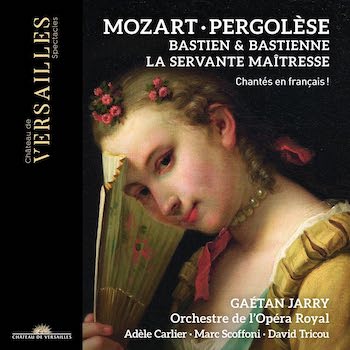

Opera Album Review: Two Comic Operas Thrive in Frenchified Versions

By Ralph P. Locke

Much-loved short works by Pergolesi and Mozart storm the stage, thanks to spiffy French dialogue between the musical numbers.

PERGOLESI: La serva padrona (in French) and

MOZART: Bastien und Bastienne (in French)

Adèle Carlier, soprano; Marc Scoffoni, tenor; David Tricou, baritone.

Opéra Royal Orchestra, cond. Gaëtan Jarry.

Versailles Spectacles [2 CDs] 42 + 47 minutes

Opera is, perhaps because of its visual and theatrical elements, one branch of “classical music” that seems to be thriving and drawing new audiences, whereas symphonic concerts and chamber and solo recitals seem to be having more trouble attracting younger listeners, especially.

Opera is, perhaps because of its visual and theatrical elements, one branch of “classical music” that seems to be thriving and drawing new audiences, whereas symphonic concerts and chamber and solo recitals seem to be having more trouble attracting younger listeners, especially.

But even opera needs retooling to feel relevant to many people. Hence the emphasis, so often, on imaginative and/or updated sets, costumes, and onstage movement — even when these contradict the explicit instructions in the libretto and stage direction and the implications in the composer’s score.

One other way that opera can become more communicative today is to perform it in the vernacular. This was the practice in the US in some opera houses and student productions until the advent of supertitles. It has the advantage that the cast members can inflect the text in specific ways, perhaps somewhat differently from one performance to the next, and all of this reaches the audience directly — indeed, the audience is watching the singers because they’re not having to glance up repeatedly at the supertitles.

Alas, opera sung and spoken in translation is hard to find nowadays. So I was particularly pleased to receive a two-CD set of two standard short operas, sung and spoken in French. The release provides a nice reminder of the fun and flair that opera can bring when done in the vernacular.

Both operas are from the mid-18th century, and we encounter them here in versions pointedly adapted for French singers and listeners — and audience members — today. The performances are delightful, though (as I’ll indicate) not challenging the best previous recordings done in the original languages. They certainly made me wish we had equivalent recorded versions in English!

La serva padrona (1733) is the single best-known comic opera from the first half of the 18th century, unless one counts, say, the “Coffee Cantata” of Bach as a kind of opera. (Also, Handel’s Italian opera Serse, about the love affairs of the Persian ruler Xerxes, is comical in many moments.) The plot involves a wealthy man, Uberto, and the strong-minded servant, Serpina, whom, as he gradually begins to realize, he loves.

Conductor Gaëtan Jarry. Photo: Facebook

Serva has had some marvelous and effective recordings, including ones by native Italian singers who sometimes are strongest in the recitatives but acidic (the sopranos) or ungainly (the men) in the arias and duets. I know of at least seven recordings, including one from 1956 conducted (blandly) by a youngish Carlo Maria Giulini and delivered with great spirit but not ultimate polish by two of the day’s prominent opera singers, Rosanna Carteri and Nicola Rossi-Lemeni. There’s a video that also includes the serious opera with which it was originally paired in performance. Not to mention several recordings of Giovanni Paisiello’s effective setting of the same libretto (1781, first performed at the imperial residence outside of Saint Petersburg).

My favorite recording of Pergolesi’s setting, formerly a 1963 RCA Victor LP (made in stereo but the US release was mono-only), features a young Anna Moffo as Serpina and Paolo Montarsolo as the baffled Uberto; both are in superb voice and present very detailed characterizations. Alas, it seems not to be currently available for purchase, but it can be watched on YouTube, excellently acted in costume by Moffo and Montarsolo (lip-synching to their recording), with a supporting cast of equally amusing silent actors who take well-individualized roles as servants in Uberto’s house.

On this new recording the three singers have smallish but precise (not woolly) voices. Assisted by a tiny but colorful and nuanced period-instrument orchestra, they put the work across very well for Francophone listeners. The alert conductor, Gérard Jarry, sets nearly perfect tempos throughout.

Many of the recitatives are turned into spoken dialogue, which (since my French is better than my Italian) helped me enjoy these scenes between the musical numbers more immediately than when I hear the Italian original and have to look at the words. But of course one loses Pergolesi’s specific modulations and other musical devices supporting the feisty debates, play-acting, etc., between the two characters.

