Book Review: A Complicated Story — Noh Theater and Modernism

Carrie J. Preston refuses to characterize these cultural exchanges in moralistic or narrowly political terms (via such words as “theft” and “appropriation”).

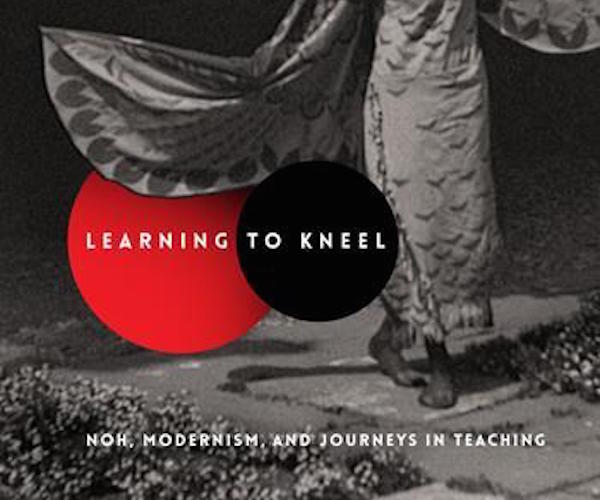

Learning To Kneel: Noh, Modernism, and Journeys in Teaching by Carrie J. Preston. Columbia University Press, 352 pages, $35.

By Ian Thal

Since the nineteenth century, commerce between Japan and the West has been lively and extensive, whether in terms of cultural objects (Salem’s Peabody-Essex Museum hosts an impressive collection), pop culture, or the fine arts. Of course, this kind of exchange can become tricky in an age of identity politics and sloganeering. A project with the backing of cultural institutions in both the United States and Japan can turn into an act, at least to some, of “cultural appropriation.”

For example, protests and counter protests erupted at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston last year around its “Kimono Wednesdays” programming. Claude Monet’s La Japonaise (1876) had just returned from a tour of Japan. A kimono based on the one worn by Madame Monet in the painting was given to the MFA; museum visitors were invited to wear copies. Protesters — much to the surprised bewilderment of the Japanese Consulate and some Japanese-American cultural institutions — linked the invitation to Western imperialism as well as to the sexual fetishization of Asian women in the Western male imagination. The MFA responded by canceling Kimono Wednesdays.

Nowadays, cultural exchanges are rarely free of charges of exploitation and misunderstanding. In Learning To Kneel: Noh, Modernism, and Journeys in Teaching, Carrie J. Preston provides a nuanced understanding of these complicated interactions, exploring the influence Noh theater had on those who helped define Modernism in Europe and America as well as how Modernism reshaped Noh in Japan – and globally.

Preston did not just research documents, but she submitted (a key term here) to Noh training, both in order to understand the pedagogy of the theatrical form’s tradition but also to question assumptions of regarding egalitarianism in the American university. The practice of submission in Noh, in which students learn repertoire, texts, movements, and vocalizations through a ritualized imitation of the teacher — often while in an uncomfortable kneeling position — presents a radical contrast with the supposedly egalitarian pedagogy of the American classroom. However, Noh training is productive because it forms an intimate relationship between student and teacher, creating a level of mastery that helps any group of Noh practitioners to stage a well-known piece of repertoire with minimal rehearsal time.

Ezra Pound was one of the first and most prominent modernist poets to draw upon Noh, working from Ernest Fenollosa’s scholarly translations to create his poetic adaptations of Noh plays. The latter helped shape the reception of Noh in the English speaking world. While scholars and critics have questioned the accuracy of the Pound-Fenollosa translations (as if any translation of a poetic or performance text could be wholly accurate), Preston focuses on why Pound was attracted to Noh; the answer has as much to do with his desire to forge a new Modernist aesthetic as it does with his fascist politics. Like many of today’s demanding aesthetes, he feared that commerce — compounded by the democratization of taste promoted by the market place — promoted mediocrity in the arts. Pound attributed the sublimity he saw in Noh to its having found favor among the aristocracy of feudal Japan. And it should not be surprising that he saw the modern equivalent of this warrior culture generated by fascism.

