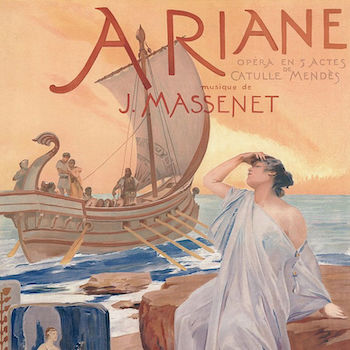

Opera Album Review: A Resplendent First Recording of a Forgotten Opera by the Composer of “Manon” and “Thaïs”

By Ralph P. Locke

With Egyptian-born Amina Edris in the title role, Massenet’s opera engages the musical and theatrical imagination with its rich characterizations of Greek mythic adventures.

Ariane, Massenet

Amina Edris (Ariadne), Kate Aldrich (Phaedra), Judith van Wanroij (Cypris and two other roles), Julie Robard-Gendre (Persephone), Jean-Francois Borras (Theseus), Jean-Sébastien Bou (Pirithous).

Bavarian Radio Chorus, Munich Radio Orchestra, cond. Laurent Campellone.

Bru Zane [3 CDs] 163 minutes.

To purchase, click here. Individual tracks can be heard on YouTube even without a subscription.

The opera world and, even more so, music critics and historians have not known what to do with Massenet. The works — including such oft-performed ones as Manon and Thaïs — are in many essential ways post-Wagnerian: they use multiple themes and motives that recur and get developed; the musical interest and continuity is often defined by the orchestra, with the voice above it; and the orchestra is large and colorful, with, at times, prominent and intriguingly varied brass. But (unlike in some of Wagner’s mature operas and those of certain of his followers) the vocal lines are shapely and singable: often triadic, scalar, or sequentially rising, neither declaiming in an uninteresting monotone nor — except in moments of emotional stress — wildly leaping.

The opera world and, even more so, music critics and historians have not known what to do with Massenet. The works — including such oft-performed ones as Manon and Thaïs — are in many essential ways post-Wagnerian: they use multiple themes and motives that recur and get developed; the musical interest and continuity is often defined by the orchestra, with the voice above it; and the orchestra is large and colorful, with, at times, prominent and intriguingly varied brass. But (unlike in some of Wagner’s mature operas and those of certain of his followers) the vocal lines are shapely and singable: often triadic, scalar, or sequentially rising, neither declaiming in an uninteresting monotone nor — except in moments of emotional stress — wildly leaping.

The vocal lines seem well gauged for projecting in an opera house over all that gloriously diversified orchestral sound. (No wonder that Joyce DiDonato has recorded one of the arias — she knows what “works” in a concert hall.) We may recall that Massenet established his fame, to some extent, with seven symphonic suites, from 1867 to 1882, including ones in Hungarian and Alsatian styles, as well as one evoking the world of “fairytale.” Massenet’s harmonic language can be quite varied, but it always offers a clear tonal center, even if the scale and chords being exploited are not the fully traditional ones of conservatory-approved major and minor. In the work under review, Ariane (1906, six years before the composer’s death), I loved several passages in which the voice outlined a juicy added-sixth chord.

In short, the basic musical language and manner in Ariane may remind you of, say, early Fauré or early Debussy. Or, rather, they sound a lot like early- and middle-period Massenet. And a lot like various pieces by Chabrier, Reynaldo Hahn, and other composers that we may tend not to think about much when making a mental map of French music in the generations after Berlioz. Yet Massenet lived till 1912, well into the first phases of musical modernism, writing operas, oratorios, and songs galore. As for the added-sixth chord, it remained a potent component in French music for decades to come, as in Messiaen’s voluptuous Turangalîla-Symphonie (1946-48). Hollywood film composers loved it, too, but Debussy and Massenet had given it a workout long before them.

Ariane, which has never been recorded before, was first performed at the Opéra in 1906, four years after Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande and one year after Richard Strauss’s Salome. It might thus seem a cowardly throwback, for those who believe that the art of music develops in a straight line and pushes ever forward toward new horizons: disjunctive rhythms, daring harmonies, and melodies and phrase structures that at first baffle the mind.

Composer J.Massenet — in many essential ways his operas are post-Wagnerian.

Nothing in Ariane baffles. The work, as I have already suggested, could have been composed decades earlier. I spent 2-1/2 hours delighting in its engaging flow of mellifluous sounds, and then listened again to various sections several times more. Massenet and his librettists have here cannily set up a series of scenes and events that lend themselves to musical portrayal, such that one can enjoy the experience without paying much attention to the details of the plot (as many of us, honestly, often do at times with operas by, say, Handel, Bellini, Wagner, or Puccini) and feel deeply gratified by the experience.

