Book Review: “The Goddess Chronicle” — Needs Less Plot, More Imagination

There is a paucity of richness in The Goddess Chronicle. The myth might have been, but wasn’t, mined for tales of compassion, or inevitability of sorrow, or the psychology of misogyny or of revenge, or the strictures of fate.

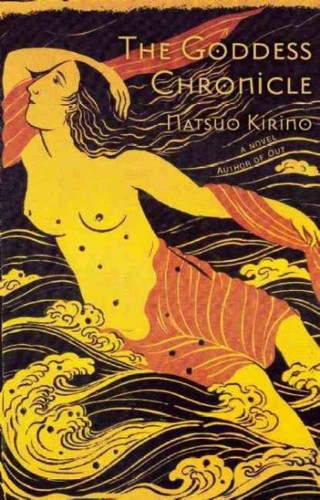

The Goddess Chronicle by Natsuo Kirino. Rebecca Copeland, translator. Canongate U.S., 320 pages, $24.

By Marcia Karp

Canongate Books, publisher of The Goddess Chronicle, began its Myth Series—“A bold re-telling of legendary tales by the world’s finest contemporary writers”—in 1999. Its website says that each of its writers has “retold a myth in a contemporary and memorable way.” Natsuo Kirino, author of the latest volume in the series, has been certified fine by the awarding bodies of international prizes for crime fiction, she is alive now, and retells part of the Shinto creation myth. While her retelling can at times squeak by as a contemporary idiom, what is memorable about the novel is how little it illuminates its original and how little the legend enriches the new work, which is often dead and more often flat.

The legend is about Shinto’s kami (gods or forces of nature) responsible for creating the land and its creatures and phenomena. Izanaki (spelled elsewhere as Izanagi) and Izanami have their particular characteristics and history, while sharing with deities in other traditions an apprenticeship that requires a starting over. It can be comforting to the humans who care about these stories that their gods are subject to the sorts of disasters, or even just mistakes, that human life is full of. This couple is human in other ways, for the two seemed to be doomed from the start and are violent, weak-kneed, and vindictive.

Once they notice their bodies differ, Izanaki has an idea. Kirino has Izanami recount it this way:

‘“Let me put my place of excess into your place of emptiness, and thereby fill it. In this way I should like us to give birth to the land. What say you?” And I agreed.’

What say you? Now there is a proposition.

Some version of archaized speech is used for all the voices in the novel: the narrator’s, her quotation, her quotation of someone’s quoting, as here. When the kami act on the passed motion, Izanami breaks the rules she wasn’t aware of by being the first to flatter the other. The result is the birth of a “limp and squashy” Leech-child. He’s set adrift to starve and drown, the rules are learned, and there are lots of births: the various islands that become Japan and kami of elements and places. Then Izanami is burnt as she gave birth to the Fire God, Kagutsuchi, but she keeping on creating. She vomits the Mining Gods into life. She shits the Gods of Clay and pisses those of Gushing-Waters. There is even more apt fecundity, but eventually she dies of her burns. Equally talented, Izanaki weeps a god into being, kills Kagutsuchi, and begets others from the blood of his son as it drips off the murderous sword. Kirino makes sure her reader doesn’t miss the consequent upgrade to the weapon:

Fire and the sword have an inseparable connection, do they not? The sword is born from fire, and the right to fire is controlled by the sword. Thus, the birth that took Izanami-sama’s life delivered the new controlling force of the sword.

This is a characteristic extraneous and dull didacticism. Here and elsewhere, what is missing is an imagination that lives inside the myth. Kirino doesn’t wonder how it is that fire still exists. She doesn’t consider that Kagutsuchi had no say in his essence. She doesn’t write from the twenty-first century: Thus, the birth that took . . . . Nor does she (or perhaps her translator) always create a coherent language. Here is the storyteller, Hieda No Are, as she relates the damage done to Izanami:

By that I mean, of course, that giving birth is dangerous—it can easily take one’s life. And so it was that tragedy struck one day. [. . .] her female parts were badly burnt.

She moves from contemporary semi-formality to coercion (of course), then to sober platitude, and so to the flourish that so often in the novel provides drama rather than dramatization, ending in a prudish, old-fashioned non-naming of parts.

Once he’s killed Kagutsuchi, Izanaki travels to the darkest darkness of the Realm of the Dead to find his beloved. She tells him she can’t leave because (like the earlier Persephone) she has eaten food there but that he must be patient and she will work things out. Above all else, he must not look at her. Does he listen? A god like that, who’d kill his own son? Ha!

He shines a light upon her decaying body and is disgusted. Rage and a chase; a heavy boulder to seal her away; and a shouted Hi Ho Sister (I mean, of course, We are divorced). Then she, in fury, kills 1000 people each day forever. Limited in the same way the Greek gods were, he can’t prevent what she decrees, so he responds with his own daily responsibility—the birth of 1500 children.

When the dull exposition of this myth has gone on so long that even the author realizes it is too much, Kirino tries to bring the thing to life by ginned-up excitement.

‘That’s enough!’ Izanami interrupted.

Hieda no Are looked up at her and released a long sigh. For the first time she noticed that her monologue had put Izanami in a bad mood.

You might expect that the bad mood will become manifest, but the tale continues in the same voice, only now without quotation marks, as if Hieda no Are is replaced by a spirit even more disembodied than the usual ones in the Underworld.

