Opera Album Review: A Fabulous World Premiere Recording of a Major Work of the French Baroque Era

By Ralph P Locke

This splendid album offers ample proof that Henry Desmarest stands shoulder to shoulder with his major 17th-century French contemporaries, Lully and Marin Marais.

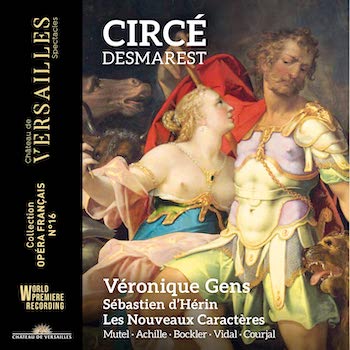

DESMAREST: Circé

DESMAREST: Circé

Véronique Gens (Circé), Mathias Vidal (Ulysse), Caroline Mutel (Astérie, Minerve), Cécile Achillle (Éolie), Romain Bockler (Polite, Phantase), Nicolas Courjal (Elphénor).

Les Nouveaux Caractères, cond. Sébastien d’Hérin.

Chateau de Versailles Spectacles 085 [2 CDs] 155 minutes

Click to purchase or to stream it (with a subscription).

Henry Desmarest (1661-1741) was one of the most prominent composers and conductors (music directors) during the French Baroque era, active in both opera and sacred music. His life could make a movie: in 1698 he kidnapped the woman he loved and, together, they fled to Brussels, lest he be put to death. He later held prominent positions leading the musical forces of the king of Spain (Philip V) and, thereafter, the duke of Lorraine. He was finally allowed back in Paris in 1720. (The name is sometimes spelled Desmarets and, in his lifetime, as Desmarais, which risked confusion with the renowned composer and gamba player Marin Marais.)

Circé may be his greatest work. It certainly is the one that modern-day listeners now have a chance to get to know most intimately, because two recordings are coming out almost simultaneously. The Boston Early Music Festival has recently released its recording (featuring the marvelous Lucile Richardot), which I shall review in a separate article. A live performance, with many of the same singers, was received with raptures in June. (See Lee Eiseman’s detailed review in the Boston Musical Intelligencer.)

Meanwhile, Chateau de Versailles Spectacles has released its own recording (made in January 2022), though, like some other recordings from that label, I don’t find it on Spotify. That recording, reviewed here, features a singer in the title role, Véronique Gens, who is even more renowned than Richardot. Indeed, on the box, Gens is the only singer whose full name is given, and in larger type. I would object if she weren’t so marvelous in this role. As she pretty much always is, no matter what the repertory: I have previously praised her in wildly different works by Rameau, Félicien David, and Offenbach.

Conductor Sébastien d’Hérin and Les Nouveaux Caractères in action. Photo: Pascal Le Mée

People who love Baroque music often focus on Italian and Italianate music (Vivaldi and Handel) but stay away from French works, perhaps because so much of the latter is operatic. But they needn’t fear: unlike Italian operas of the period, French operas tend to have no recitatives accompanied by a harpsichord or continuo group. Instead, the connecting passages are often much more melodic and shapely, and accompanied by the full orchestra. Plus there are far more choral passages and dances than in a typical Italian opera of the period. The net result is that one can put an act of Lully or Rameau into one’s CD player (or whatever!) and be relatively assured of 25 to 40 minutes of continuous and varied delight. True, one gains more by following the libretto and thereby becoming aware of the expostulations of the various characters. But my point is that French Baroque opera is more continuously music-driven than Italian opera of the same period, less bifurcated into virtuosic arias on the one hand and word-dominated recitation on the other.

