Opera Album Review: Hot News — Award-Winning First Recording of a Major Contemporary of the Young Verdi

By Ralph P. Locke

The whole recording reminds me that numerous forgotten but extremely accomplished nineteenth-century works can provide rich satisfactions when performed as well as this.

MERCADANTE: Il proscritto.

Sally Matthews (Anna Ruthven), Irene Roberts (Malvina Douglas), Elizabeth DeShong (Odoardo Douglas), Ivan Ayon-Rivas (Arturo Murray), Ramón Vargas (Giorgio Argyll), Goderdzi Jandelidze (Guglielmo Ruthven).

Opera Rara Chorus, Britten Sinfonia, cond. by Carlo Rizzi.

Opera Rara 62 [2 CDs] 125 minutes.

Click to purchase, to preview any track, or to hear it entire on YouTube.

Let’s start with the hot news: an opera by a contemporary of the young Verdi, Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870), has just won an award for Best Opera Recording of the Year, from the 2023 International Opera Awards. “Saverio who?” some may reasonably ask…

Let’s start with the hot news: an opera by a contemporary of the young Verdi, Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870), has just won an award for Best Opera Recording of the Year, from the 2023 International Opera Awards. “Saverio who?” some may reasonably ask…

Well, opera lovers have probably read about Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870), but we have rarely had a chance to see his stage works. Previous recordings have featured his works for flute (especially concertos), a clarinet concerto, and some sacred works, but, of his nearly sixty operas, only a few have been recorded, notably Il bravo and I briganti, as well as, on the Opera Rara label, Zaira, Virginia, and highlights from Maria Stuarda.

Some of his operas attained great success when first staged, achieving more performances than certain operas that the young Verdi wrote around the same time or a little later. But many people objected to the “reforms” that he proudly introduced into his operas, reforms inspired by the French grand operas of Meyerbeer and Halévy. These included having more fluidly constructed librettos (not ones built heavily on long parallel stanzas that a composer would then set to more or less the same music), greater involvement of the chorus, more varied harmony, and richer and more varied orchestration.

Il proscritto, to a strong libretto by the skillful Salvatore Cammarano (who had provided the text for Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor), was first performed in 1842 in the San Carlo theater in Naples, the one for which Rossini had written a series of important serious operas in the years 1815-22. Like some of those Rossini operas, Il proscritto has parts for two tenors, one higher-flying, the other more muscular-sounding and intense. The brawnier of the two tenors in such operas is the forerunner, in a way, of the passionate baritone roles that Verdi would develop, such as Count di Luna in Il trovatore.

The action takes place in a castle near Edinburgh in the seventeenth century. The French play on which the opera was based was set in Grenoble in 1816, but this would have risked creating problems with the politically cautious Italian censors.

Malvina’s husband Giorgio is reported to have died in a shipwreck. Malvina is encouraged by her mother and her half-brother Guglielmo to accept Arturo as her new husband because of his political position: he is a Cromwellian, whereas Giorgio was a royalist. Odoardo has a repeated function as his sister Malvina’s loyal confidant and defender, and as someone who also wants to protect Giorgio. (The latter had earlier saved the life of Odoardo’s and Malvina’s father.)

Giorgio returns, though at first disguised and much altered by time and travail. Malvina, who alone recognizes him, at first shrieks aloud, but does not reveal to his identity to the others.

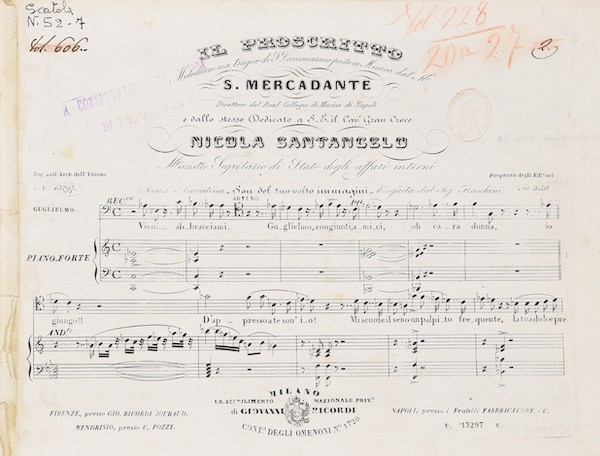

The first page of Mercadante’s Il proscritto.

Giorgio eventually admits to being somebody whom Malvina knows. He and Malvina, finally left alone, engage in a highly dramatic duet, for his return has put her in an impossible situation: she has come to love Arturo, and indeed has married him (just before Giorgio’s unexpected return).

