Stage Commentary: The Need for a Theater of Transformation

Theater taught me how to draw parallels, to condense, to delete triviality, and to recognize significance.

By Robert Israel

Several years ago, I attended a production by the feminist troupe At the Foot of the Mountain on the political ramifications of rape. The director, Martha Boesing, took a bold approach: she invited audiences to a community center in Minneapolis, Minnesota where they were instructed to interrupt the actresses at any time if they felt compelled to share their personal stories. The night I attended, several women stood up and proclaimed, “Stop!” The actresses, onstage and in character, froze in mid-scene. The testimonies that followed were chilling and horrific; the play’s political message was personalized.

Some theater critics likened the production to psychodrama; several others complained it was like eavesdropping at a therapy session. Boesing dismissed these comments as callow, crass.

“Theater is about catharsis,” Boesing told me during an interview. “We learned that in Drama 101. But, for me, that’s not enough. That’s why I chose to present the play in the Powder Horn neighborhood, in the community center. It’s all about accessibility. Audiences need to see theater where they live; they need to be encouraged to express their deepest feelings and to be moved to act on those feelings, which I see as an essential part of the dramatic product.”

As a teenager in the late 1960s, I experienced assaultive theater productions when my public school classmates and I were bused to see Trinity Repertory Company perform in Providence, Rhode Island. I credit those productions with awakening in me a lifelong appreciation for acting, storytelling, and stage craft. But there was another reason: coming of age during Vietnam, I was convinced I’d end up fighting in a war overseas like my father, a World War II veteran. I clung to theater to keep me inspired during those turbulent times.

I was not disappointed. When I attended a Trinity Repertory production of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, I discovered that the play mirrored the conflagrations that erupted nightly as American soldiers were televised wading through rice paddies in Vietnam. The Trinity Rep actors—who moved freely through the auditorium, bringing the action of the play not only in front of the faces but sometimes onto the laps of audience members—wore resplendent Roman robes, but they might have well have been wearing Army fatigues. When Caesar was surrounded by actors brandishing long knives, it was as if the assassins onstage were carrying bayonets like the Army grunts I watched on television jabbing into clumps of jungle where suspected Viet Cong were hiding.

Theater taught me how to draw parallels, to condense, to delete triviality, and to recognize significance. This process helped me to decipher the complexities around me. Theater also affirmed that there was no such thing as pre-determined paths, a forced march toward fate. I was evolving through my thoughts and actions, like the characters whose lives unfolded onstage. I could reject or accept what others dictated and face the consequences of my actions. I was free to develop into my own person, become an individual.

***

Two playwrights, Robert Lepage and Bill Cain create works of theatrical transformation. Both present characters who shape-shift before audiences’ eyes. Their works encourage us to reflect on our own constantly morphing lives, on the zig-zagging stages of our development.

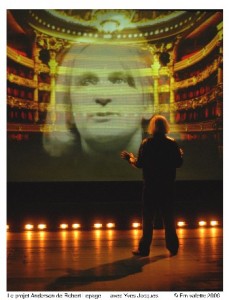

Lepage, who hails from Quebec City, Canada, is the creator and director of the Cirque du Soleil show Ka and The Andersen Project; both shows have toured internationally.

In Ka, Lepage’s slimy characters “gyre and gimble” (Lewis Carroll’s description of writhing lizards in “Jabberwocky”) on a large, green, rubbery orb, center stage. Soon they transform into humans, clothed in multicolored Spandex outfits. Ropes are lowered; they are hoisted above our heads to perform astonishing feats of acrobatic prowess. He used similar techniques in his staging of Wagner’s Ring Cycle at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

In The Andersen Project, a solo character, played by Canadian actor Yves Jacques, goes through so many transformations one scarcely could count them. In addition to taking on multiple roles, Jacques bumbles his way through the streets of Paris buffeted by strange encounters (including a scene that takes place in a seedy porno booth). His journey mirrors a story, written by Hans Christian Andersen, he is contracted to adapt, but never completes, for the Paris Opera.

Lepage, who recently received the McDermott Award from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, defines theatre as an art form that takes us back to when our ancestors stood around fires to tell stories and used shadows to suggest other characters, other voices, other locales. Lepage claims this primal “technology” (projecting images through light and heat) gave birth to all the technologies that followed. Transformation, he says, is part and parcel of who we are; we are always evolving; we never know what we will ultimately become. The Cirque du Soleil show uses technology not only via computerized images but through the manipulation of music, light, and other electronic sound effects. The Andersen Project also makes ample use of these technologies to picture imaginative potential. It is not by accident that, while Jacques takes his bows before the final curtain, the last image projected on the screen onstage is of a computer-generated blazing inferno.

