Popular Music Review: Light and Darkness in The National

Perhaps independent music’s biggest “it” band right now, The National have recently released their fifth album, and appear on the brink of crossing the threshold from well-kept secret to mainstream sensation, if their recent back-to-back sold out shows at Boston’s House of Blues are any indication.

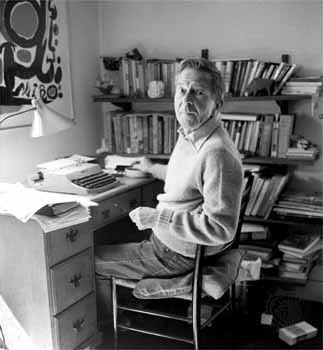

The National: The group's music contains echoes of the suburban angst evoked by writer John Cheever.

By Justin Marble

In college, I took a comparative literature course where one of our assigned authors was John Cheever. Cheever’s short stories are famously dark descents into American suburbia: the chips in the white-picket fence, the mole in the rose bushes, the emotional outburst once all the friends have left. He examined the tensions lying just underneath the surface of the idyllic 1950’s Leave It To Beaver images. Cheever the man had his own well-publicized dealings with these demons, including bouts of alcoholism, accusations of bisexuality, and a crippling depression related to his deteriorating marriage.

After delving into our first Cheever stories, like “Goodbye, My Brother,” the story of a family vacation that ends with one brother brutally assaulting the other, our professor asked us to characterize the tone of his work. “Gloomy,” “mopey,” “melancholy,” “depressing,” and “dark” were about the range of the answers. While agreeing with us, the teacher then turned our attention to a number of passages that were completely the opposite. Hiding in plain sight in Cheever’s stories are lengthy descriptions of unmistakable beauty and moments of tenderness that almost all of us had overlooked.

His point was that darkness overshadows light, but the best artists use both. I can’t help but hear echoes of Cheever in the music of Brooklyn-based indie band The National. The band built their indie cred with highly publicized opening gigs for REM and Radiohead and the use of their song “Fake Empire” in Barack Obama’s campaign.

Perhaps independent music’s biggest “it” band right now, The National have recently released their fifth album, High Violet, and appear on the brink of crossing the threshold from well-kept secret to mainstream sensation, if their recent back-to-back sold out shows at Boston’s House of Blues are any indication.

Author John Cheever: He paved the dark suburban street for The National.

While they are certainly critical darlings, like Cheever, they’ve had their fair share of detractors who say their lyrics are too pretentious, they take themselves too seriously, and that their songs are too dark and depressing. All true, to a certain extent. But much like me and my classmates misreading of many of Cheever’s stories, The National’s albums are actually a balancing act between light and darkness, written by artists who alternate between misery and jubilation.

The National’s 2007 fourth album, Boxer, is Cheever in MP3 form. The album’s name is pugilistic, and the songs are essentially about twenty-somethings fighting against the world. Nothing particularly new, but then, neither was Cheever. What sets them apart is the execution.

Like Tom Waits, lead singer Matt Berninger tends to speak his lyrics rather than sing them, giving their work a literary quality. His deep baritone keeps things muted and restrained even though his lyrics offer a crippling fear of the adult world. Whether it’s lines like “half-awake in a fake empire,” “we expected something more,” or “make up something to believe in your heart of hearts so you have something to wear on your sleeve of sleeves,” the tone is one of searching for something, anything, to hang your hat on. The album ends with Berninger repeatedly and understatedly proclaiming “killers are calling on me.”

If you listened to the album after reading a story like Cheever’s “The Swimmer,” where a suburban man suddenly decides to swim through his neighbor’s pools in an effort to prove his worth, you might think that we haven’t progressed much in the near half-century between the two works. Perhaps not—perhaps these feelings are part of the human condition.

High Violet finds the newly-minted adults of Boxer trying to accept the fact that their actions and decisions now have consequences on the people around them. The tone might best be encapsulated in the line “with my kid on my shoulders, I try / not to hurt anybody I like.” The answer to the searching and questioning tone of Boxer may lie in family and relationships. On the track “Afraid of Everyone,” Berninger croons “I defend my family/with my orange umbrella/cause I’m afraid of everyone.”

This is something Cheever could never quite get to, and it appears The National has trouble as well. There is a sense of desperation to the works. Both want to be good fathers, good husbands, good people. Their self-destructive nature is the source of their despair. The track “Runaway” deals with this directly: “there’s no saving anything,” and “we’ve got another thing coming undone,” are oft-repeated refrains.

If this all sounds gloomy and melancholy, it is. Yet The National’s music also infused with beauty and hope, which sets it apart from the pretenders. Cheever would frequently detach from the plot of his stories in order to describe a beautiful sunset or nature, as if to remind the reader that beyond all of this despair there is something worth living and trying for. The National’s version of these asides lie in the actual music beneath the lyrics. Berninger is flanked by two pairs of brothers: the guitar-playing and classically-trained twins Aaron and Bryce Dessner and Scott and Bryan Devendorf, the bassist and drummer. Even at its most darkest, and really, it doesn’t get much darker than “I was afraid I’d eat your brains/cause I’m evil,” the band balances it with the underlying music. As Berninger’s deep voice methodically sings those lyrics, the rest of the band breaks into high-pitched backing vocals that can’t really be described as anything other than an angelic chorus.

When they play live, The National bring two horn players and a violinist/keyboardist. Not only does this make their live shows considerably more epic than their albums, but it gives the songs a triumphant quality underneath the despair. The vocals are the centerpiece of every song, so the actual music is never dominating, but the band uses it brilliantly. Beyond their staggering technical ability, The National know how to use music to say things that can’t be said, and that is a musical talent that simply can’t be taught.

That’s not to say there aren’t positives in the lyrics. Amid all the darkness lie refrains like “you know I dreamt about you/for 29 years before I saw you,” and “you’re the only thing I ever want anymore.” Berninger explicitly states “I want to believe in everything you believe.” Cheever shies away from talking about love, but it’s at the forefront of The National’s music. This isn’t Disney love, but they are earnest and honest in trying to make it work. The opening track of High Violet, in fact, is “Terrible Love,” which might just be the most efficient way to sum up the band.

The goal of art is truth. Too often, the films that are championed and the music that is celebrated are “feel-good,” and anything that doesn’t have a happy ending is “dark.” This isn’t a defense of emo music: saying all is lost and everything is bad is just as disingenuous as pretending the world is perfect. The true artists realize that good and evil, light and dark, happiness and sadness cannot exist without each other. Reading Cheever or listening to the National is a journey into darkness, but it makes the small moments of light all the more rewarding.

Tagged: High Violet, House of Blues, indie rock, John Cheever, Justin Marble, suburban