October Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Books

Brad Kessler’s 2021 novel North is a beautifully wrought chronicle of disparate lives: a Somali woman seeks asylum in Canada and is unexpectedly sheltered at a Vermont monastery. This sparks a crisis of faith; eventually she is aided by an Afghan war veteran.

While researching his fictional tale, Kessler met with a number of Somalis who had resettled in Vermont over the last 20 years. These conversations inspired the author to work with community members on a project that would preserve their stories. The result is Deep North (Onion River Press), a volume of first-person narratives that details survival and resilience. The volume contains the harrowing journeys taken by a farmer, a camel-herder, and a single mother of seven after the 1991 civil war shattered their lives. As Kessler notes in the book’s afterword, “Stories and memories: the two things they were able to carry with them when everything else was stripped from them.”

Shadir Mohamed grew up along the lower Juba River in a farming community, but fled because, as a member of the Somali Bantu ethnic minority, he was attacked. Escaping to Kenya, he spent 15 years shuttling among a succession of squalid refugee resettlements. While in the camps he married and started a family. In 1999, the US Embassy in Nairobi accepted his application for a visa, which was finally approved in 2004. He and his wife landed in Burlington with one bag between them and four children.

Abdihamid A. Muhumed was a nomadic camel-herder, constantly moving with his family between Somalia, Ethiopia, and Kenya with their animals. The civil war escalated and a gunman killed one of his brothers and father and stole their animals. He walked for weeks, wandered through the forests toward Kenya, and lived in desolate fenced-in camps with one brother and his family until, in 2008, they resettled in Winooski.

Fardusa A. Abdo and her family fled southern Somalia and relocated to Yemen. She did not attend school, staying home to do household chores. At 19 a marriage was arranged, and eventually the couple had seven children, two with disabilities. Her husband illegally crossed into Saudi Arabia to find work and was deported back to Somalia. She single-handedly raised the children. Her application to immigrate to America was approved in 2014, and they settled in Winooski.

Deep North chronicles the trauma of dislocation as well as what it took to rebuild shattered lives. The authors will be in conversation with community leader Abdirashid Hussein and editor Brad Kessler at the O.N.E. Community Center, 20 Allen Street, Burlington, VT, on October 8 at 4 p.m.

— John R. Killacky is the author of because art: commentary, critique, & conversation.

Children’s Books

Gary D. Schmidt has won lots of awards for his middle-grade and YA novels. The Labors of Hercules Beal (HarperCollins) is sure to garner the author even more. It’s funny, moving, meaningful, and beautifully written. Readers will be swept along a year-long journey with Hercules Beal, whose grief over the sudden loss of his parents in a car accident is palpable. Not only does he feel responsible for the tragedy, he has to contend with a new school, a no-nonsense teacher, an older brother (named Achilles) who has left a glamorous job as a journalist to take care of Hercules and the family horticulture business, and his brother’s Goth girlfriend, Viola.

Gary D. Schmidt has won lots of awards for his middle-grade and YA novels. The Labors of Hercules Beal (HarperCollins) is sure to garner the author even more. It’s funny, moving, meaningful, and beautifully written. Readers will be swept along a year-long journey with Hercules Beal, whose grief over the sudden loss of his parents in a car accident is palpable. Not only does he feel responsible for the tragedy, he has to contend with a new school, a no-nonsense teacher, an older brother (named Achilles) who has left a glamorous job as a journalist to take care of Hercules and the family horticulture business, and his brother’s Goth girlfriend, Viola.

Told in the first person, Hercules has a Holden Caulfield-esque voice. “So here’s the first thing,” he says, “My name is Hercules Beal. I know. It’s a stupid name…. But I didn’t choose it. So don’t blame me. Blame … my parents. Or don’t. Really, it’s none of your business.” Yet everything about him is our business. He’s a sensitive, insightful soul, who can appreciate the beauty around his Cape Cod home, loves the stray dog he adopts and the “ugly” one-eyed cat he befriends, the antics of his new friend Henry, and the tribulations of his best friend, Elly. Every morning he heads out at daybreak to watch the sun rise over the dunes, a ritual that brings him closer to the mom and dad he has lost.

