Opera Album Review: The Young Meyerbeer, in a Biblical Opera, Reveals His Musico-Theatrical Imagination

By Ralph P Locke

A captivating world-premiere recording of a work by the 21-year-old who would later conquer the operatic world with Les Huguenots and L’Africaine.

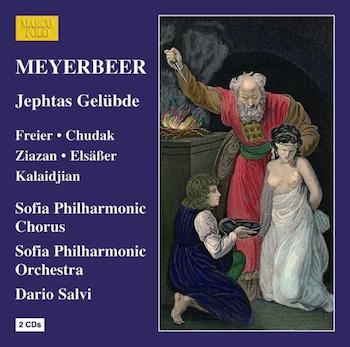

Meyerbeer: Jephtas Gelübde (Jephthah’s Vow)

Andrea Chudak (Sulima), Marcus Elsaesser (Asmavett), Laurence Kalaidjian (Abdon), Soenke Tams Freier (Jephta).

Sofia Philharmonic Chorus and Orchestra, cond. Dario Salvi.

Marco Polo 8.225383-84 [2 CDs] 157 minutes.

To purchase or try any track click here.

Here is a world-premiere recording of one of Meyerbeer’s earliest operas, from 1812, when he was a mere 21 years old. It already reveals remarkable facility and control, with elegantly shaped melodies well suited for singing, and with frequent happy intrusions from solo wind or string instruments in the orchestra. (See my review of his other “first” opera, Alimelek, which he began before this one but which didn’t get performed until after it. That one is based on a tale from the Thousand and One Nights.)

Here is a world-premiere recording of one of Meyerbeer’s earliest operas, from 1812, when he was a mere 21 years old. It already reveals remarkable facility and control, with elegantly shaped melodies well suited for singing, and with frequent happy intrusions from solo wind or string instruments in the orchestra. (See my review of his other “first” opera, Alimelek, which he began before this one but which didn’t get performed until after it. That one is based on a tale from the Thousand and One Nights.)

The title in German is Jephtas Gelübde, and the libretto is by Aloys Wilhelm Schreiber (whose name means “scribe”!). The plot expands upon a brief, troubling tale in Judges 11:30-40: Jephthah, an Israelite judge and military leader, vows that, if his troops vanquish the invading Ammonites, he will sacrifice by fire “whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me.” Jephthah returns victorious, and his daughter comes out to welcome him “with timbrel and dance.” He is distraught. She implores him to grant her two months in which she will go, with her companions, to the hills to “bewail my maidenhood” (i.e., mourn that she will not live a full life). He agrees and eventually carries out the vow.

Schreiber’s libretto greatly expands and tweaks the biblical story. Jephthah’s daughter here has a name, Sulima, and of course is a lyric soprano. She has two suitors: Asmavett (tenor), whom she agrees to marry if he will but distinguish himself through bravery in the war, and Abdon (baritone), a tribal leader who swears to be avenged on his rival-in-love Asmavett. (In this paragraph I incorporate wordings from, and paraphrase, Robert Letellier’s fine synopsis in the booklet.) The climax comes in Act 2, when Jephthah returns victorious and Sulima rushes to meet him. The opera ends with a major change to the biblical narrative: as a death march announces the entry of Sulima to the Temple to be sacrificed, the High Priest proclaims a divine revelation: God does not demand the blood of human sacrifice. The people sing praises of the Lord. The same kind of switcheroo will happen nine years later in Der Freischütz, the pathbreaking opera by Carl Maria von Weber (who, along with Meyerbeer, had studied with the noted pedagogue Georg Joseph Vogler).

Letellier’s informative booklet-essay argues that Meyerbeer’s opera features an “extraordinary” use of leitmotif; this would make the work an unconscious predecessor of Wagner’s Ring Cycle. But I was more struck by the fact that this work is largely, and quite unlike Wagner’s operas, a German Singspiel, in the manner of Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio and Beethoven’s Fidelio (1805, rev. 1814). Furthermore, the vocal lines are studded with the coloratura typical of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, in German operas as well as French and Italian ones.