Without this ancient art of shadow dancing, and its unconscious invocation of a primitive campfire, Jacques, the solo actor, could not weave his mysteries. At the play’s end, Jacques has survived one hallucination after another. He stands shaken, changed, but most determinedly human; he will survive whatever life has in store for him.

**

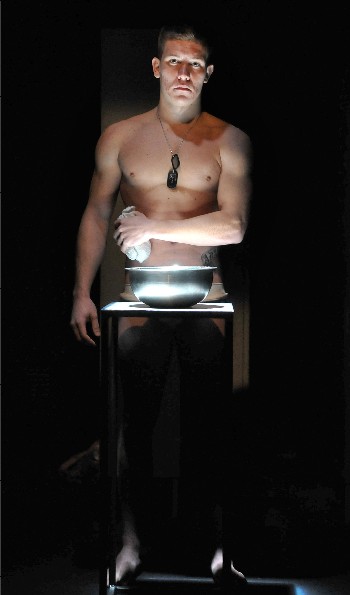

American soldier Daniel Reeves (Jimi Stanton) in the Publick Theater production of “9 Circles.” Photo: Craig Bailey/Perspective Photo

Playwright Bill Cain, a Jesuit priest, was the founder and director of the now defunct Boston Shakespeare Company. Cain, like Lepage, views our struggles to attain humanity as a journey of transformation in a world often indifferent (even hostile) to our quests.

“One of my first experiences in theater,” Cain said recently, “was when a group of us went to perform at the leukemia ward at Children’s Hospital in Boston. In the face of this terrible disease, in the face of leukemia, our performance made people human. Something happened . . . it is the presence of God. It is not a metaphor. This event, which erases differences, introduces us into something larger, and I knew then that I needed to do this for a lifetime.”

One of Cain’s most recent plays is a one-act, 9 Circles. Director Eric C. Engel gave the script its East Coast premiere at the Publick Theatre in Boston in 2011—later re-staging it with the Gloucester (Massachusetts) Stage Company in 2012 with the same cast of three actors who play multiple roles. In his staging, he wanted to emphasize the play’s “linear and accessible” format. The script is based on the case of former 101st Airborne Division Pfc. Steven Dale Green, convicted in a federal court in 2009 of raping and killing an Iraqi 14-year-old girl and murdering her family. Modeled after the nine “circles” of Dante’s Nine Rings of Hell, we learn of fictional character Pvt. Reeves’s atrocities, subsequent punishment, and execution by lethal injection.

“It’s not so much a play about war,” Engel said, “but about one man’s personal salvation. Cain’s play strips the character of Pvt. Reeves bare. The protagonist is depicted as man stripped naked—physically, psychologically, and psychically. The playwright’s aim is to give audiences “an experience where you see, feel and hear people to their very core.”

Indeed, at one point in the play, Reeves stands naked onstage while engaged in a ritual act of cleansing himself, which calls to mind a discussion he had with a priest earlier in the play about baptism. Before the final curtain, the character delivers a 7-minute monologue. It is spoken in staccato, snippets of previously heard speeches, gnarled words sputtered by a slowly dying mind while the man’s body—absorbing the lethal injection—twitches and becomes still. During this scene, Reeves is bathed in a bright light.

Cain, in a note to the 9 Circles script, wrote, “As the intensity of the light grew, the moment became a transfiguration.” Indeed, the character of Pvt. Reeves, having been through the nine circles of personal and public hell, arrives at the play’s finish having achieved transformation, or, in his case, redemption.

9 Circles has had subsequent productions in Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Denver. It was awarded the Harold and Mimi Steinberg/America Theatre Critics Association New Play Award, presented for the best scripts that premiered professionally outside New York City.

For Cain, choosing to transform your life is hard work. “Faith and God are easy,” he has said, “it’s believing that you matter that is very, very hard.”

**

Not all theatrical productions are transformative. I often go to shows for the sheer delectation I derive from being entertained by players whose talents explode onstage in joyous spectacles.

But if I’m trying to get at those “deepest feelings” director Martha Boesing sought to elicit when she was creating her fierce and provocative production, I know I have to look elsewhere. I turn to plays by Bill Cain or Robert Lepage and to others like them, knowing, after the final curtain, I will be pushed out the door and encouraged to pursue life-altering paths.

Robert Israel, an Arts Fuse contributor since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

Tagged: 9 Circles, Bill Cain, Martha Boseing, Robert Lepage, The Andersen Project