At first, Hercules isn’t happy about attending the Cape Cod Academy for Environmental Science instead of Truro Middle School. To make matters worse, his teacher, a former lieutenant colonial in the Marines, assigns Edith Hamilton’s Mythology for language arts. Each student must complete a challenging, year-long assignment, and of course Hercules’s seems “predestined.” He, like his mythical namesake, must complete his own version of the 12 Labors of Hercules.

How Hercules succeeds in doing that is a story full of dramatic turns, humor, growing pains, real-life adventures, and Hercules’s own reflections, told through the narrative and the essays he writes for school. Although the plot occasionally seems overly complicated, the old adage, “it takes a village,” is wonderfully represented as Hercules learns that helping others — and having others help him — is the key to healing. As we follow Hercules on his journey, we also get a nice sampling of classical Greek mythology and a mini-lesson in what it takes to run a plant nursery business — added bonuses.

— Cyrisse Jaffee

Classical Music

Is the string quartet the most versatile ensemble and genre out there? Shatter, the Verona Quartet’s new album (Bright Shiny Things), suggests that both are at least immensely flexible. While the disc’s aims are high — to provide an “opportunity to break through and rebuild our interactions with an increasingly complex world,” as the liner notes have it — the recording also demonstrates just how durable this instrumentation is.

Each of its three pieces offer distinctive perspectives.

Reena Esmail’s Ragamala explores the intersection of Western and Indian musical traditions. Essentially nods to four types of Hindustani raags, Esmail’s score is often quite appealing to the ear, even as one might wish that the piece was infused with more of the vigorous type of writing that marks its second and fourth sections. Even so, the lyrical passagework is gorgeous and improvisatory-sounding, and the piece includes — to beguiling effect — a vocal part in each movement. The last are enchantingly sung by Saili Oak.

Meantime, Julia Adolphe’s Star-Crossed Signals investigates themes of isolation, connection, and communication. Taking its cue from the composer’s fascination with nautical signal flags, it contrasts violent, aggressive gestures and dissonant extended techniques in the first movement with gentler, quieter textures in the second. Those culminate in an apotheosis of lyrical unity that, even if it’s half-expected, proves wholly satisfying.

Michale Gilbertson’s 2016 Quartet is a personal response to that year’s presidential election. Seeking, in his words, to “write something comforting,” the composer turned to Sibelius, and the shadow of the Finnish master’s Second Symphony hovers over the opening bars of the present effort.

The structure of the Quartet’s first movement is theme-and-variations-like: contrasting materials appear, are developed, and emerge in new contexts. As in Ragamala, there’s a smart accessibility to Gilbertson’s writing; beneath an alluring surface, he delivers plenty of variety to keep the ears happy. Though the energetic finale (“Simple Sugars”) seems to bustle aimlessly, its textures are Adams-worthy.

In all three works, the Veronas (violinists Jonathan Ong and Dorothy Ro, violins Abigail Rojansky, and cellist Jonathan Dormand) play with gusto. Even at the most frenetic moments, like the tortured climax of Star-Crossed Signals or the finale of the Gilbertson, the performances blaze with confidence and direction.

And the telltale quiet spots — such as the pristine dovetailing in the Esmail or the songful lines in the Adolphe — showcase an ensemble with exceptional finesse and a thoroughgoing understanding of this engaging fare.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

The British Isles have a rich tradition of anonymously written traditional songs, as well as songs written in imitation of, or perhaps homage to, those authentic ones. One of the most beloved of this latter group is “The Last Rose of Summer,” by the remarkable early 19th-century Irish poet Thomas Moore.

The British Isles have a rich tradition of anonymously written traditional songs, as well as songs written in imitation of, or perhaps homage to, those authentic ones. One of the most beloved of this latter group is “The Last Rose of Summer,” by the remarkable early 19th-century Irish poet Thomas Moore.

Many of these folk and folk-like songs have found their way to the recital stage, thanks to piano arrangements made by a wide range of musicians, from anonymous hardworking freelancers to such major composers as Benjamin Britten. (Aaron Copland did something analogous, and superbly, in his two books of Old American Songs, indelibly recorded by the late William Warfield.)