A detail from Edwin Longsden Long’s 1885–1886 painting “Jephthah’s Vow: The Return.” Photo: Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum

The musical numbers are often gentle and tuneful, even folklike (at least early in the work). There are also immensely appealing orchestral numbers toward the end of Act 2: a percussion-laden triumphal march (as Jephthah and the soldiers return) and a “Dance of the Maidens” to welcome the victors. The dance makes intriguing use of a “hopping-third” figure that was often associated at the time with the Middle East. Presumably Meyerbeer was thinking of the Bible lands as being equivalent, in some sense, to the Ottoman Turkey of his own day.

The largely pleasant atmosphere gets shattered, of course, when Jephthah sees Sulima approaching him and realizes that his vow to God was hasty and unwise. This moment felt very dramatic in the recording, because Meyerbeer had so successfully set up a prevailing atmosphere of merriment and rejoicing.

The rest of the opera takes a more serious tone, as Sulima, Asmavett, and Jephthah all bemoan what may happen, with Jephthah praying that he himself die soon after his daughter, Abdon declaring (privately, and in part through “melodrama”: speech over orchestral music) that he is getting his revenge on a woman who rejected his “manly love,” and Asmavett insisting that, if they want to shed her innocent blood, they must kill him first. Two groups of soldiers take, respectively, Abdon’s and Asmavett’s side in the debate. Jephthah, with a heavy heart, prepares to kill Sulima himself, but the High Priest arrives and declares God’s will: Jephthah’s vow must be set aside since he has proven himself obedient, as did Abraham when instructed to kill his beloved son Isaac.

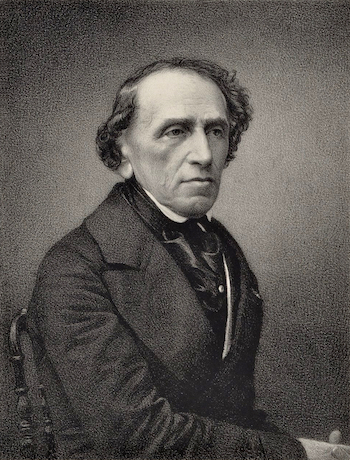

Giacomo Meyerbeer. Photo: Wiki Common

The performance is quite capable, with solid vocal renditions from the four main characters (all of them native German-speakers), though sometimes afflicted by a slow vibrato or wobble. The Asmavett is often scrawny in sound or not quite on pitch, but, surprisingly, clarion in his high register. (He sounds quite good, like a fine light-opera tenor, in the duet with Sulima that the record company has excerpted on YouTube.) The minor characters vary more in ability. Sulima’s confidante, Tirza, is played by Ziazan, a singer who goes by that single name and has an unusually wide range but an acidic tone. The spoken dialogues are vividly rendered and are miked clearly, almost as if for a radio performance.

The Italian-Scottish conductor Dario Salvi makes a specialty of recording unusual repertory. I was not impressed by the performance he led of a Goethe-based opera by Ingeborg von Bronsart (with some of the same singers), but here he seems very savvy and in control, and has better music to work with. The Bulgarian orchestra and chorus are highly proficient, and the winds play in an international manner (not in any way recalling the odd ways of playing typical of Soviet-era recordings).

Anybody interested in Meyerbeer’s development, or in the development of German-language opera, will find much food for thought here — and more than an hour of lively, colorful, dramatically apposite music, delightfully rendered. Enterprising concert organizers may want to program the powerful Prelude, Recitative, and Arioso with Chorus for the anguished Jephthah that opens Act 3. It’s as wonderful as the analogous number for Agamemnon (he has likewise vowed to sacrifice his daughter in exchange for divine help) at the beginning of Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide (1774), and that’s saying a lot!

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Dario Salvi, Jephtas Gelübde, Jephthah’s Vow, Marco Polo Records