Book Review: “The Stray Bullet” — William S. Burroughs Discovers His Ugly Spirit in Mexico

Between the heroin, booze, and all else that Mexico had to offer, there was little to no time for William S. Burroughs to appreciate the culture of his adopted home.

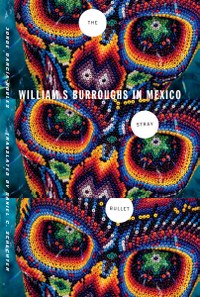

The Stray Bullet: William S Burroughs in Mexico by Jorge García-Robles. Translated from the Spanish by Daniel C. Schechter. University of Minnesota Press, 176 pp., 7 b&w photos. $17.95 paperback.

By Troy Pozirekides

“You won’t make a mistake visiting Mexico … everything I have seen so far has been much to my liking,” wrote William S. Burroughs to Jack Kerouac in 1949. Burroughs had just fled south of the border with his wife Joan and their two young children to avoid standing trial on drug charges in Louisiana. Still years away from publishing the books that would establish him as a major voice of the post-World War II avant-garde, Burroughs delighted in the freedoms of his new home. Mexico City, a place where “anyone who feels like it carries a gun … needles and syringes can be bought anywhere … [and] people simply don’t care what anyone else does,” suited his criminal tendencies and caginess alike.

Burroughs’s years in Mexico, 1949-1952, captured in Jorge García-Robles’ The Stray Bullet (translated from the Spanish by Daniel C. Schechter), a non-fiction account borne out of research and interviews, could be described as tumultuous at best. But García-Robles, a Mexican novelist, critic, and translator of Beat literature, characterizes this time as a necessary, if tempestuous, incubation period. Burroughs enters Mexico as a feckless junky, his only writing “a form of mumbling, an early indication of what would later become a curse.” Within three years, countless episodes of debauchery culminate in the pivotal tragedy of his wife’s death, a “fully dressed Burroughs” emerges “with all his thunder, vision, and spells.” To García-Robles, the time in Mexico enables Burroughs to become the dedicated, if deranged, writer capable of his magnum opus, Naked Lunch.

We see how Burroughs nearly died on several occasions due to his massive appetite for heroin—at its peak requiring three fixes a day. When he wasn’t shooting up, he was drinking, suffering a near-fatal bout of uremic poisoning, which he remedied by switching back to opiates. The casual disregard he displayed for his well-being rubbed off on Joan, whose own dependence on alcohol would turn her pre-existing emotional disturbance into an apparent death wish. And even during rare stints of sobriety, when he was extolling the pseudoscience of William Reich and his theory of orgone accumulation, Burroughs lived lecherously, abandoning his family in pursuit of homosexual flings with boys half his age:

In Mexico, Burroughs slithered silently and inexorably, like a shadow, at the edge of the crowd. El hombre invisible. Neither high nor low culture appealed to him. Not Alfonso Reyes, not Pérez Prado, not Diego Rivera, not Tongolele. Pre-Hispanic culture perhaps, or the lower depths and druggy atmosphere of Mexico City, but nothing else. Burroughs had no Mexican friends, except for the youth that became his occasional lover, Angelo, whom he used to bring to his bachelor apartment at Río Lerma 26, a place that he used for that purpose for a time.

Such sordid affairs should not shock those familiar with Burroughs, however. Part of his appeal to readers lies in their vicarious experience of the worlds depicted in his fiction. He guides us, Virgil-like, into the “lower depths” of various underworlds, from that of heroin addicts in Junky to the disjointed projections of his own mind in Naked Lunch. This makes The Stray Bullet a slightly peculiar volume: those looking for an exposé of Burroughs’s secrets will be disappointed since most of the material from this time period has been covered by the author himself, either in his novels or in his published letters. García-Robles uses his cultural perspective to contextualize Burroughs’s Mexican experience within that of other American expatriate and Mexican writers of the 1950s. But we soon find that Burroughs’s experience was atypical:

More than arriving in Mexico, William Seward Burroughs was running from the USA … the major motivation behind [his] residence in Mexico was not Mexico but Burroughs. The fact is that Burroughs could be somewhere without being there at all. He could breathe the air of a country without breathing it.

