Opera Album Review: Zoroastre and His Sun Worshipers Vanquish Louts in a World-Premiere Recording of Rameau’s 1749 Opera

By Ralph P.Locke

Some of France’s best early-music singers and a splendid period-instrument band make this Zoroastre a perfect introduction to the pleasures of Baroque music.

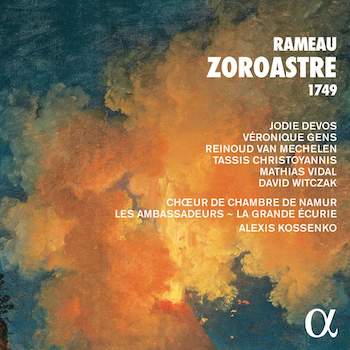

Zoroastre: Jean-Philippe Rameau

Jodie Devos (Amélite), Véronique Gens (Érinice), Reinoud van Mechelen (Zoroastre), Tassis Christoyannis (Abramane), Mathias Vidal (three roles), Gwendoline Blondeel (two roles), David Witczak (four roles).

Namur Chamber Chorus, Les Ambassadeurs, La Grande Écurie, cond. Alexis Kossenko.

Alpha 891 [3 CDs] 166 minutes

You probably are familiar with some other works relating to the Persian philosopher Zoroaster. A version of him appears, sometimes with the name rendered a bit differently, in Handel’s Orlando, in Mozart’s Magic Flute (with his name shortened to Sarastro), or in the title of Richard Strauss’s Nietzsche-based Also sprach Zarasthustra.

You probably are familiar with some other works relating to the Persian philosopher Zoroaster. A version of him appears, sometimes with the name rendered a bit differently, in Handel’s Orlando, in Mozart’s Magic Flute (with his name shortened to Sarastro), or in the title of Richard Strauss’s Nietzsche-based Also sprach Zarasthustra.

Here he’s the central figure, and a tenor, presented as the leader of a cult that worships the sun. This much is historically accurate. (Except that nobody knows how high his voice was!)

Zoroastre leads his followers to fight against the tyrant Abramane (baritone), who has usurped the throne of Bactria, has exiled Zoroastre, surrounds himself with priests, and carries a magic wand. Other characters include Érinice, who loves Zoroastre but sides with Abramane because Zoroastre spurned her love, and Amélite, who is inconsolable ever since Zoroastre was sent into exile, and whom, at the command of Érinice, evil spirits abduct. There is eventually a great battle between the forces of light and the forces of darkness, but, protected by the Spirits of the Elements (and, we are also told, by Heaven), the good guys and gals win.

This being a “tragédie lyrique,” the arias are mostly short, and there are numerous choruses and dances, including when Amélite’s female companions console her and when Zoroastre celebrates the marriage of several couples, plus a “figurative ballet” for the Cruel Spirits, led by Hate, Jealousy, Despair, and Vengeance after the evil Abramane has sacrificially murdered (by ax and then immolation) some hapless victims.

In short, this is an opera that, for home listening, has a large amount of orchestral music, and only the briefest of stage directions to tell us what is going on during those passages. I loved it, and even had fun imagining what the dancing and miming might be like.

The orchestration is remarkably rich, in part because the performers have staffed the orchestra quite fully, following evidence of what was done at the time: we hear four each of flutes, oboes, and bassoons, and no fewer than eight cellos. Conductor Alexis Kossenko has, based on some surviving reports, replaced oboes with clarinets in certain numbers involving evil characters, to darken the sound. The continuo group is silent in movements that are purely orchestral, thereby increasing the variety of sonic images as the opera moves along.

Soprano Véronique Gens. Photo: Alpha Classics

The final confrontation between Abramane and Zoroastre, with their respective supporters, is carried out powerfully by Rameau (and his librettist Cahusac). First Amélite interposes herself between the two camps; then “the People” join her, swords in hand. Next, Zoroastre and Abramane start singing at each other simultaneously (to different threatening words), while the orchestra swirls away in a minor-mode “storm” music, and we hear some simple but effective thunderclaps from the percussionist (a woman, by the way: Marie-Ange Petit). The two choruses now join in to build the whole struggle to a satisfying climax–at which point the ground opens under the feet of Abramane and his evil priests. After all this, Amélite accepts Zoroastre’s offer of marriage, and the opera ends with a celebratory series of songs and dances to honor the virtuous couple and the triumph of Heaven over Hell.

Throughout the recording, apparently made during concert performances (plus “patch” sessions?), the seven solo singers demonstrate that they are among the most accomplished on the French scene today. I have praised three of them over and over again here: Véronique Gens, Mathias Vidal, and Tassis Christoyannis. (The latter is Greek-born. Over the years his French has become near-native.) Jodie Devos is a major young high soprano, pure and infinitely flexible. Her sound is considerably brighter than that of Gens, which helps the listener tell them apart. Belgian-born Reinoud van Mechelen is a new name to me, but, in the title role, he quickly claims our attention as one of the best Baroque-music tenors around. (I see that he has also sung later roles, such as Mozart’s Belmonte, Bizet’s Nadir, and Delibes’s Gérald.)

All the singers use standard French operatic pronunciation, with a quasi-Italian trilled r rather than the more vernacular guttural r that can sound a bit like a German ch. The chorus and early-instrument orchestra are beautifully in tune with each other, and conductor Kossenko keeps everything moving forward in (as needed) a graceful, touching, or forceful manner.

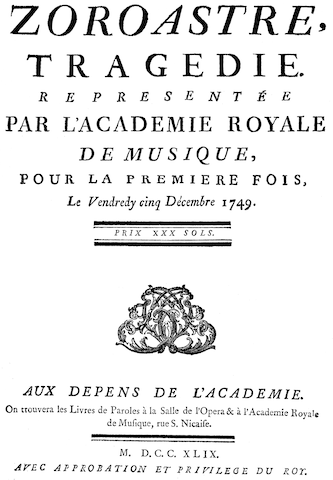

There have been other recordings of this work, but they used the 1756 reworking. This is a world-premiere recording of the original 1749 version (using the critical edition prepared by Graham Sadler). It thus recommends itself automatically to people wanting to gain a full sense of the achievements of Rameau. They won’t be disappointed, and listeners who are newer to “tragédie lyrique” and (a related genre) “opéra-ballet” may actually find this recording a good place to start, along with some recording or video of Rameau’s Les Indes galantes. See my review of the latest recording of Les Indes galantes, with remarks about earlier recordings.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is on the editorial board of a recently founded and intentionally wide-ranging open-access periodical: Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal. The present review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Alexis Kossenko., Alpha-Classics, Jean-Philippe Rameau, La Grande Ecurie, Les Ambassadeurs, Namur Chamber Chorus