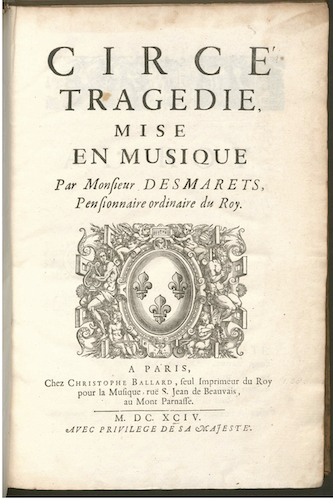

Desmarest’s Circé (1694) is freely based on Greek legends about Ulysses (Odysseus) and how he and his crew were entrapped for a time by the sorceress Circe. The libretto is, somewhat unusually for the time, by a woman: Louise-Geneviève Gillot de Saintonge (1650-1718). After a prologue in praise of the king of France and offering the opera as a pleasant and needed distraction (from the Nine Years’ War, 1688-97), we are treated to a series of marvelous events, each often culminating in some kind of theatrical display.

Circe, eager to keep Ulysses, whom she loves, on the island, has turned most of his companions into statues so the ship cannot leave. (I’ll use the normal English names for the characters.) Circe frees the crew to prove her love and demonstrate her power, but Ulysses’s loyal friend Elpenor does not want to leave because he has fallen in love with Asteria. Ulysses has a dream scene, in a forest whose trees are the former lovers of Circe, and Elpenor reveals Ulysses’s plan of fleeing in the ship. Elpenor pledges his love to Asteria but is rejected and commits suicide. At Elpenor’s tomb, Circe tries to learn from his ghost the name of the woman that Ulysses loves. (This scene relates to the Italian tradition of scenes in which a sorceress invokes the shades of Hell, as Medea does in Cavalli’s Giasone, one of the most widely performed operas of the 17th century.) The Eumenides pursue Ulysses, and Mercury appears, giving a magic flower to Circe. Aeolia (does she represent the famous floating island from Greek mythology?) enables Ulysses and his crew to leave. Circe tries to use the magic flower to frustrate their escape, but in vain. Despairing, she destroys her island, which sinks beneath the waves.

Circe, eager to keep Ulysses, whom she loves, on the island, has turned most of his companions into statues so the ship cannot leave. (I’ll use the normal English names for the characters.) Circe frees the crew to prove her love and demonstrate her power, but Ulysses’s loyal friend Elpenor does not want to leave because he has fallen in love with Asteria. Ulysses has a dream scene, in a forest whose trees are the former lovers of Circe, and Elpenor reveals Ulysses’s plan of fleeing in the ship. Elpenor pledges his love to Asteria but is rejected and commits suicide. At Elpenor’s tomb, Circe tries to learn from his ghost the name of the woman that Ulysses loves. (This scene relates to the Italian tradition of scenes in which a sorceress invokes the shades of Hell, as Medea does in Cavalli’s Giasone, one of the most widely performed operas of the 17th century.) The Eumenides pursue Ulysses, and Mercury appears, giving a magic flower to Circe. Aeolia (does she represent the famous floating island from Greek mythology?) enables Ulysses and his crew to leave. Circe tries to use the magic flower to frustrate their escape, but in vain. Despairing, she destroys her island, which sinks beneath the waves.

The singers here are all French and sing the words clearly and naturally. (Two sing more than one role.) Caroline Mutel’s bright soprano contrasts nicely with the darker shades of Véronique Gens, and Mathias Vidal sounds as bright, clear, and heroic as he seemingly always does. Nicolas Courjal manages the baritone role of Elpenor quite well; I prefer his singing here to what I have heard him do in 19th-century works, for which he didn’t seem to have enough vocal heft and resorted to emphatic huffing.

The orchestra known as Les Nouveaux Caractères is under the alert direction of Sébastien d’Hérin. The six-person continuo group includes two theorbos (long-necked lutes) and there are 26 orchestral players and close to two dozen in the chorus (divided in the usual French fashion: STTB). The result is a rich tapestry of sounds that will waft you away (on a floating island?), even if you’re not thinking much about the astonishing events that are supposed to be happening on the stage. A three-minute video gives a good sense of the varied delicacies on display.

The recording was made during a concert performance (plus touch-up sessions) in the renowned and intimate Versailles Opera House in January 2022. It has made me realize anew what wonders the French Baroque created. Desmarest is a name I shall now look for eagerly.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Chateau de Versailles Spectacles, Circe, Henry Desmarest, Les Nouveaux Caractères, Mathias Vidal, Sébastien d’Hérin