Opera Album and Video Review: The Baroque Does the Bible

By Ralph P. Locke

Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s 1686 David and Jonathan brings ancient characters to life in this 2022 Chateau de Versailles production, brilliantly staged, danced, sung, and played.

David et Jonathas, Marc-Antoine Charpentier

Caroline Arnaud (Jonathas), Reinoud Van Mechelen (David), François-Olivier Jean (the Woman of Endor), David Witczak (Saul), Antonin Rondepierre (Joabel), Geoffroy Buffière (Ghost of Samuel).

Ensemble Marguerite Louise, cond. Gaétan Jarry.

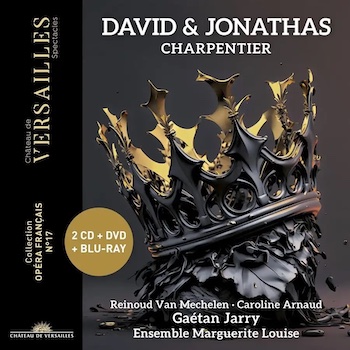

Chateau de Versailles Spectacles 102 [2 CDs + DVD + Blu-Ray] 119 minutes for the audio recording [132 minutes for the video version, whether DVD or Blu-Ray]

To purchase, click here.

This Charpentier is not Gustave (composer of the long-famous 1896 opera Louise) but a composer who was, if anything, even more important historically: Marc-Antoine (1643-1704). Charpentier was a major figure in the development of French Baroque music, including oratorios (analogous, to some extent, to those that had recently been composed in Italy by Carissimi). His works have become familiar to concertgoers in the Boston area thanks to, among other things, productions by the Boston Early Music Festival; two of the resulting recordings were nominated for Grammys in their respective years, and one of them won.

The work reviewed here, David et Jonathas, is his sacred opera on the David and Jonathan story, from the biblical book of Samuel. The recording (audio and video) comes not from BEMF but from a production in the Royal Chapel at the famous Versailles palace outside of Paris. The performers include the Ensemble Marguerite-Louise under Gaétan Jarry, and an all- or almost-all-French cast. (I’m guessing in some cases, on the basis of their names.)

It was made in the course of a run of performances in November 2022, with exquisite costumes by French fashion designer Christian Lacroix and simple, flexible sets. The stage direction and choreography are delightful, touching, and superbly well rehearsed, using costumes that suggest the late 17th century while creating vivid and dramatically appropriate visual images on their own. (I watched portions of the DVD, but am primarily reporting on the 2-CD audio contained in the same box as the DVD and Blu-Ray discs. The video version is also available for streaming on medici.tv. and excerpts, including the whole Woman of Endor episode, can be viewed on Youtube.com.)

The genre of sacred opera is hard for many of us to get our heads around. For one thing, explicitly religious topics were long forbidden in opera houses, so the standard repertory has ended up containing very few operas about, say, bible characters or saints. For another, many of us have in our minds well-defined images of this or that religious figure (e.g., Michaelangelo’s statue of a young David), and these may clash with whatever we are hearing and seeing when one of the few such works is staged.

By contrast, sacred drama, whether spoken or sung, flourished in Jesuit schools during the Baroque era, giving us such fascinating works as Kapsberger’s full-length opera-cum-pageant about the missionary work of Saints Ignatius and Francis. (Its long title begins Apotheosis, or Consecration…. The first and only recording, an excellent one, was made in 1999, featuring countertenor Randall Wong and other major early-music specialists. In an online article I discuss the messages that Kapsberger’s remarkable work, and its elaborate costuming and staged action, conveyed at the time about such lands as Palestine, India, and China.)

Reinoud van Mechelen (David) in the Chateau de Versailles Spectacles production of David et Jonathas. Costumes by fashion designer Christian Lacroix. Photo: Agathe Poupeney

Charpentier’s David et Jonathas is another such work, composed for performance at the Jesuits’ École Louis-le-Grand in 1686, where the students were often sons of influential aristocrats. The work was performed there at least twice, apparently with many listeners present (especially at the performance that coincided with the distribution of prizes). It was also performed a few years later at other Jesuit institutions.

The opera’s prologue and five acts alternated with those of a spoken play in Latin telling more or less the same story. As OxfordMusicOnline puts it: “the two works are interwoven with one another in such a way that the opera provides a lyrical reflection on the actions (and their consequences) that take place in the Latin tragedy.” Put another way, the musical numbers enlarge upon the events, giving them emotional resonance, much like highly artful book illustrations. This is particularly clear in David’s deeply moving eight-minute Act 1 soliloquy scene, in which he bewails his having been banished by the envious King Saul and begs Heaven to protect his dear friend Jonathan, who is King Saul’s son; and in Jonathan’s equivalent Act 4 lament when David regretfully must part from him.

The singers and instrumentalists were presumably all male, though the booklet-essay proposes that an experienced female singer may have been brought in for the demanding role of Jonathan, which would have greatly challenged a schoolboy. Here adult female sopranos play Jonathan and Saul’s daughter Mikal (David’s future wife). Jonathan’s devoted friend and perhaps lover David — one can read the biblical story many ways!—is taken by a marvelous high tenor, Reinoud Van Mechelen, whereas the role (in the prologue) of the Woman of Endor, who, at Saul’s command, calls up the Ghost of Samuel, is taken by a countertenor.

