Opera Album Review: A Major German Baroque Opera — Reinhard Keiser’s “Ulysses” Gets a Spiffy Recording

By Ralph P. Locke

All in all, an ear-opening introduction to an important opera composer — and to the little-known tradition of German-language (with Italian touches) Baroque opera.

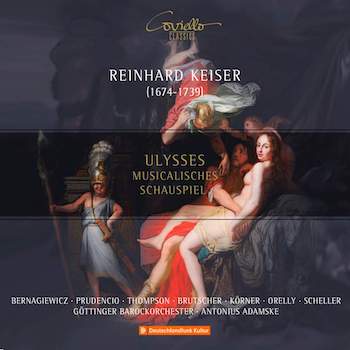

Reinhard Keiser: Ulysses

Bogna Bernagiewicz (Penelope), Francisca Prudencio (Cephalia), Gerald Thompson (Circe), Markus Brutscher (Jupiter), Goetz Philip Koerner (Arpax), Janno Scheller (Neptunus), Jürgen Orelly (Urilas)

Göttinger Barockorchester und -chor, cond. Antonius Adamske

Coviello 92203 [2 CDs] 149 minutes

To purchase or to hear any track, click here.

Most of us know little about German Baroque opera. This is partly because German opera composers around 1700 often set Italian librettos (much as Gluck, Haydn, and Mozart would do, decades later). But it is also because many German-language operas of that era are simply lost, and others have remained unpublished until recently — examples include Telemann’s remarkable Miriways and a no less splendid work that the Boston Early Music Festival has recently brought back to life, Graupner’s Antiochus und Stratonica. In 2005, BEMF revived another early German opera Johann Mattheson’s Boris Goudenow (c. 1710), to critical acclaim, but unfortunately they didn’t record it.

Most of us know little about German Baroque opera. This is partly because German opera composers around 1700 often set Italian librettos (much as Gluck, Haydn, and Mozart would do, decades later). But it is also because many German-language operas of that era are simply lost, and others have remained unpublished until recently — examples include Telemann’s remarkable Miriways and a no less splendid work that the Boston Early Music Festival has recently brought back to life, Graupner’s Antiochus und Stratonica. In 2005, BEMF revived another early German opera Johann Mattheson’s Boris Goudenow (c. 1710), to critical acclaim, but unfortunately they didn’t record it.

So lovers of Baroque music will welcome this new release: the first recording of Ulysses by Reinhard Keiser. Keiser (1674-1739) was the leading figure in the operatic life of Hamburg around 1700. He was Kapellmeister of the orchestra in the large opera theater in the “Goose Market,” and he also directed the theater for a few years, finding ways to interest the town’s increasingly wealthy citizens in this new Italian, yet also cosmopolitan, genre. (Hamburg, an important city-state in the Hanseatic league, was a major center of trade.) Keiser achieved this by setting librettos in German, into which he often interleaved at least a few arias in Italian (by himself or by Italian composers). Handel composed some of his earliest operas for Keiser’s theater (sometimes in a similar mixture of the two languages), then went to Italy for further exposure to current trends in opera and sacred music, before settling in London for the bulk of his career, composing operas in Italian and dramatic oratorios in English.

Alas, many of Keiser’s operas do not survive, but this one does, thanks to its having been written for performance in Copenhagen. It turns out to be a lively and touching product, comparable in style and skill to operas by other composers from around that time, including Stradella (see my review of his Amare e fingere), Alessandro Scarlatti, Vivaldi, and of course the young Handel (see my review of a work composed later in Handel’s career, Agrippina).

The plot involves the return of Ulysses to the long-waiting Penelope, after his having dallied with Circe on his route homeward. There is a second romantic couple (as had long been typical in Italian operas), Cephalia and Eurilochus, as well as a comic servant (Arpax) and several gods. Everything ends happily, after much lovely sighing — and steadfastness — from Penelope.

Conductor Antonius Adamske. Photo: Anton Saecki

Most of the arias, this time, are in German. But some, predictably, are in Italian. One of these, by another composer (Orlandini), is a lovely number in which the nightingale’s nocturnal twittering — expressive of lament and anxiety, in quick succession — is reflected in the florid passagework for the singer and in trills for the transverse flute. That aria is immediately followed in the recording by a potential substitute aria by Keiser himself, on a similar text (but in German). This double dose makes no sense dramatically but does allow us to compare and contrast without having to change CDs and hunt for track numbers. Anybody who doesn’t want to hear one of the two options can simply hit the Forward button.

Act 1 also contains a particularly marvelous “accompagnement furioso” for Circe (invoking Hecate, goddess of the night) to words beginning: “Therefore dash me to pieces, you roiling winds shot through with thunder!”

The singers have light and mostly flexible voices. Several take more than one role (beyond what I show in the header), as is often the case with early-opera recordings made in a studio or (as in this case) in an unstaged performance. (The practice of taking multiple roles is familiar from another genre, oratorio, where there is no need for quick costume changes because there are no costumes!)

Soprano Bogna Bernagiewicz. Photo: courtesy of the artist

A few singers (e.g., Brutscher and Scheller) are not always perfectly on pitch. One (Orelly) cannot reach the frequent low notes that he is assigned. But all the singers are appropriately involved in the text: they put it across, though, in Orelly’s case, this tempts him into huffing and puffing for emphasis.

I particularly enjoyed sopranos Bogna Bernagiewicz (from Poland) and Francisca Prudencio (from Chile) and countertenor Gerald Thompson (from Arkansas), each of them marvelous whether in sustained notes or quick passagework. Thompson has a particularly wide range, from high to low and from soft to full and intense — and he always sounds totally secure. I see that he has won numerous awards, and has performed in recently composed operas as well as early ones (including some Handel at the Met).

The orchestra consists of 21 players — seven violinists among them — plus organ (used mainly for recitatives by the divine characters), harpsichord, and lute. They playing is spirited and accurate, and tempos seem apt, never rushed in the currently fashionable frantic manner. The overture is unusually colorful, containing four trumpet parts (originally staffed by members of the Danish royal trumpet corps). Eight singers are listed in the chorus, but they sound like more: perhaps cast members joined in?

The booklet-essay, by the conductor, is informative but too brief, and was poorly edited. A long 1722 comment from the music critic Johann Mattheson is given in German (again) at the head of the English translation of the essay, and a personal name has been erroneously inserted into the fourth line of that same translated essay, creating nonsense. The sonnet by Telemann about Keiser is likewise given in German twice and not in English.

There are other editorial oddities, such as not mentioning that “Tu che scorgi” is by Orlandini. The word “Daennem.” should have been expanded editorially into the clearer “Daennem[ark].” Annoyingly, no synopsis is included. I found good ones in OxfordMusicOnline.com (i.e., Grove) and in the German-language Wikipedia. (You can run the latter through Google Translate.)

Still, all in all, an ear-opening introduction to an important opera composer — and to the little-known tradition of German-language (with Italian touches) Baroque opera.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is on the advisory editorial board of Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal (open-access). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Antonius Adamske, Coviello, German Baroque, Reinhard Keiser