Opera Album Review: A Groundbreaking French Grand Opera Receives Its First Major Commercial Recording

By Ralph P. Locke

Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable paved the way for major works by Meyerbeer himself, Halévy, Verdi, Wagner (in German), Saint-Saëns, Massenet, and others — and this splendid performance shows why.

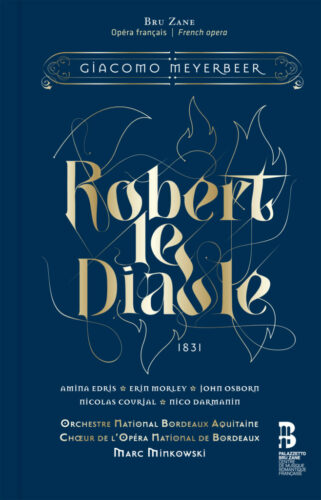

Meyerbeer: Robert le diable

Erin Morley (Isabelle), Amina Edris (Alice), John Osborn (Robert), Nico Darmanin (Raimbaut), Nicolas Courjal (Bertram).

Bordeaux Aquitaine National Orchestra and Bordeaux Opera Chorus/ Marc Minkowski.

Bru Zane BZ 1049 [3 CDs] 237 minutes

Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) was one of the most often-performed opera composers of the nineteenth century, and one of the most influential. His four grand operas were widely praised and loved, and were taken as models by composers as varied as Halévy, Berlioz, Verdi, Gounod, Wagner (his early Rienzi), Bizet, Saint-Saëns, and Massenet. Three of the four — Les Huguenots, Le Prophète, and L’Africaine — became well known some decades ago through recordings and videos featuring major singers, including Joan Sutherland, Martina Arroyo, Marilyn Horne, and Plácido Domingo. The first of the four, Robert le diable (1831), has remained somewhat in the shadows. All the more reason to hail this largely splendid studio (and/or in-concert) recording, made during a week in September 2021.

Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) was one of the most often-performed opera composers of the nineteenth century, and one of the most influential. His four grand operas were widely praised and loved, and were taken as models by composers as varied as Halévy, Berlioz, Verdi, Gounod, Wagner (his early Rienzi), Bizet, Saint-Saëns, and Massenet. Three of the four — Les Huguenots, Le Prophète, and L’Africaine — became well known some decades ago through recordings and videos featuring major singers, including Joan Sutherland, Martina Arroyo, Marilyn Horne, and Plácido Domingo. The first of the four, Robert le diable (1831), has remained somewhat in the shadows. All the more reason to hail this largely splendid studio (and/or in-concert) recording, made during a week in September 2021.

Meyerbeer (born Jakob Liebmann Beer), a Jewish composer from the Berlin area, was forty when Robert was mounted via an expensive and artistically exquisite production at the Paris Opéra. He was already experienced, having spent some years in Italy composing highly accomplished and commercially successful works, notably Il crociato nell’Egitto. (Readers of The Arts Fuse may recall how taken I was with two of Meyerbeer’s pre-Paris operas: Romilda e Costanza and his very first, in German: Alimelek, as well as with his musically rich 1854 French comic opera L’Étoile du nord.)

When Meyerbeer moved to Paris, he held back from offering an opera until he had observed closely the features of such important grand-scaled French works as Auber’s La Muette de Portici and Rossini’s Guillaume Tell (respectively, 1828 and 1829).

Robert le diable was first intended for the Opéra-Comique: it therefore has the typical pairing of a serious (upper-class) couple and a naive or comical (lower-class) one, and was originally drafted with spoken dialogue between the numbers. But the theater was beginning to go through some turmoil, and Meyerbeer ended up offering Robert to the Opéra instead, where works were required to be sung all the way through and were expected to emphasize noble ideals more than homespun comedy. One result is that the easily duped Raimbaut disappears halfway through (though he still gets a superb ballad in Act 1).

Edgar Degas, The Ballet from Robert le Diable, 1871.

Audience members have never been greatly disturbed by this one inconsistency because there is so much that is wonderful and cogent in the work. Listening to it in this recording, my ear was seized time and time again by the appealing and not-always-predictable melodies (a particularly grand one in the Act 5 trio), by apt harmonic touches, and by colorful contrasts in the orchestration (horns, reminiscent of Weber’s Der Freischütz, before Raimbaut’s ballad; “rustic” high winds before peasant-lass Alice’s aria in Act 3; and a muted solo trumpet, almost like a voice from Heaven, when Robert reads his mother’s final words in Act 5).