François-Olivier Jean (La Pythonisse) in the Chateau de Versailles Spectacles production of David et Jonathas. Costumes by fashion designer Christian Lacroix. Photo: Agathe Poupeney

(Last week I reviewed here Carl Nielsen’s 1902 opera Saul and David, which likewise contains a Woman of Endor episode, but puts it at its proper place in the tale, just before the battle that Saul will lose and in which his son Jonathan dies, leading the already-unhinged monarch to commit suicide. Handel and Jennens did the same thing in their marvelous 1738 dramatic oratorio Saul.)

The bulk of David et Jonathas is carried out in orchestra-accompanied arias, with purely instrumental numbers at the beginning of all five acts and at the end of three of them. As is typical also of secular operas from late-1600s France, the recitations between the arias are largely accompanied by the orchestra, though there are passages where only the basso continuo assists. A choral group and choral soloists appear from time to time, representing the Israelite people — for example, exulting in a military victory or welcoming David’s return and his rejoining his dear friend Jonathan. Because the orchestra and chorus are heard so extensively, as I said in regard to an opera by Desmarest, one can put a CD of a French Baroque opera into one’s machine and be certain to hear lots of shapely singing and colorful orchestral playing, even if one is not trying to follow the plot.

The playing here is first-rate, with some colorful percussion added for supernatural effect in the prologue. The chorus is splendid. Ensemble Marguerite-Louise was founded by conductor Jarry and is named a much-admired professional singer who was the cousin of the major Baroque-era composer François Couperin.

The solo singing ranges from good to spectacular. I must repeat the encomium that I bestowed on tenor Reinoud Van Mechelen in my reviews of operas by Rameau and Méhul. Here he is again surrounded by mostly fine singers, most notably soprano Caroline Arnaud (in the role of Jonathas). Baritone David Witczak is persuasive as the anxious, agonized, envious Saul, but his tone has a slight shudder, his low notes are weak for this role, and he often sounds a tiny bit flat. The Ghost of Samuel likewise lacks fullness at the bottom. François-Olivier Jean (Woman, or, in some translations, “Witch,” of Endor) is capable vocally, but, like Witczak, more impressive if you can see his (“her”) acting in the video. Smaller roles (as in scenes involving exchanges with the chorus) are handled extremely well, though occasionally, yes, weak on lower notes. This is a general tendency nowadays, termed “The Disappearing Low End” in Conrad L. Osborne’s insightful book Opera as Opera.

The work is already, it should be said, well served on disc and video. There has been much praise for a recording that was conducted by William Christie 23 years ago that used two remarkable countertenors: Gérard Lesne as David and Dominique Visse as the Woman of Endor. I enjoyed a fine, somewhat small-scaled one from Australia (ABC Classics, 2009; now on YouTube, entire). And, way back in 1982, there was one conducted by Michel Corboz that featured soprano Colette Alliot-Lugaz and two renowned countertenors: Paul Esswood and René Jacobs (the latter now known more as a skillful and imaginative conductor). Tempos in 1982 were more sedate than what we would get in all subsequent recordings (including the present one), but that paid dividends in some gloriously expansive choral movements.

Caroline Arnaud (Jonathas) and Reinoud van Mechelen (David) in the Chateau de Versailles Spectacles production of David et Jonathas. Costumes by fashion designer Christian Lacroix Photo: Agathe Poupeney

William Christie made a second recording, this time on video (2012), with Dominique Visse again as the “Woman of Endor,” but now with a true high tenor as David: Pascal Charbonneau. (The Australian recording was the first to use a tenor in the role, quite convincingly: Anders J. Dahlin.) John Barker, in his review in American Record Guide, loved this second Christie performance when he had his eyes closed, but otherwise said that, because of its intrusive and anachronistic costumes and conceptually misguided stage direction, the DVD “is best bypassed.” He recommended Christie’s 2000 audio recording, as do I, but I should stress that there are wonderful moments in the Corboz and Australian recordings as well, and of course in this new one. Barker, interestingly, didn’t object to Christie’s team having decided, in the DVD, to move the Woman-of-Endor prologue into its chronological place, near the end of the narrative. (By the way, the Woman of Endor is called, in French, La Pythonisse, by analogy to the soothsaying priestesses of the Greek god Apollo. Despite how the name looks, there is no snake in Charpentier’s opera, nor was there one in the Bible story.)

In short, the new recording is often as skillful and perceptive as any of the previous ones and very much to be welcomed. It comes with excellent booklet-essays. The libretto is sometimes translated too literally (an “haute-contre” is not a “countertenor” but a high tenor singing in his natural voice) and has been poorly edited: for example, three closing quotation marks and one open bracket in the essay are missing — as it took me a while to figure out — and “terror,” at one point, got turned into “tenor.” Even worse, on the DVD the English subtitles showed up only sporadically. I was forced to refer to the booklet to see what people were singing. I hope that this technical glitch is specific to my old DVD player, though I don’t recall it happening on other DVDs that I own. I trust that it doesn’t disfigure the version being streamed on medici.tv.

I encourage people to explore this fascinating work, using any of the fine recordings or videos now available. In an ideal world, the present release would have also provided the surviving six-page summary of the Latin play. (The full script is, alas, lost.) This would have helped us understand how two vastly different theatrical “takes” on the same story alternated in performance. I hope someone puts that official summary up online!

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: David et Jonathas, Ensemble Marguerite-Louise, Gaétan Jarry