An intriguing CD has been released on the Somm label (SOMMCD 0668) bringing together no fewer than 27 such songs, ranging from the touching to the silly and sung by a remarkable variety of artists, including such renowned figures as Janis Kelly (soprano), Nicky Spence (tenor), and Kevin Whately, the television actor best known for his performances on the long-lived miniseries Inspector Morse and its spinoff, Lewis.

Listeners will be delighted to hear some songs they know by heart or at least by name (“The Foggy, Foggy Dew”) and equally by less familiar items, each of them sung here with what seem like more or less accurate regional accents (or, in a few songs, with words in Welsh — fortunately, translated in the helpful booklet).

One song, an affectionate parody of the whole English folksong genre by the comic actor and author Spike Milligan, is put across with a straight face and elegant grace by Elaine Delmar, who is apparently well known in Britain for cabaret performances (and also for featuring in Ken Russell’s 1974 film Mahler).

The performances gain much richness (to this resolutely American ear) if one follows closely the words in the booklet. It must be said that one song, “Blow the Wind Southerly,” though rendered well enough by mezzo Yvonne Howard, still falls short of the vocally rock-solid recording made by the great Kathleen Ferrier in 1956.

Some of the Britten accompaniments are straightforward, with witty details. Others risk overwhelming the vocal part with busy figuration and dissonant commentary. But they all raise interesting questions about what folk songs might mean for us today, nursed as most of us have been by a highly professionalized and commercialized musical and literary culture.

And how does Kevin Whately stack up against these highly trained professional singers? Quite well, I’d say. He puts his two songs across with spirit, like an experienced light tenor in a comic operetta. I notice in his bio that he busked in the London Underground to pay his way through the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. He has appeared on TV as Herbie opposite Imelda Staunton in the classic Broadway musical Gypsy (with songs by Stephen Sondheim and Jule Styne) and has narrated and sung in Bernstein’s remarkable, genre-busting Candide. I hope he’ll keep at it — he’s got flair to spare!

— Ralph P. Locke

Jazz

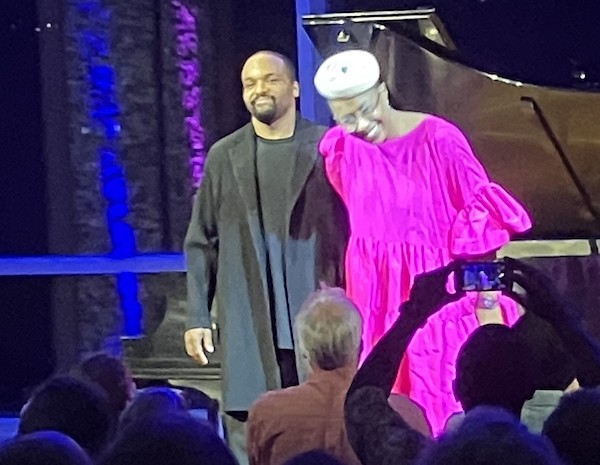

Cécile McLorin Salvant and Sullivan Fortner performing at the Shalin Liu Performance Center in Rockport on September 7. Photo: Steve Provizer

The last time I saw Cécile McLorin Salvant, she brought a full band. This time, just a piano player. With no bass and drums to maintain a groove, some listeners might have felt a loss of propulsion, but I welcomed the flexibility and fluidity it brought to the time. Phrases and chord changes were stretched out or truncated to fit the moment. A duo also encourages transparency: listeners can focus more closely on what one musician is doing and how the other is responding. And those pleasures were plentiful in this concert as vocalist Savant and pianist Sullivan Fortner listened as closely to each other as the audience members did to them.

There was a relaxed living room vibe to the concert. Salvant made it clear there was no prearranged set list. After each song, a brief conversation between her and Fortner led to the next tune. The first song, Bob Dorough’s “Devil May Care,” was the only one in the evening that could be strictly labeled a “jazz” tune — nothing here by Waller, Ellington, Shorter, Monk. “If I Should Lose You,” the other tune that one might call a “standard,” was beautifully done as a slow ballad.

Broadway and film music was well represented. The singer always makes a strong connection with her listeners, but this repertoire gave her the chance to generate an even stronger stage presence. Salvant skilfully explored the dramatic potential in “Ten Minutes Ago” and “Stepsister’s Lament” from Cinderella and “Climb Ev’ry Mountain,” from The Sound of Music. The duo also performed Salvant’s original “Splendor,” but this song, too, would not be out of place in a musical. The pair followed these up with “Sam Jones Blues,” which made for a nice contrast. Salvant alluded to the original Bessie Smith version but made it her own.

