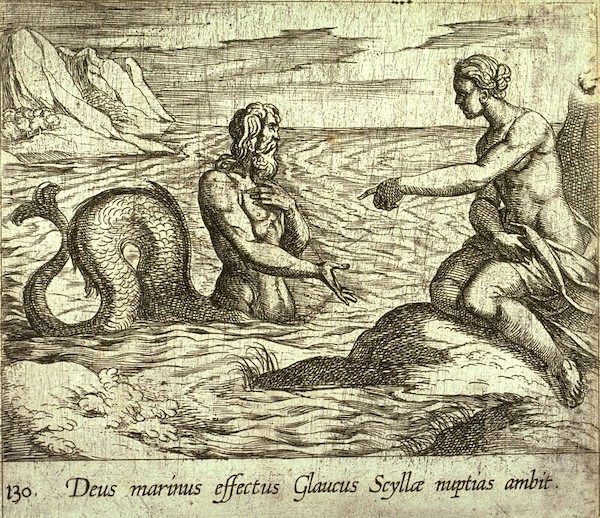

Leclair shows no such revolutionary tendencies. Instead, what we have here is a perfectly realized specimen of the “tragédie lyrique” genre, as created by Lully and enriched by the aforementioned Rameau. The plot involves the unrequited love of Glaucus for the nymph Scylla. Glaucus, according to ancient Greek legend, was once a fisherman but ate a magical herb that gave him a fish’s tail and fins. Later visual artists delighted in showing his massive tail, but some let him have arms with which to yearn visibly for Scylla.

In Leclair’s opera, Glaucus seeks help from the sorceress Circe. (See my recent review of another highly effective Circe opera from the Baroque era, mostly in German, by Reinhard Keiser.) Circe, who has her own emotional needs, falls in love with Glaucus; Scylla goes mad; and Circe turns Scylla into an immense rocky outcropping that will be deadly to sailors. (This is the background to the Greek legend that Scylla was a fearsome monster on one side of a strait and Charybdis was a no less dangerous being on the other side. Hence the expression about the difficulty of charting a safe course between closely spaced dangers: finding oneself “between Scylla and Charybdis.”)

Antonio Tempesta, Deus marinus effectus Glaucus Scyllae nuptias ambit (Scylla and Glaucus), pl.130 from the series Ovid’s Metamorphoses. 17th century.

All this is carried out in music of constant interest and variety, through numerous short arias interspersed with many lovely and energetic dances. The foot-stomping “Dance of the Woodland Creatures” that ends Act 1 could easily become a standard feature on orchestral concerts of Baroque music. (For further information on Leclair’s opera, its plot, its music, and its production history, see Graham Sadler’s detailed entry in OxfordMusicOnline.com and Neal Zaslaw’s 1979 article in Cambridge Opera Journal.)

The singing is marvelous, as one would expect with such names in the cast as sopranos Florie Valiquette and Chiara Skerath and tenor Mathias Vidal, all of whom I have praised here previously. Violinist-conductor Stefan Plewniak leads a continuously engaging performance (with an orchestra of 23 and a chorus of 15). The acoustics are marvelously balanced; presumably it was made in the famous small opera house at the Versailles royal chateau. The hall (constructed in 1763-70) was built entirely of wood — even the pillars — in order, I’ve heard, that music performed there would resonate as marvelously as it does in a good violin.

There have been previous recordings of the opera conducted respectively by John Eliot Gardiner and by Sébastien d’Hérin, but the Gardiner no longer seems to be available on CD (though one can stream it). There was also at least one recording of the overture and a suite of dances. I can hardly imagine any of these predecessors being better than what Plewniak offers us. Apparently the work is given here in its original, most-complete version.

In short, there’s more to Leclair than most of us ever realized. So much for pigeon-holing a composer into just one genre or type of composition!

The booklet gives the full libretto and a comprehensible English translation. Also fine essays on the work and the composer.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is on the editorial board of a recently founded and intentionally wide-ranging open-access periodical: Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal.