Opera Album Review: Meyerbeer’s Disturbing Look at a Demagogue, “Le Prophète” (1849) — at Bard Summer Festival and on a New Recording

By Ralph P. Locke

Long one of the most-performed French operas, Le Prophète, thanks to some splendid performances, feels as vivid and relevant as ever.

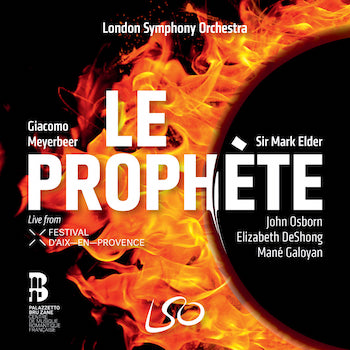

Giacomo Meyerbeer, Le Prophète

Mané Galoyan (Berthe), Elizabeth DeShong (Fidès), John Osborn (John of Leyden), Valerio Contaldo (Jonas), Edwin Crossley-Mercer (Oberthal), Guilhem Worms (Mathisen), James Platt (Zacharie).

Lyon Opera Chorus, London Symphony, cond. Mark Elder.

LSO 894 [3 CDs] 196 minutes

Click here to purchase or try any track.

It was big news for lovers of French music when the Bard Music Festival announced that Berlioz was the composer (and remarkable music critic and memoirist) selected to be the central figure of the festival this summer. And that Le Prophète, the third of the four French Grand Operas by Giacomo Meyerbeer, a composer Berlioz greatly admired, will be given a series of five performances (July 26-August 4).

It was big news for lovers of French music when the Bard Music Festival announced that Berlioz was the composer (and remarkable music critic and memoirist) selected to be the central figure of the festival this summer. And that Le Prophète, the third of the four French Grand Operas by Giacomo Meyerbeer, a composer Berlioz greatly admired, will be given a series of five performances (July 26-August 4).

The Meyerbeer performances will be livestreamed, so for a mere $20 you can experience the work in the comfort of your home or car (but please keep your eyes on the road!). And the tagline that Bard is using about the opera is quite accurate: “Religion, power, ego, and manipulation collide in Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète!”

(Coordinated with the Festival is the release of a book from the University of Chicago Press, Berlioz and His World, with chapters touching on selected major works by Berlioz — such as La Damnation de Faust and Les Troyens — and also on Donizetti and other figures with whom Berlioz was in contact or against whom he measured himself. It’s bargain-priced at $35. I co-authored, with Jürgen Thym, a chapter dealing with the renowned pianist-composer Ferdinand Hiller and his uniquely important 80-page essay on his lifelong friend Berlioz — a text that we are translating entire for the first time for publication elsewhere.)

Le Prophète is clearly having a “moment” right now, because a live CD recording of it, with the London Symphony Orchestra under Mark Elder, has just been released. I’ll focus here on the recording — the most important commercial release that the work has received since the one close to 50 years ago (1976), which was stylishly conducted by Henry Lewis and featured Renata Scotto, Marilyn Horne, and James McCracken, all in fine mid-career form. There was also a slightly earlier (bootleg) recording featuring Horne and Nicolai Gedda (which is how I first learned the work) and a commercial one conducted by Giuliano Carella. The latter, released in 2018, featured the tenor heard here, John Osborn, but the other leading roles were less impressively cast than in other recordings. Osborn also performs in a video of a 2017 production in Toulouse, currently viewable on YouTube. (Kate Aldrich is the fine Fidès there.)

The new recording, made during a single performance at the Aix-en-Provence Festival, gives current listeners and purchasers a fresh opportunity to know this major yet, today, rarely staged work. Critics who attended the Aix performance called it “a night to remember” and said that “it would be tragic if a recording were not forthcoming” — and now here it is! (Click here to purchase or to try any track.) To sum up my evaluation in advance, the work comes across with freshness, high command, and much nuance, though the secondary characters could have been assigned to better or more appropriate singers.

Meyerbeer’s stage works are skillfully crafted, in their librettos (mostly by Eugène Scribe) and music alike, and they can be enormously effective. They were rightly praised at the time for combining some of the best features of Italian music (captivating vocal lines that sometimes sprout coloratura passages), German music (harmonic sophistication, developmental treatment of themes and motives), and French music (varied and nuanced treatment of orchestral color, not least by incorporating the latest advances in the construction of woodwind and brass instruments).

His four French Grand Operas, in particular, also ask for elaborate sets, costumes, and onstage movement and involve a large singing cast. Thus productions nowadays remain rare. We mostly get to know the works through audio-recordings (or, rarer still, videos). I have long cherished my LP and CD versions of those four works: Robert le diable (starring Samuel Ramey), Les Huguenots (starring Joan Sutherland), Le Prophète (the Henry Lewis recording that I have mentioned), and L’Africaine (with Shirley Verrett and Plácido Domingo), and of his comic opera Dinorah (with soprano Deborah Cook). I have also greatly enjoyed parts of, if not everything in, various video releases. In addition, I’ve reviewed here some lesser-known but remarkably fluent and engaging Meyerbeer works: three from early in his career when he was living and working in Germany and Italy (Alimelek, Jephthas Gelübde, and Romilda e Costanza) and L’Étoile du nord, a comic opera that had its Paris premiere five years after Le Prophète. Early this year, I was delighted to welcome a marvelous new recording of the aforementioned Robert le diable, starring, yes, tenor John Osborn.

Now we have this new recording of Meyerbeer’s third grand opera, an amazing work that set the opera world ablaze in 1849 and that remained a staple in the repertory into the early 20th century. Music lovers tend to know only a few numbers from it — most notably the Act 4 Coronation March and, in Act 3, the four-movement ice-skating ballet (originally done on roller skates). But several solo numbers for Jean and for his mother Fidès are enormously compelling and memorable, my favorite being the alternatingly desperate and energetic Act 5 soliloquy (in prison) in which Fidès denounces the Anabaptists as “priests of Baal” and exhorts Truth to strike Jean and force him to admit that he was born to her (and thus is not, as he is claiming, God’s son, born of no woman).

Elizabeth DeShong — a firmly voiced and persuasive Fidès. Photo: Facebook

Fortunately, the performance is in the highly experienced hands of Mark Elder, the renowned English conductor who was musical director of English National Opera for 14 years. Here he conducts one of the world’s great orchestras, the London Symphony, whose wind players, in particular, demonstrate conspicuous mastery and sensitivity in solo passages strewn throughout the work. I have previously stayed away from “LSO Live” recordings because the acoustics tend to be generalized, as if the microphones were too far away from the orchestra. But here I was able to grasp all kinds of wonderful details in Meyerbeer’s skillful instrumental writing, while also following the debates among the opera’s skillfully drawn and quite interesting characters: the demagogue Jean de Leyde (John of Leyden, a historical character from the early 16th century but one who feels as disturbingly real as certain politicians on our TV screens), his principled and devoted mother Fidès, his long-suffering fiancée Berthe (who becomes either unhinged or a heroic terrorist, depending on your point of view), the vicious ruler and womanizer Oberthal (another all-too-familiar type), and, perhaps most intriguing of all, the trio of Anabaptists (Jonas, Mathisen, and Zacharie), who lure Jean into their conspiracy by making him believe that he is a kind of Christ reborn. (After coming under their influence, he ends up singing in an eerie half-voice: “Je suis le fils de Dieu.”) Moment after moment, I understood why Le Prophète held the stage for so many decades and, more significantly, I felt its continuing resonance and relevance.