The duo then performed three strong compositions by singers they esteem: “Mista” by Diane Reeves, “No Love Dying” by Gregory Porter, and “Circling” by Gretchen Parlato. The encore was “Together (Wherever We Go),” from Gypsy.

As I noted in my review of the pair’s recording The Window, Savant is a performer of power, flexibility, control, and insight. The same can be said of Fortner, who also contributes a flair for the unexpected. One simply doesn’t know how he will approach his accompaniment and solos. But inspiration seems to be ever present. He is the perfect choice to partner with a singer who brings an exploratory edge to everything she does.

— Steve Provizer

Drummer Joe LaBarbera in action. Photo: courtesy of the artist

World Travelers (Sam First Records) was recorded by drummer Joe LaBarbera and his quintet live on March 4 and 5, 2022, in the Los Angeles club with the interesting name Sam First. LaBarbera is, I believe, best known as the sensitive, instantly responsive drummer in Bill Evans’s last trio. He’s the drummer on the six-disc collection, recorded in June 1980, and released as Bill Evans: Turn Out the Stars. On songs like “If You Could See Me Now,” LaBarbera doesn’t seem merely to follow Evans’s shifts in meter and tempo, but to predict them. Some of us saw him in 1978 at Sandy’s Jazz Revival with Bob Brookmeyer: the sessions ended up on a Gryphon LP. LaBarbera was subtle, but he could also be strong: early in his career, in 1972, he was the drummer on Woody Herman’s The Raven Speaks. He sounded right, both on the rollicking “Better Git It In Your Soul” with Herman and on Evans’s “My Foolish Heart”. Towards the beginning of his career, he worked with Chuck Mangione and traveled with John Scofield. He also recorded with Rosemary Clooney and repeatedly with Tony Bennett.

LaBarbera has led a half dozen recording sessions, often with the pianist on World Travelers, Bill Cunliffe. There are five pieces on the LP version: the download has additional numbers. I am pleased with the LP, for the clarity and warmth of its sound. Cunliffe introduces the first number, his “Blue Notes,” over the active drumming of the leader. The pleasing, bluesy tune is stated by tenor saxophonist Bob Sheppard and trumpeter Clay Jenkins. (The last member of the quintet is bassist Jonathan Richards.)

The LP ends with a lesser known piece by John Coltrane: his “Grand Central,” first recorded on Cannonball Adderley in Chicago, with Coltrane as a sideman. It starts with a resonant introduction by the drummer, who fills every pause in Clay Jenkins’s solo with accents on his tom toms. It is remarkable how much of the energy of the performance derives from the drums. LaBarbera thrives on Joe Lovano’s rhythmically kinky “Landmarks Along the Way” as well. Apologies to the drummer, but for me the highlight of the album is Duke Pearson’s tender ballad You Know I Care. (You should seek out the original on Pearson’s Honey Bun.) Bob Sheppard sounds like the ballad-playing Coltrane on his restrained statement of the theme. Led by a 75-year-old drummer, World Travelers is a session by consummate veterans who still have a thing or two to teach us.

— Michael Ullman

Here’s an odd album that keeps its secrets. The band’s name appears nowhere on the spare sleeve. It’s not even clear from the promotional materials if the band’s name is Elsa Nilsson’s Band of Pulses, Band of Pulses, or just Pulses. The cover art just has Pulses twice (once upside down) with a crude drawing that has little to do with the music. There are no track listings or composer credits. The recording was released on Ears & Eyes Records.

Here’s an odd album that keeps its secrets. The band’s name appears nowhere on the spare sleeve. It’s not even clear from the promotional materials if the band’s name is Elsa Nilsson’s Band of Pulses, Band of Pulses, or just Pulses. The cover art just has Pulses twice (once upside down) with a crude drawing that has little to do with the music. There are no track listings or composer credits. The recording was released on Ears & Eyes Records.

The music inside the cryptic sleeve has no problem communicating. Sweden-born Elsa Nilsson is an adventurous flautist who plays with energy and conviction. Her responsive quartet takes on an unusual project: a suite of mostly improvised music set to the voice of poet Maya Angelou reading “On the Pulse of Morning,” written for Bill Clinton’s 1993 inauguration. (Was the poem chosen because it has the word “Pulses” in the title? Or was the band named after the poem? Another mystery.)

It works to mixed effect. The music has shifting textures and rhythms, paralleling the range of the moods and registers of the poem. There are free passages, fast flurries, angry electronic outbursts, probing excursions, and tranquil meditations. Angelou’s reading is used in varying lengths across the album, sometimes with just a line or two, and sometimes in longer passages. At its best, the poetry sections launch the band into new musical directions with renewed energy. At its worst, the band scurries about with little or no connection to the poem’s content. At one point Angelou says “Lift up your hearts/Each new hour holds new chances/For new beginnings” while Nilsson’s switches on her FX pedals and makes her flute sound like a furious electric guitar and a sour distorted trombone.

What I find most interesting are the composed passages where the band plays in unison with the pitches, rises, falls, and intonations of Angelou’s speech. I wouldn’t have expected this, but it sounds like something Ornette Coleman would have played. Free of keys, harmonies, and conventional jazz phrasing, the musicians and the poet become one, and the melodies sound liberated and honest.

The album is a mixed bag, but it’s original, heartfelt, reaching, and it sure isn’t the same old thing. It follows Angelou’s advice: “The horizon leans forward/ Offering you space to place new steps of change.”

— Allen Michie

Hip-Hop

Cover art for We Buy Diabetic Test Strips

We Buy Diabetic Test Strips, the sixth album by billy woods and ELUCID’s group Armand Hammer, is hip-hop that hasn’t a boastful bone in its body. The music is abrasive enough to make for uncomfortable listening, but it is also fragile. There’s little of the swagger of noise rap. Samples are dizzyingly integrated with acoustic instruments, to the point that former Sons of Kemet leader Shabaka Hutchings’s flute is barely distinguishable from surrounding electronic textures.

The album’s fragments of noise and cavernous delay owe much to the influence of free jazz and dub reggae. (Cavalier’s feature on “I Keep a Mirror in My Pocket” welcomes a touch of dancehall.) Armand Hammer’s music is full of unexpected sounds. A fuzzed-out synthesizer erupts throughout “I Keep a Mirror in My Pocket,” and it is never less than startling. Sudden glitches function like drums on the otherwise near-empty “Don’t Lose Your Job.” Producer DJ Haram turns up in the “Trauma Mic” video slamming a pipe on some scrap metal (as heard on the song), while walking through a junkyard. Vocals are pushed under in the mix rather than serving as the focus of the music. Both appearances by vocalist Junglepussy are barely audible. For the first time, left woods’ Backwoodz Studioz label to sign to a larger record company, but the album makes no attempt to make their music more accessible.

Words are crucially important to Armand Hammer. Will anyone top what must be the song title of the year: “Woke Up and Asked Siri How I’m Gonna Die.” But that fascination with language means listeners must work to understand what the group is trying to put across. Double and triple meanings abound. For example, one line alludes both to woods’s own struggles and Kanye West’s descent into mental illness via a reference to West’s vanity label, G.O.O.D. Music. Zingers leap out of the mix, like “Henry Kissinger, my album’s only feature.” But, given the pileup of wordplay and puns, paying attention to the lyrics of an entire song can be a challenge.

We Buy Diabetic Test Strips supplies a soundtrack for living in an absurdly unsettling world. The production sounds either hollowed out (“The Flexible Unreality of Time & Memory”) or twitchy (“The Gods Must Be Crazy.”) The tracks buzz by as if you are half hearing them from passing cars; the music is almost drowned out by the noise of outdated phone lines and computerized voices. ELUCID and woods rap with a weary, disgusted tone whose frustration often boils over into sarcasm. That said, a spirit of community, with the contributions of long-term collaborators such as JPEGMAFIA, Fielded, and Curly Castro, presides. No solutions are offered. The thrust of the album is diagnostic: it reflects the psychic damage of living with racism and income inequality.