Between the heroin, booze, and all else that Mexico had to offer, there was little to no time for Burroughs to appreciate the culture of his adopted home. García-Robles rightfully focuses on the handful of fellow miscreants who captivated the burgeoning writer. These colorful individuals, from silver-tongued lawyer Bernabé Jurado to matronly drug czar Lola La Chata, would eventually inspire characters in works such as Junky and Queer. But the most significant person to Burroughs’s Mexican experience was undoubtedly his troubled wife, Joan Vollmer Burroughs.

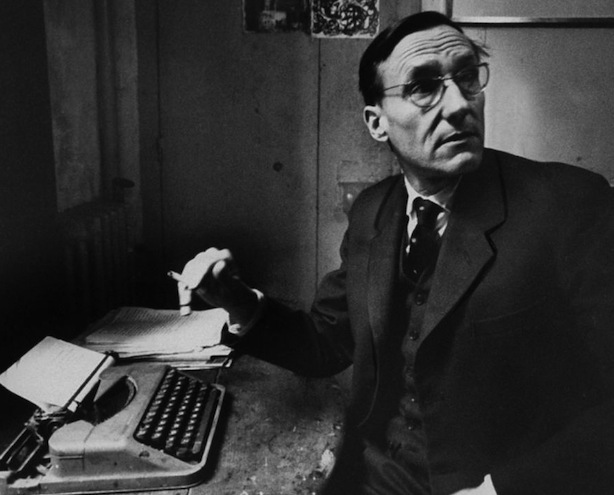

William S. Burroughs — the author eventually came to believe that the same uncontrollable force that drove him to kill his wife also inspired his writing.

Joan was already an alcoholic by the time she got to Mexico with her husband and kids. The couple would fight over their mutual sordid proclivities, often violently. As one would imagine, given that the bulk of Burroughs’s days were taken up with scoring drugs and writing, “sexual intimacy between them was nonexistent.” But the two shared a unique, near-telepathic bond, demonstrated by a parlor game they would put on for friends:

Joan sat in one corner of the room, Bill in another. Each took out a sheet of paper and pencil and drew a box divided into nine equal squares. In each square, they drew an image, and when they’d finished they compared their work. The results were startling. More than half the images matched. Between Joan and Bill … there was a special, profound degree of communication guided by the power that Joan exerted over Bill. She was the transmitter, he the receiver.

Their profound qualities of communication and trust would culminate in the defining moment of Burroughs’s Mexican experience. In what could be seen as a violent variation on their parlor game, Burroughs accidentally shot and killed Joan. García-Robles provides a perceptive exegesis of the events in the immediate aftermath of the killing. He utilizes excerpts from letters and unpublished interviews to demonstrate that it was Joan’s death that transformed Burroughs into a real writer. The author eventually came to believe that the same uncontrollable force that drove him to kill his wife also inspired his writing:

The death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.

García-Robles’ perceptive grasp of Burroughs’s complex relationship with his wife, and its influence on his writing career, makes The Stray Bullet worth reading for someone already well-versed in Burroughs’s story. It is insightful, but not groundbreaking, thanks largely to the extant works on the same subject matter, from Burroughs’s novels and Yage Letters to Jack Kerouac’s Tristessa and Desolation Angels. The attention to Joan Vollmer’s influence on Burroughs should be appreciated because the writer rarely depicted his wife in his own novels. But García-Robles, in his efforts to capture the entire scope of Burroughs’s Mexican experience, never delves deeply enough to make The Stray Bullet more than supplementary reading. An in-depth study that fully exorcises Burroughs’s “Ugly Spirit” is perhaps still needed.

Troy Pozirekides is a writer, critic, and editor. Currently a senior at Boston University, he specializes in British and American literature of the twentieth century, from the poetry of Philip Larkin to the works of Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation. Troy is also a musician and jazz aficionado, playing trumpet and guitar. Follow him on Twitter at @tpozirekides.

Tagged: Beat literature, The Stray Bullet: William S Burroughs in Mexico, Troy Pozirekides