Most of all, the main figures — the Princess Isabelle of Sicily, Duke Robert (from far-off Normandy), Alice (Robert’s adopted sister), and Bertrand (Robert’s friend, who turns out to be his father and also his nemesis) — are each characterized adroitly, through some of the most memorable music that I have encountered in several years of reviewing here. And one effect is astounding: the moment in Act 4 where Robert waves a magic branch and everybody else on stage becomes quasi-frozen in place, allowing Robert to sing of Isabelle’s beauty. His voice gradually reawakens the princess and lulls her in a stirring duet. The whole passage feels like something out of an imaginative silent film, though of course the influence really goes the other way: early film grew from the rich soil of theatrical conventions as manifest in this very opera (which was still in the international repertory at the beginning of the twentieth century).

I knew some of the passages well already. Bertram, who is in league with the devil (much like Kaspar in, again, Der Freischütz), has two scenes in which he invokes the spirits of Hell, and these have been performed and recorded separately by José van Dam, Samuel Ramey, and others. The best-known moment from the work is Princess Isabelle’s plea to Robert to cease his dealings with the evil Bertram: “Robert, Robert, toi que j’aime.”

But there is so much more! Scene after scene unrolls naturally and persuasively, thanks to the gifts of a generally superb cast and the Bordeaux orchestra and chorus, powerfully and adeptly led by Marc Minkowski. “Robert, Robert” is taken more slowly than I inherently like, but soprano Erin Morley is in superb control, and Robert’s repeated responses of “Non, non, non, non” sound less perfunctory at this tempo. (Still, Beverly Sills’s famous recording of the aria, superbly conducted by Charles Mackerras, feels somehow even more heartfelt.)

Soprano Erin Morley as Isabelle. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The vocal pleasures are many. Morley (from Salt Lake City) must be one of the best lyric-coloratura sopranos around, and I’m glad to encounter her on a recording in a major role. Amina Edris (from Egypt, but raised in New Zealand) is Morley’s match in a role that has its own share of florid passages and touching ones. John Osborn (born in Sioux City) is a better-known quantity, thanks to such things as the Met telecast of Rossini’s La donna del lago (with DiDonato and Flórez) and a fine recital of arias associated with the French tenor Gilbert Duprez. Duprez famously became a chief exponent of this opera’s role of Robert once Adolphe Nourrit’s voice began to decline. Osborn doesn’t disappoint here, singing grandly whenever required and, at other times, filing his voice down to a daringly vulnerable half-voice. Nico Darmanin (from Malta) is marvelous as the easily fooled Raimbaut, and his French sounds totally convincing.

The one annoyance comes from Nicholas Courjal. As on other recordings that I have reviewed (e.g., Félicien David’s Herculanum), his voice lacks richness and has a persistent wobble that, among other things, can make it hard for the listener to identify the pitch in quick passages. A native French-speaker, he conveys well the sneakiness and cravenness of this inherently repulsive figure. But he doesn’t sound slick enough in his Act 3 exchange with Alice, and I definitely wouldn’t want to hear him in certain standard baritone roles that require steadiness of tone (e.g., Verdi’s Count di Luna or Germont père).

There have been previous recordings, mostly on minor or “pirate” labels. Wikipedia lists no fewer than seven, featuring renowned singers of the respective era, e.g., Renata Scotto, June Anderson, Patrizia Ciofi, Alain Vanzo, Rockwell Blake, Bryan Hymel, Boris Christoff, and the aforementioned (and unsurpassable) Samuel Ramey. Two of these are videos. Indeed, Robert, more than certain other operas, would definitely gain from being seen. I haven’t even mentioned the Act 3 ballet of the nuns, who rise from their graves and throw off their cloaks to tempt Robert. (This ballet is famous from a Degas painting.) But Robert can be, I found, coherent purely as a listening experience; and the introductory essays in the accompanying book will tell you most of what you need to know to enter into the world of this amazing and influential work. For more detail, see Steven Huebner’s entry on Robert in OxfordMusicOnline.com. This two-minute trailer gives a sense of the treasures on offer:

Robert le diable is long and has often been trimmed somewhat, as indeed is done here. (We lose the beginning of the scene in which Robert, at Bertrand’s urging, gambles all his money and armor away.) Admirably, the printed libretto gives — against a shaded background — the words for passages that are not heard.

One small complaint: the track list is not adequately detailed. Isabelle’s sad-yet-coloratura-studded aria “En vain j’espère” is not listed, nor is the cabaletta of rejoicing that follows it; the only title given for that track is the recitative that opens the whole solo scene. Listeners need more help than this when navigating a long, unfamiliar, yet wondrous opera!

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Bordeaux Aquitaine National Orchestra, Bordeaux Opera Chorus, Bru Zane, Erin Morley, Meyerbeer, Ralph P. Locke