— Steve Erickson

Television

Craig Roberts and Lois Chimimba in Still Up. Photo: courtesy of Apple TV+

I love a good rom-com. It’s the genre that brought us feel-good classics like When Harry Met Sally, My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Amelie… the list is extensive. Unfortunately, for every great rom-com, there are 10 bad ones. Or worse yet, mediocre ones. Still Up, Apple TV+’s latest entry in the genre, falls into the “meh” category. Set in London, the series offers what might have been an entertaining twist on the usual: its protagonists are insomniacs whose interactions take place over the phone/FaceTime. The idea of a romance between people who can’t get enough sleep is intriguing. But Still Up quickly runs out of quirk.

Lisa (Antonia Thomas) and Danny (Craig Roberts) are undeniably charming. Their conversations generally evaluate the sleep recommendations that people give them (“Wear a hat full of lavender” is a standout). They also chatter about setting up Danny’s dating account and, among more pressing concerns, figuring out how he can hide from his neighbor, while he is holding a party for his cats, and still have a pizza delivered. As for work, Danny is an agoraphobe who was a music journalist and now just writes bland listicles. Lisa has a young daughter and a boyfriend, Veggie (Blake Harrison), who is reliable but comes off as extraordinarily boring. His best story is how his friend mixed three different types of Coke from the fountain machine. The pilot episode had all of Still Up‘s best gags, including the aforementioned cat party and Lisa trying to hide from a judgmental parent at the pharmacy.

Thomas and Roberts have some chemistry, but we are constantly told that they do rather than shown it. At the end of the opening episode, Lisa realizes she forgot to delete her old dating profile and learns she has been matched with Danny. This contrivance feels lazy — why tell us they belong together rather than show us? Why not reveal more of Danny’s and Lisa’s backstories in the beginning? Or hint as to why they aren’t together in the first place? As the installments of Still Up shuffle slowly along, their dependence on the comedic slow burn becomes a little too successful — the proceedings are as slow as a lullaby. This is a show about insomniacs that might help real life sufferers go to sleep.

— Sarah Osman

Visual Art

Arnold Böcklin, Shield with the Head of the Medusa, conceived in 1885 and modeled around 1887. Photo: Wadsworth Atheneum

A multicultural exhibition organized for the Halloween season, the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art’s Between Life and Death: Art and the Afterlife (through December 3) is an interesting idea in search of a group of objects, or perhaps a group of provocative objects in search of a unifying theme.

From the title, you might expect to find a selection of Doré’s Dante illustrations, a painting of the Resurrection, or perhaps an image of Pure Land Buddhism’s Amida Heaven, into which the faithful are reborn as lotus blossoms. Instead, you are introduced to a Big Subject: “What separates life from death?” intones the introductory panel. “Is death an end or only a beginning? How do we cope with the inevitability of dying? Today we spend much of our lives avoiding these questions.”

There is a sentimental Victorian marble memorial to two deceased sons; Francisco de Zurbaran’s beautifully composed and painted representation of the martyred Saint Serapian, commissioned by a monastery for a room where “deceased friars were laid out overnight before their burials”; a portrait of a dead nun; a creepy severed head of Medusa, rendered in painted plaster and papier mâché by the Swiss symbolist Arnold Bochlin, which changes its expression from terror to horror depending on the lighting; a life mask of Keats; and a collection of decorated plaster skulls related to the Dia de los Muertos, or the Mexican Day of the Dead.

Perhaps the most interesting exploration returns to the exhibition’s opening themes, inviting visitors to “write your own reflections on life, death, and grief” in a guest book. These range from bromides about living life while you can to touching remembrances of departed loved ones, to a disturbing confession about missing one’s dead dogs more than a deceased father. A concluding note suggests leaving a physical remembrance at “a traditional ofrenda” designed by artist Carlos Hernandez Chavez, installed in the contemporary gallery from October 11.

— Peter Walsh

Tagged: "Pulses", "Shatter", "Still Up", "World Travelers", Allen Michie, Apple TV, Armand Hammer, Between Life and Death: Art and the Afterlife, Cécile McLorin Salvant, Cyrisse Jaffee, Elsa Nilsson, Folk Songs of the British Isles, Gary D. Schmidt, Joe LaBarbera, Kevin Whately, Michael Ullman, Peter Keough, Steve Provizer, Sullivan Fortner, The Labors of Hercules Beal, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, Verona Quartet