The version heard here has specific historical interest, in that it was created in 1754 for performances by the Favart troupe and helped stir up a lively debate about whether Italian or French was better for singing and whether operas should focus on lively tunes (of the Pergolesi type) or the more dignified and grandly declaimed melodic lines typical of the Lully-Rameau tradition. The booklet-essay explains all this in detail and informs us that the 1754 version inserts a few additional short arias and an accompanied recitative “to vary the spoken sections.” The adapter was Pierre Baurans, and his version continued to be published, and revived on Paris stages, into the early 20th century.

Bizarrely, the opera, in Baurans’s published version, loses its perfectly effective overture. Do scholars really know that no overture was performed? (There was plenty of room left on the CD to include it!) In any case, I don’t see that historical authenticity should take precedence over musical interest to quite that degree. In any case, I suspect that (outside of the Francophone world) the historically minded will be the primary audience for this version of the Pergolesi, since they can hear what astounded French audiences in 1754 and got debated in newspapers and pamphlets.

Bastien und Bastienne was written by the 12-year-old Mozart in 1768. In this work, the soprano is in love with the tenor, and the baritone is a wise older man who advises her to act coldly to her guy to get him to pay more attention to her. It, too, has had a lively existence on the stage and on recordings. Most of the arias and duets are quite short (e.g., two minutes long), though they become longer and more elaborate as the work reaches its climax and conclusion. (This will be true of The Magic Flute as well, 23 years later: in that work the spoken dialogue nearly disappears in its final scenes, and “music drama” takes over.) Perhaps the most amusing number is a “conjuration” aria for the wise man, full of nonsense syllables and stormy scurryings in the strings. The old man’s hocus-pocusing, pointedly, achieves nothing, and the plot must then move in a new direction.

I know of at least a half-dozen recordings, including a highly capable one featuring Peter Schreier and Theo Adam (with the less-distinguished Adele Stolte) and one conducted by John Pritchard (with Walter Berry as the helpful/annoying older guy). I streamed a recording by soloists from the Vienna Boys’ Choir (yup, a young male sings the role of Bastienne, without any exaggerated “girlishness”), which has a lot of charm, not least in the dialogue (spoken with Austrian accents). I also enjoyed the musical numbers in a recording with such international soloists as Slovakian-born Edita Gruberová, conducted by Raymond Leppard, but the German dialogues were delivered stiffly.

Scene from the staging of Pergolesi’s La serva padrona (in French) at the Théâtre de la Reine (Versailles). Photo: Agathe Poupeney

The opera’s plot was lifted from Rousseau’s Le devin du village (1752), a work that itself has had a raft of recordings, including a delightful one featuring the young Nicolai Gedda. (There is a 2017 CD + DVD, boxed together, from a carefully historical production at this same small theater in the Versailles palace, known as the Queen’s Theater, to distinguish it from the Versailles Royal Opera House.)

The Mozart work is treated more respectfully here than is Pergolesi’s: no music is cut (since the original had spoken dialogue, not recitatives), nor is any added. The musical numbers use French words that were written by two noted professionals (the writer Henry Gauthier-Villars, known as Willy, who was the first husband of the novelist Colette; and the librettist and music publisher Georges Hartmann) and were used in a 1900 production at the Opéra-Comique. The spoken dialogue was concocted for present purposes by the young actor-director Laurent Delvert. It is very effective, and rendered with much vivaciousness and character by the three singers. They handle the arias well enough, though without the variety and impact of singers like Gruberová and Schreier. I enjoyed hearing Mozart sung in French (my first time ever), and suspect that others, too, will delight in hearing these familiar works come alive in a new way. You may not want to purchase it, but it is very much worth listening to if you have access to it through streaming. (The whole nature of gaining access to classical music has changed now that we have Spotify and other such services.) You can see a few snippets of the stage production here.

The two essays in the booklet are less than helpful; one is confusingly organized, and the other (by the stage director) is a standard overview of Mozart’s whole career, offering little insight into Bastien. Worse, the English translations throughout the booklet, credited to a firm rather than an individual, are often misleading. I hope that the organizers of the Versailles CD series will hire more appropriate writers and translators in the future. (The spoken and sung texts are given also in the French that we hear and in German — but not in Italian, even for the Pergolesi.)

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is part of the editorial team of Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal, an open-access source that includes contributions by performers (soprano Elly Ameling) as well as noted scholars (Robert M. Marshall) and is read around the world. The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.