Opera Album Review: Baroque Music Enlivens the Boston Music Scene and Two New French Recordings

By Ralph P. Locke

The Boston Early Music Festival announces its 2024-25 season, and our critic welcomes world-premiere recordings of operas by Mondonville and Destouches, splendidly sung and glitteringly played.

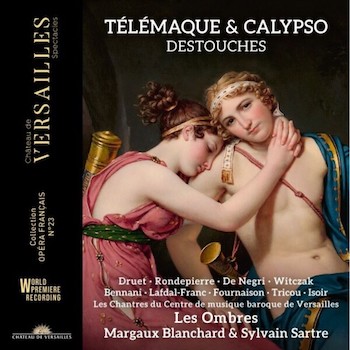

DESTOUCHES: Télémaque et Calypso

Isabelle Druet, Emmanuelle de Negri, Hasnaa Bennani, Antoni Rondepierre, David Witczak, Adrien Fournaison

Les Ombres, cond. Margaux Blanchard and Sylvain Sartre.

Versailles Spectacles 128 [2 CDs] 126 minutes.

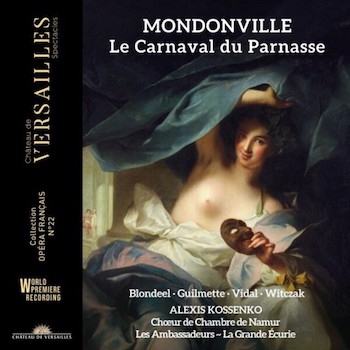

MONDONVILLE: Le Carnaval du Parnasse

Gwendoline Blondeel, Hélène Guilmette, Hasnaa Bennani, Mathias Vidal, David Witczak, Adrien Fournaison.

Les Ambassadeurs, La Grande Ecurie, cond. Alexis Kossenko.

Versailles Spectacles CVS122 [2 CDs] 128 minutes.

The Boston Early Music Festival has announced its 2024-25 season, including its renowned summer festival (8-15 June 2025). The rich summer offerings include two short operas by Telemann, one of which, Ino, I recently discussed here, thanks to a splendid new recording from the Akademie für Alte Musik, Berlin. As for the “concert season” (the offerings between now and the summer festival), it turns out to be full of Italian and German works, including a fascinating concert in which the texts that Brahms used in his German Requiem — one of the established masterpieces of the choral repertory — will be presented in settings by Baroque-era composers! There’s even a concert that features renowned countertenor Reginald Mobley and consists of music by Baroque-era composers from the New World, some of whom were from previously enslaved families of African origin. Even better, the events during the 2024-25 concert season (though perhaps not those during the June 2025 summer Festival) are being made available in a videostreamed version as well—great news for those of us who live far from New England.

The Boston Early Music Festival has announced its 2024-25 season, including its renowned summer festival (8-15 June 2025). The rich summer offerings include two short operas by Telemann, one of which, Ino, I recently discussed here, thanks to a splendid new recording from the Akademie für Alte Musik, Berlin. As for the “concert season” (the offerings between now and the summer festival), it turns out to be full of Italian and German works, including a fascinating concert in which the texts that Brahms used in his German Requiem — one of the established masterpieces of the choral repertory — will be presented in settings by Baroque-era composers! There’s even a concert that features renowned countertenor Reginald Mobley and consists of music by Baroque-era composers from the New World, some of whom were from previously enslaved families of African origin. Even better, the events during the 2024-25 concert season (though perhaps not those during the June 2025 summer Festival) are being made available in a videostreamed version as well—great news for those of us who live far from New England.

Of course, something had to be left out, and this season it’s French music. So I’d like to take this opportunity to right the balance a bit with a review of two new releases of French operas by renowned and influential figures from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries: Mondonville and Destouches. (BEMF has given some spiffy renderings of French works in the past: I raved here about their recent recording of Desmarest’s Circé, a work that they performed to great acclaim during the summer festival of 2023.)

The two recordings I’m discussing here are world premieres and appear on the Chateau de Versailles Spectacles label. Versailles Spectacles has in recent years become one of the major purveyors of French (and some non-French) Baroque music. For decades now, French recordings of classical music, in general, have had a hard time becoming known in America, except ones that were made available on an international label, most notably Angel/EMI/His Master’s Voice. Specifically French labels such as Arion, Calliope, Erato, and Auvidis Valois were often not widely distributed and reviewed in the US. Some important and interesting recordings popped up on budget labels (including Musical Heritage Society, available only by mail order). Many others did not reach us at all.