Kirino has placed her own creations in contact with the mythic ones. Namima, the book’s narrator and her sister, Kamikuu, live in dire circumstances. They are fated to serve the forces that rule their miserable, teardrop-shaped island, which inexplicably goes from a- to nonymous over the course of a paragraph:

Our island has no particular name. We always referred to it simply as ‘the island.’ But when our menfolk were out on the seas, fishing, occasionally they’d come across men in other vessels who would ask them where they came from. It was their custom to respond, ‘From Umihebi, the island of sea snakes.’ I heard that as soon as they said as much the men on the other boats would lower their heads in a gesture of respect. Our island was known far and wide [. . .]. Even the few people who lived on small, remote islands had heard of Umihebi.

Though at the top of the island’s hierarchy—the family was the Umihebi clan—the sisters are as trapped by its poverty as anyone else there and trapped, even more so than the others, by the local customs. Even Kamikuu, who as Oracle-in-training is given the most and the best food, has it hard. Yet, the others, including the younger sister who had to walk miles everyday with the basket full of aromatic secrets, might not have enough of even the poor diet that custom condemn them to. Kamikuu, sent to live with the current Oracle on her sixth birthday, tries to share the food with Namima. But the dutiful sister won’t break the law. She mustn’t look inside the basket, nevermind eat from it, so every night she carries the basket to the cliff and feeds what remains into the sea.

Years pass and rebellion arrives with Mahito, son in an outcast family— he has no sisters, though his mother is obligated to produce one who will be the insurance Oracle in case Namima’s family lets down the culture. (Namima can’t serve in that capacity. She is yin to Kamikuu’s yang. Soon we’ll see what’s in store for her.) Mahito persuaded the faithful girl into defiance—they eat from Kamikuu’s leftovers, and he takes the rest home to his mother, so as to stop her from bearing only boys.

I’m sorry to be droning on with the plot, but there is little else in the novel. It’s all surface, written or translated, or both, in Catullus’s non bona dicta—not good words.

Mahito’s mother was now nearing forty. Pregnancy at her age was as dangerous as it was necessary.

There is no justification for the didacticism of Namima, unless it is that she is not a character, but a mouthpiece for the author. In any event, no girl was born to redeem the outcasts; instead, there was forbidden love:

Two months earlier, Mahito and I had begun to enjoy the ways of the flesh.

This is simultaneously prudish and ripped from the bodice, I mean, pages of old dime-store novels. It is also important to the plot.

Balance, not compassion, is the island’s motivating principle. The day Kamikuu replaces her grandmother as Oracle, Namima learns that her sister’s realm of Light is in opposition with what is to be her own, that of Darkness. Her life is sacrificed to the company of the corpses of the island’s dead and must, upon the death of the Oracle, do her duty and die on the spot. But the ways of the flesh have taken root in her, and she is pregnant. For her, too, this was a danger, since only the keeper of the Light could bear children to their family. What to do?

I’ll bet you can guess. There is an implausible, but daring, escape with Mahito, weeks at sea, the birth of a daughter, and (believe me, this is not a spoiler) Namima is murdered.

Now, she encounters the goddess of the title, the kami Izanami. She hears the creation myth. She serves the goddess. She returns to Umihebi, embodied as a wasp, and discovers what Mahito was up to from the start. She even manages to affect his life. Then comes the story of an attractive man and his burden of immortality. There is no change of narrator, though it makes no sense that Namima knows any of this or what he felt or what he told himself. Threads are drawn together, and we return to the Underworld. Mahito makes a visit, as does Izanaki. Namima tries to be brutal and can’t be; Izanami vows to never be less than brutal.

The moral of the story is given by Namima who explains why she can at least admire, if not emulate, the goddess she serves:

For, as I said earlier, Izanami is without doubt a woman among women. The trials that she has borne are the trials all women must face.

There is a paucity of richness in The Goddess Chronicle. The myth might have been mined for tales of compassion, or inevitability of sorrow, or the psychology of misogyny or of revenge, or the strictures of fate. Instead, it uses imagination in the service of plot points only and does not point beyond its surface. There is some compelling language—the section titles: “Today, This Very Day,” “With All I Do in this World,” “How Comely Now the Woman,” and “How Comely Now the Man”—that holds out an unfulfilled promise.

The Ice Maiden: she is one of three children sacrificed by the Inca. Their remains are considered the world’s best preserved mummies.

If you like myths and legends and primal tales, I recommend these: Maria Tatar’s versions of folk tales; Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, with stories that are motivated by something essential in those tales; Rosanna Warren’s poem “Eskimo Mother,” which imagines a truth about child sacrifice when done for the immediate good of the group; and this summer’s news stories on the tests carried out on the Argentinian mummies of children sacrificed by the Incas for reasons that might range from celebration to propitiation to tradition. Or go to book two of Paradise Lost, beginning around line 750, where Sin brings forth Death in the same way Izanami delivers the Gods of Clay. We feel so much from Milton, and nothing at all from Kirino. Translation is the convenient demon, but it won’t do to put the blame there. Even a teeny bit of imaginative living inside her characters would have helped Kirino bring life to her re-telling. Plot isn’t enough.

Marcia Karp has poems and translations in Free Inquiry, Oxford Magazine, The Times Literary Supplement, The Warwick Review, Ploughshares, Harvard Review, Agenda, Literary Imagination, Seneca Review, The Guardian, The Republic of Letters, and Partisan Review. Her work is included in these anthologies: Penguin Books’ Catullus in English and Petrarch in English; Joining Music with Reason: 34 Poets, British and American, Oxford 2004-2009 (Waywiser); and The Word Exchange: Anglo-Saxon Poems in Translation (Norton).

Tagged: Canongate Books, Marcia Karp, Myth, Natsuo Kirino