In 1914, while he was serving as William Butler Yeats’ live-in secretary, Pound published his translation of Hagoromo. (The play would figure later in Pound’s understanding of imagism, as well as in his Cantos.) Yeats’ own interest in Noh was also, in part, political. As an Irish nationalist, his collaborations with the Abbey Theatre centered on forging a distinctly Irish dramaturgy removed from the naturalism and melodrama that dominated English stages. Drawing on Noh’s use of masks, movement, music (and on Hagoromo), Yeats wrote At the Hawk’s Well (1916), part of a cycle of plays inspired by the mythological Irish hero Cuchulain. Preston notes that Yeats’ anti-colonialist project was often funded by the English upper-class and that his politics flirted with both republicanism and fascism.

A key collaborator with both Pound and Yeats was the Japanese performer Itō Michio. Itō, though not a Noh actor, had been trained in the Japanese classical dance, nihon buyō, which shares some formal elements with Noh. Itō would prove to be instrumental, not just in Yeats’ own staging of At The Hawk’s Well, but bringing in the play to both America and Japan, where it has since been integrated into the modern repertoire. At the same time, Itō Michio pursued a varied career on three continents as a modern dance soloist as well as a stage and film actor known for “exotic” roles. He also brought American=style popular stage spectacle to Japan, which makes his legacy a difficult one for today’s scholars to fully comprehend.

Preston undercuts the popular notion Noh has largely remained unchanged since the 19th century. Japanese artists were profoundly interested in modernity. The Euro-American appetite for Japanese literature may have been largely limited to classic texts, but Japanese readers enjoyed both classic and modern works in translation. Japanese artists were also interested in new technologies and media. (Preston perceptively analyzes filmmaker Ozu Yasujirō’s use of Noh in A Story of Floating Weeds.) At the same time the Imperial Japanese government encouraged presentations of the traditional arts (both classical and popular) as an affirmation of national identity, the artists were exploring conception of the self through the creation of new work that drew on communist, fascist, and modernist themes. Of course, starting in 1928, the government repressed communist art (banning it in 1934) and the American occupation government would censor fascist and nationalist works.

Preston refuses to characterize these exchanges in moralistic or narrowly political terms (via such words as “theft” and “appropriation”). Instead, she illuminatingly examines the approaches of an international network of individual artists, scholars, and patrons with differing personal ambitions, ideological agendas, and aesthetic outlooks. Her liberal, feminist, and queer-friendly sensibility is evident, yet she is too intellectually curious (and flexible) to embrace rote identity politics. Instead, she is stimulated by contradictions.

The author is also modest. Preston says little about her own involvement in the kind of creative cross-pollination examined in her book — she doesn’t even hint at her own splendid experiments in Modernist Noh. Her Zahdi Dates and Poppies, which Theatre Nohgaku premiered this past spring at Boston University, is easily one of the finest new plays I have seen this year.

Ian Thal is a playwright, performer, and theater educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. One of his as-of-yet unproduced full-length plays was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. He is looking for a home for his latest play, The Conversos of Venice, which is a thematic deconstruction of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Formerly the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report.

Tagged: and Journeys in Teaching, Carrie J. Preston, Columbia University Press, Ezra Pound, Learning To Kneel: Noh, modernism

@KeikoInBoston contacted me to question my use of the word “cancelled” in my brief mention of the Kimono Wednesdays controversy at the MFA. I was using the term to refer to the cancellation of the element that was considered the most controversial: the trying on of the replica uchikake. From Keiko’s perspective, that was seen as an over-simplification.

Keiko provided a link to an entry on her own blog, Japanese-American in Boston that addresses some of the myths that arose around the controversy last year:

http://japaneseamericaninboston.blogspot.com/2015/07/myths-and-facts-about-kimono-wednesdays.html

I finally had a chance to see and review “At The Hawk’s Well”, the William Butler Yeats play that features so prominently in Preston’s account. The seven years between reading about it and seeing a performance was well worth the wait:

https://washingtoncitypaper.com/article/606513/irish-myth-and-tragedy-in-three-by-yeats/