Over the past decade or so, two major French labels have been changing that. One is Bru Zane, the label of the Center for French Romantic Music. I have reviewed over a dozen French-opera recordings brought to us by that estimable organization and have been delighted by the consistently high level of performance and (in the accompanying hardcover book) presentation. (Click here for operas by Gounod, Saint-Saëns, and Reynaldo Hahn; and here’s an 8-CD set of works by female composers who were born in France, including one from its Alsatian region: Marie Jaëll.)

The other label, whose praises I want to sing today, is Chateau de Versailles Spectacles (which I’ll abbreviate to simply “Versailles”). This seems to be a kind of offshoot of the French government’s use of the palace at Versailles as a concert space, or, rather, concert spaces in the plural, since some of the recordings are made in the palace’s magnificent chapel, others in its small, wood-paneled Royal Opera, and yet others in the Hall of Mirrors or in the small, private theater in Marie Antoinette’s residence. Some releases come from halls elsewhere in France but (confusingly) still bear the label-name Versailles.

Hasnaa Bennani, Moroccan-born soprano who sings gorgeously in two French Baroque opera recordings. Photo: ‘bdllah Lasri

There are now some 120 recordings available on the Versailles label, and I’ve reviewed a few of them here already, including a different but equally splendid recording of Desmarest’s Circé, the opera that I mentioned above in regard to the Boston Early Music Festival. Nearly all are of music from before 1800, and most of the works are French (or Latin, in the case of sacred music), with some Italian because Italian opera was performed in France during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (and of course even more so thereafter). The Versailles catalogue also includes Handel’s Messiah.

One of the albums that I reviewed here was of largely historical interest: the French adaptation of Pergolesi’s La serva padrona that aroused so much debate in France during the mid 1700s. Two others each came with a DVD that turned out to be even more captivating than the audio CD heard on its own (Charpentier’s David et Jonathas and Rousseau’s Le devin du village).

The latest two releases are absolute winners and show, between them, how diverse French Baroque music could be. The works of Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville (1711-72) were widely hailed during his lifetime, especially his “grand motets” but also his operas. Apparently Le carnaval du Parnasse is the last of his operas to be recorded, though I have not encountered any of the others before. What I hear, I like, indeed rather adore! Mondonville was an immensely tuneful composer, a fact that writers attribute to his having been born and raised in the south of France, with its thriving village traditions of singing and dancing, and the playing of the galoubet (small flute) and tambourin: a long “tenor”-pitched drum played with a stick and not to be confused with a tambourine (“tambour de Basque”), which of course is small and high-pitched and has numerous jingles attached to its rim, and is struck with the hand. (The tambourine is known in French as a “tambour de Basque.”)

The plot of this Mondonville work is relatively devoid of dramatic intensity, instead making space for one joyful celebration after another, including celebrations of nature (e.g., bird song, in flute and/or voice). Amazingly, despite there being so many dance-like movements, the music never becomes predictable or routine. It helps that phrase structure is often unpredictable. I was thrown, in CD 1, track 9, by the fact that the first phrase is a hemiola, before the basic triple meter has even been established. Fortunately, the passage recurs several times, enabling me to figure out where the downbeats are probably placed in the score. This doesn’t sound like a miscalculation on Mondonville’s part, rather like an instance of fascinating compositional technique, pungently purveyed by first-rate performers. One other intriguing feature is that the prologue involves a disagreement between two shepherdesses (or whatever their societal identity is) about the relative merits of Italian and French music, in the course of which each illustrates her point by a short aria in that language and style.

The performers include several that I have praised here before (Gwendoline Blondeel and Mathias Vidal, each in two roles as the opera moves along) and some that I’m delighted to have now gotten to know, most notably the Moroccan-born Hasnaa Bennani (in four roles). Bennani’s voice is jewel-like: tightly focused and capable of all kinds of quick movement, like the feet of a skilled figure skater. And she’s always perfectly on pitch. I hope that opera companies in America are noticing her!