The main singers here put the work across fluently and convincingly. Elizabeth DeShong, whom I praised in Mercadante’s amazing Il proscritto, and who has taken major roles at the Met, is, much like Marilyn Horne before her, a firmly voiced and persuasive Fidès, the single most distinctive role in the opera (and a palpable influence on Verdi’s Azucena in Il Trovatore). Armenian-born and -trained lyric soprano Mané Galoyan (the Berthe here) is a new name to me: she and John Osborn both show a natural grasp of French style and an ability to shift smoothly from delicate to stentorian singing and back, touching all kinds of gradations along the way. Galoyan’s brief passages of coloratura, I should add, are tossed off with exquisite ease (as are DeShong’s!).

The secondary roles are handled capably but with less distinction. As the villain Oberthal, Edwin Crossley-Mercer, whom I described as “solid” but “prosaic” in Rameau, comes across, in this heavily scored work from more than 100 years later, as dramatically alert but vocally lightweight: in no way a match for the great Francophone actor-singer Jules Bastin on the Henry Lewis recording.

The three Anabaptists are likewise disappointing compared to the equivalent trio on the Lewis recording, who were two native Francophones — Jean Dupouy and Christian Du Plessis — and the Met’s redoubtable basso Jerome Hines. The Anabaptists should sound as if they have wandered in from a comic opera, in order to then surprise the audience when the three become viciously disloyal to Jean. Put differently, we should enjoy the men’s larkiness and then feel the rug being pulled out from under us, making us, too, feel implicated in this opera’s complex and all-too-realistic moral morass.

The booklet that comes with the recording is a mixed bag. The essay by musicologist Étienne Jardin is first-rate as far as it goes, but it does not explain which edition is used here. Apparently it’s the scholarly edition of 2011, as heard in the Carella recording, but now a few passages have been deleted in order to move the action along. Interested readers will want to consult Mark Everist’s detailed review of a 600-page book that came out more or less in tandem with the critical edition.

Mark Elder and soloists in the concert version of Le Prophète at the Aix-en-Provence festival in 2023. Photo: Vincent Beaume

Likewise clear and helpful are the briefer essays on the work, the composer, and the librettist. Sue Rose, the translator, generally handles her task well. But she sometimes slips: a “fanfare de saxhorns” becomes a “saxophone fanfare,” even though the French word “fanfare” (in the present context) means a group of brass instruments — not, as readers will assume, a short annunciatory musical call. Saxhorns are valved brass instruments, related to the euphonium and so on, whereas saxophones are reed instruments that, though made of metal, produce a sound wildly different from that of saxhorns. The translator’s confusion presumably derives from the fact that all these instruments were named after the same maker, Adolphe Sax. But keeping facts straight is part of a translator’s responsibility! Similarly, she calls Jean a “visionary” — which sounds praiseworthy in English — when the essay-writer (Jardin) clearly means something like “a man trapped in delusions.”

As for the libretto, I am glad that the booklet offers it in both French and English. (The Carella recording has it in French and German.) But I noticed far too many glaringly literal renderings, in which a word that looks similar in English is automatically chosen, and French word order is maintained. Sometimes the meaning is simply wrong, such as (in the final scene) mention of “its ruin,” where “his ruin” — i.e., Jean’s imminent death — is clearly meant; or the galloping of “messengers” (whereas “coursiers” in 19th-century literary texts generally means horses or steeds — indeed, nobody is carrying messages in this scene). Similarly, “the pardon of God” sounds as if somebody is letting the Divinity off the hook, whereas, in idiomatic English, one would speak straightforwardly of “God’s forgiveness.” Meyerbeer’s opera and this generally fine (-to-splendid) performance deserve better.

The inept translation, perhaps wisely, is uncredited. Surely there are underemployed college graduates in London who would have been able to translate Scribe’s French better than whatever machine (I suspect) was chosen for the task here.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is part of the editorial team of Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal, an open-access source that includes contributions by performers (soprano Elly Ameling) as well as noted scholars (Robert M. Marshall, Peter Bloom) and is read around the world.

An altogether illuminating discussion of the work and the comparative merits of the various available recordings. I hope Locke will be able to provide a review of the Bard production.