Theater Review: A Pair of Dostoevskian Inquisitions

Dostoevsky’s theater is set on a metaphysical stage–both The Grand Inquisitor and 9 Circles explore whether the actions of their central characters are meaningful or absurd.

9 Circles by Bill Cain. Directed by Eric Engel. Staged by the Publick Theatre at the Boston Center for the Arts, Plaza Theatre, through April 9.

The Grand Inquisitor in the The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky. Adapted by Marie-Hélène Estienne. Directed by Peter Brook. ArtsEmerson presents the Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord production at the Paramount Theater, Boston, MA, through April 3.

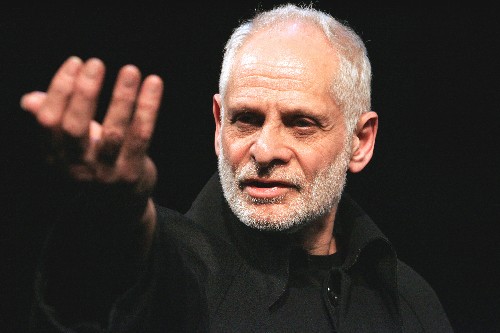

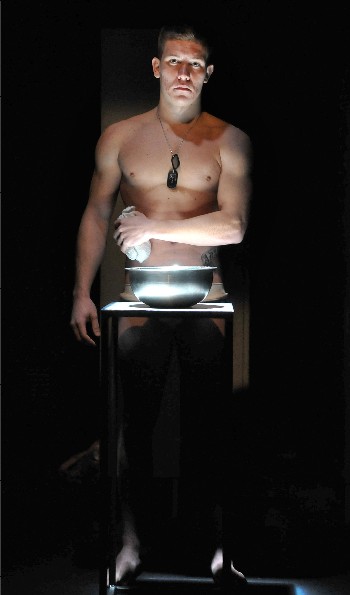

Updated Dostoevskian Drama: American soldier Daniel Reeves (Jimi Stanton) in 9 CIRCLES. Photo: Craig Bailey/Perspective Photo

By Bill Marx

Is there anyone who wrote better about hell on our secular earth than Dostoevsky? A writer has to believe in the evil the soul is capable of to describe how it writhes in pain, the flames of damnation licking at its heels. Part of the Russian novelist’s enduring genius is his ability to imagine the decadent flip side of his religious sensibility, the photo negative of the saintly. Few authors have so concretely described and then ironically savored the death of God and the rise of the Devil, the latter championing a secular world increasingly drunk on a freedom bereft of value and direction. The extinction of the transcendent means the end of meaningful human action–choice becomes relative. Dostoevsky’s theater is set on a metaphysical stage–both The Grand Inquisitor and 9 Circles (winner of this year’s Harold and Mimi Steinberg/ATCA New Play Award) explore whether the actions of their central characters are meaningful or absurd.

Of course, the chapter in The Brothers Karamazov is a masterpiece: Christ comes back to earth at the time of the Spanish Inquisition, is soon imprisoned, and is told by an aged cardinal Grand Inquisitor at great length that the Savior isn’t wanted a second time around. His vision of morality and peace is too difficult for the masses, who want to be led rather than challenged, to be beaten rather than liberated. A number of interpretations are possible; for me, it remains a magnificent allegory about how easily we give up independence of thought and action, swapping moral action for the pragmatic gods of safety and conformity. We desire tyranny and bullies, argues the Grand Inquisitor, because it feds our appetite for violence and stasis. A minority of the ‘elect’ may demand liberation from servility, but they are marginal.

Why go to a performance of the text rather than read it? The approach of the actor should illuminate the work in fresh ways, to make you think carefully through Dostoevsky’s arguments rather than give them a dutiful listening. Though Bruce Myers, as the Grand Inquisitor, glances down at his script throughout his performance (in a post-show discussion, he said the demanding part had become impossible to remember), the aid only adds to the poignancy and intellectual sting of his performance, which makes the elderly Inquisitor a complex character, far more sympathetic than he is on the page.

At times tentative about his servile creed, at other times resolute about the need to privilege survival over liberation, Myers’s Inquisitor is an uncertain performer, trying to convince himself and Christ that he is in the right. Perhaps there are no fireworks in this earnest rendition of the text, but the human element and Myers’s skill with vocal dynamics add resonance to a story that remains radical.

Dostoevsky feels free to whisper subversion; alas, we need to shout it. In Bill Cain’s compelling (based on actual events) if sometimes irritatingly strident play, 9 Circles generates a contemporary version of a soul in torment, building an intense drama around an American solider (from a poor, dysfunctional family in Texas) bedeviled by an incident of horrific violence committed against civilians during the Iraq War. At first glance, the plot looks like a nervy political or psychological thriller, a sort of who- or why-dun-it, with a number of ambiguities raised about the actions of Daniel Edward Reeves: did he commit heinous acts against the innocent or is he a scapegoat for the crimes of others or for the sins of corrupt institutions?

Once he is charged with war crimes, Reeves faces a series of contemporary inquisitors. Throughout his ordeal, he belligerently insists he has no regrets for what he did and is wary of any offers for help or understanding. He was in Iraq to kill, and that is what he did. The questioners range from lawyers who want to assist Reeves as a way to embarrass the American military, a psychologist uncomfortable about what Reeves has learned, and a Catholic cleric who wonders if Reeves is evil or not.

The interrogations are emotionally overloaded, often striking a high note and then sticking–I am not sure if we are to view this relentless parade of legal, therapeutic, and religious questioners as realistic figures or as demonic caricatures filtered through the disturbed mindset of Reeves. Ultimately, the locale of 9 Circles is the hell of secular rationalizations, our weakness for finding legal rationalizations to explain enigmatic choices: to his credit, Cain memorably brings Reeves right up to the “hot gates,” with confession raising the possibility of grace or damnation.

The Publick Theatre’s powerful though exhausting production of the East Coast premiere the play cannot be faulted. Director Eric Engel and his solid cast pump up the emotional temperature, each scene between Reeves and his tormentors crackling with hostility, calculation, black humor, inscrutability, and a sense of futility. Jimi Stanton brings a little boy surliness to Reeves–like the Grand Inquisitor, the lost soldier seems to be acting out a role because he cannot accept the absurdity of what he believes to be the truth, to admit the moral responsibility of empathy. Playing a series of roles, Will McGarrahan skirts but generally escapes cartoonishness, while Amanda Collins handles her collection of characters with no-nonsense dispatch.

Still, as well performed, lit, and staged as it is, 9 Circles feels it must grip us by the throat and shake us to make us think about the religious questions it asks about the inequities of contemporary society. Overanxious about the patience of audiences in the age of New Media, contemporary theater seems to be divided into visual extravaganzas or visceral-to-the-max rampages, the latter the result of fears that if the shocks end, viewers will hit the mental remote control. The irony is that the evening’s unforgettable moment, its coup de théâtre, arrives when Cain presents us with the still voice of humanity hovering at the end of its tether, an indelible image of the quiet hell that comes once one faces the truth about one’s self. Dostoevsky would have approved.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: 9 Circles, Bill Cain, Boston, Bruce Myers, Peter Brook, Publick-Theatre