Or, of course, we can follow the libretto and get that much more out of the work. There are powerful musical evocations of Theseus’s combat with the Minotaur and a storm tossing a ship around, and there’s an entire act (4) in Hades, where Persephone reigns. (I give the characters’ names in their more familiar English versions.) That act is pleasantly interrupted by some delicate, poised ballet numbers not far in sound from Delibes (whose most famous works come from the 1870s-80s). The three main female roles are savvily contrasted: a lyrical soprano for the title character, a “dramatic soprano” (according to as a note in the score) for the more excitable Phaedra, and a commanding contralto for Persephone in Hades.

Thanks to skillful librettist Catulle Mendès, each act has its own shape and coherence, too, like, say, Act 2 of Puccini’s Tosca. I could easily imagine Act 2 or 3 of Ariane making a fine effect in an evening of operatic acts at a university music school or conservatory, where of course the obligatory quasi-Wagnerian orchestra would be easy to put together.

Oh, I should have outlined the plot: it’s a version of the old Greek myth of Ariadne, who loves Bacchus but he abandons her for her sister Phaedra. Phaedra is killed by a toppling statue and goes down to Hades, which Ariadne visits and, by dint of her sorrow, persuades Persephone to let Phaedra return to earth. Theseus reunites with Phaedra, and Ariadne dies, surrounded by the same wafting chorus of spirits that opened the opera.

You may know other works based on some phase of this story, including Monteverdi’s influential Lamento d’Arianna, Strauss’s kaleidoscopic Ariadne auf Naxos, or even a well-known concert overture by Massenet himself based on Racine’s tragedy Phédre. But this Ariane tells its own version well, indeed beautifully at every point. Is that what critics and historians hold against Massenet, that the music is consistently appealing?

Soprano Amina Edris. Bildquelle: © Capucine de Chocqueus

I urge listeners to give Ariane a try. And then move on to other Massenet operas that they’ve never encountered. Maybe our kneejerk support of modernism and “progress” (in music as in so much else) needs to be rethought!

The success of the work in this remarkable recording has a lot to do with the fine performance. Amina Edris, an Egyptian-born soprano who grew up in New Zealand, makes sounds of chaste loveliness as Ariadne. (I admired Edris in the recent first commercial recording of Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable.) Jean-Francois Borras, the Theseus, establishes himself as another in a string of wonderful new tenors coming out of France. Kate Aldrich chews up the scene as the ambitious Phaedra, as vividly as she portrayed Statira in Spontini’s major opera Olimpie. Edris’s duet with Alrdrich in Act 3 is perhaps the highpoint of the score, as Ariadne pleads with Phaedra to intercede on her behalf with Theseus, not realizing that Phaedra is her rival for his affections: this duet could easily stand alone in a concert featuring two sopranos of contrasting temperament (or a soprano and a mezzo), next to — or instead of — more famous duets such as Bellini’s “Mira, o Norma.”

As Theseus’s comrade Pirithous, Jean-Sébastien Bou seems more secure than he was in Salieri’s boldly imaginative, almost proto-modernistic Tarare (1787), resembling the fine singer he proved to be as Valentin in Gounod’s Faust (world-premiere recording of the 1859 first version, with spoken dialogue). Julie Robard-Gendre conveys immense authority (in part through a touch of fearsome wobble) as Persephone in Act 4’s Hades. And Judith van Wanroij, who was so marvelous in Saint-Saens’s luscious and culturally perceptive La princesse jaune, is luxury casting in three brief roles, including Cypris, the goddess who causes Phaedra to die and be sent to Hades.

The Munich Radio Orchestra sounds splendid, under the savvy control of Laurent Campellone, who must know this score better than anybody: he conducted the first modern revival at the Massenet Festival in 2007 — quite splendidly, according to a review of that production. The Bavarian Radio Chorus is utterly gorgeous as ocean spirits, a community of mourners, and the like.

The recording, made during two concert performances at the Prinzregenten Theater in Munich, is vivid and detailed. The accompanying book contains the libretto and first-rate essays, including a long appreciation by Fauré (Puccini, too, was at the premiere), all in French and excellent English translations, plus some revelatory illustrations that would have been even more effective if printed on white paper rather than cream.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Amina Edris, Ariane, Bavarian Radio Chorus, Bru Zane, Jules Massenet, Laurent Campellone