André Cardinal Destouches (1672-1749), by contrast, was a relatively strict follower of the tradition of “tragédies lyriques” in the manner of Lully and Rameau. Indeed, he became the director of the Paris Opéra in 1713 and held the position for 17 years. His Télémaque et Calypso was an enormous success at the time, being brought back in several successive seasons. We hear here his own reworked version of it from 1730 (though the booklet gives only scant information about how it differs from the original).

Destouches’s opera is freely based on a famous novel, Fénélon’s Les aventures de Télémaque. The reference is to Telemachus, the son of the famous Ulysses, hero of The Odyssey. (The name has nothing to do with Telemark, a region in Norway.)

Destouches’s opera is freely based on a famous novel, Fénélon’s Les aventures de Télémaque. The reference is to Telemachus, the son of the famous Ulysses, hero of The Odyssey. (The name has nothing to do with Telemark, a region in Norway.)

This novel was much discussed at the time for its relatively liberal pronouncements: notably its opposition to the principle that a ruler could and indeed should exert absolute power over his subjects. (For its echoes in literary and theatrical debates, with further implications for some operas by Mozart, I recommend the fascinating recent study by musicologist Katharina Claudius, Opera and the Politics of Tragedy: A Mozartean Museum.) These political opinions of course were not included in the opera’s libretto, which, instead, weaves a partly new story out of certain of the book’s characters and plot elements. Prominent elements include threats of individuals being sacrificed to placate the god Neptune, and a chain of frustrated loves as in the classic French dramas of Racine: Calypso, wounded at Ulysses’s having left her (or, as she puts it, having been taken away from her by Neptune), has set her sights on Ulysses’s son Telemachus, who is instead drawn to Calypso’s prisoner Eucharis (actually named Antiope, and daughter of Idomeneus); also the foreign prince Adrastus yearns hopelessly for Calypso and knows and eventually reveals Eucharis’s true identity and thereafter dies (having been wounded in battle by Telemachus).

The music is, appropriately, more serious than in the Mondonville, with arias being set up by richly expressive interchanges between characters, and these interchanges are supported by a fully written out orchestral score, not by a semi-improvised basso continuo group as in Italian operas of the period.

Destouches and his librettist find ways to insert at various points danced, or danced and sung, “divertissements,” such as dances for the demons of Hell that Calypso invokes in Act 1, and a full entertainment, extending across ten tracks, that Calypso summons up in Act 3 to try to win Telemachus’s affections. The work ends with an orchestral storm, signaling Calypso’s being punished by a Neptune-sent seastorm. Or, as Benoît Dratwicki puts it in the booklet, this musical tempest represents the vain fury of Calypso herself at being unable to hold Telemachus’s affections.

Adrien Fournaison, a bass-baritone from France, brings a smooth and rich tone to Destouches’s Calypso et Télémaque.

The vocalists in the Destouches are just as delightful an assemblage as in the Mondonville. The only ones that they have in common are baritone David Witczak, whose singing (as in previous recordings that I’ve reviewed here) is a bit rough but very text-aware; the firm and resonant bass-baritone Adrien Fournaison; and the enchanting Bennani. I have nothing but praise for some others in the Destouches who—like Bennani and Fournaison—are new to me, including tenor Antonin Rondepierre and sopranos Isabelle Druet and Emmanuelle de Negri. Tenor Colin Isoir, by contrast, doesn’t sound ready yet for his imposing assignment as a high priest of Neptune.

The orchestras on both recordings are colorful, precise, and beautifully tuned. Instruments are used in great variety, no doubt going beyond the basics indicated in the surviving scores, yet the results always sound stylistically appropriate (at least to this non-specialist ear) and often support the mood or dramatic situation at the given moment. The glittering sounds are well captured by the sound engineers, and voices and instruments are nicely balanced.

Booklet essays in both releases are informative but often too brief. (Partly because everything has to be given in three languages, the third being German.) The English translations of the essays and librettos are sometimes stiff and overly literal, other times frankly erroneous. The aforementioned “tambourin” should of course not be translated “tambourine.” The translator would have noticed this if he had looked up “galoubet” or “tambourin” in, say, Wikipedia. (Galoubet and tambourin are traditionally played by the same musician, simultaneously. Indeed, a single musician is listed as playing both instruments in this recording.)

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is part of the editorial team behind the wide-ranging open-access periodical Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal. The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here by kind permission.