There are some further plot-twists: for example, Guglielmo tries to get the suspicious stranger arrested and taken off to Edinburgh. The opera ends with a touching death scene for Malvina, who has taken poison rather than return to Giorgio and flee with him as he demands; she expires, pledging to Arturo that she and he will meet in Heaven.

Il proscritto was deemed a success, surely in part because it was written to suit the abilities of the singers available that season. But those singers were a somewhat odd (or maybe interesting) assortment by standards of the day. In addition to the two contrasting tenors, the opera included two leading roles for lowish-voiced female singers: a mezzo (Malvina) and a contralto. The latter is a pants role: Malvina’s brother Odoardo.

The only somewhat prominent soprano role is that of Anna, who is the mother of Malvina and Odoardo and also, by a previous husband, of Guglielmo (a bass role). Finding an opera company that had two leading tenors (especially given that Romantic baritones were becoming a standard fixture) and two leading lower-voice women was a challenge, and the opera fell out of the repertory. (The singer of the role of Anna heads the cast list in my header only because I have arranged it by voice type, from high to low, as I generally do.)

Now along comes Opera Rara, whose imaginative team of performers and scholarly advisors has, since 1970, brought over 60 nineteenth- and early twentieth-century operas, notably by Donizetti and by Offenbach, to the attention of music lovers, through concert renditions in London and through recordings that have generally received rave reviews. Often the singers are youngish, with voices still firm and true, not rough or wobbly from overuse in large halls.

Conductor Carlo Rizzi with singers Ramón Vargas and Iván Ayón-Rivas performing Mercadante’s Il proscritto at the Barbican Hall in 2022. Photo: Russell Duncan, via Opera Rara

Such is the case here: as a photo in the booklet quickly reveals, the cast consists mostly of people who are in their late 20s, 30s, or 40s. The one notable exception, the internationally renowned Ramón Vargas (at age 61), sounds as marvelous as ever, no doubt for having resisted any temptation to take on certain bigger roles. Particularly astounding is Elizabeth DeShong, who reminds me of Marilyn Horne in her prime, embellishing the written notes in such a way that (as a critic said of Horne) one never knows from which of three octaves the next note is going to come. New to me but marvelous throughout are Irene Roberts (born 1983), in the linchpin role of Malvina, and Ivan Ayon-Rivas (born 1993), as the man she has grown to love.

With Carlo Rizzi on the podium, the result is delightful, touching, and idiomatic from beginning to end. The excellent acoustics (the recording was made in London’s Henry Wood Hall) allow us to hear, in a natural balance, many notable imaginative orchestral touches, such as an aria with repeated incursions of a solo clarinet (liquidly conveyed by, if I can guess from the list of players, Joy Farrall), occasional departures from the four-bar structuring that can otherwise become a bit predictable in Italian (and other) operas of this era, and some harmonic surprises and enlivening commentary from the string section or brass.

Even more important, the music is consistently attractive, with many memorable tunes. (Scholars tell us that Il proscritto was a conscious attempt on Mercadante’s part to bring back a certain melodic straightforwardness after several operas that were more consciously “reformist.”) The several duets for various of the main characters, and the extended act-finales, carry the drama forward in imaginative ways, as helpfully explained in Roger Parker’s helpfully detailed booklet-essay.

Elizabeth DeShong, Irene Roberts and Carlo Rizzi performing Mercadante’s Il proscritto at the Barbican Hall in 2022. Photo: Russell Duncan, via Opera Rara

Certain scenes could be presented effectively on their own. If I were helping to put on a concert that included Brahms’s Alto Rhapsody, I would be tempted to ask the contralto to do, as well, Odoardo’s wonderfully rich, multi-sectional scene from the middle of Act 2 (which begins with a stirring chorus of political exiles): seventeen highly characterful and contrasted minutes of music that would grab the listeners and likely lead them, at the end, to erupt in cheers.

The whole recording reminds me that numerous forgotten but extremely accomplished nineteenth-century works can provide rich satisfactions when performed as well as this. The booklet includes insightful essays by Teresa Poggiali on the libretto and (as mentioned) by Roger Parker on the music and the work’s performance history. Parker also made the superb translation of the libretto and can be heard online discussing the process of bringing this important opera back to life. This is how all unfamiliar works should be brought to the public.

I urge record collectors to explore Opera Rara’s latest efforts. And also earlier ones, some of which are being re-released now, though often without the detailed booklets that the original LPs or CDs included.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.