Television Review: “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” — The Virtues of Redemption

By Peter Keough

Less is more in Wes Anderson’s adaptation of Roald Dahl’s The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar.

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar. Directed by Wes Anderson. Based on the Roald Dahl short story. One of four Anderson shorts adapting Dahl stories available on Netflix.

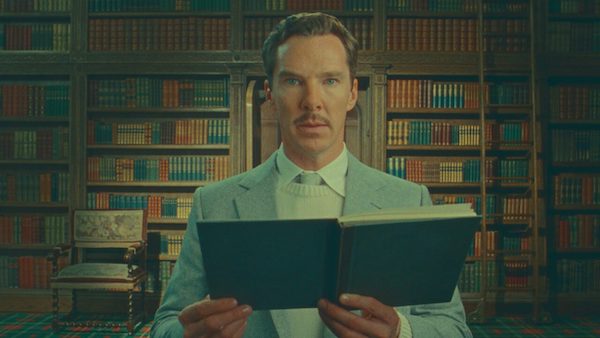

Benedict Cumberbatch stars in The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar on Netflix.

Even when it comes from ironists like Roald Dahl and Wes Anderson, any story whose title contains the words “Wonderful” and “Sugar” won’t offer much in the way of darkness. Unlike his dense, bittersweet parable of grief and loss Asteroid City, Anderson’s adaptation of Dahl’s short story “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” (on Netflix) celebrates, in its deadpan, dazzling way, the virtues of redemption, philanthropy, and positive thinking.

Played by a buttoned-up, tweedy Benedict Cumberbatch, Sugar is described by a buttoned-up, tweedy Roald Dahl (Ralph Fiennes) during the course of his opening set-up of the story as wealthy, selfish, greedy, and worthless. Men like him, Dahl explains, “are to be found drifting like seaweed…They are not particularly bad men. But they are not good men. They are of no real importance.”

Having been thus indifferently introduced, Sugar himself picks up the chronicle and relates how, during one period of indolence, he came across a pamphlet written many years before by a Doctor Chatterjee (Dev Patel) about a certain Imdad Khan (Ben Kingsley), an Indian yogi with a stage act in which he can see with his eyes closed. Recognizing the possibilities of cheating at games of chance with such a gift, Sugar studies the pamphlet’s detailed instructions about how Khan learned the trick from a fakir he caught levitating. A basic form of meditation, it involves removing all extraneous thoughts and images from one’s mind and focusing on one thing — at first a face, and then a candle.

Perhaps because he is the least deserving person to have such a gift, Sugar proves most adept at attaining it. After a few years of intensive study, the only protracted work he has ever done in his life, Sugar can read the back of a playing card within five seconds. He heads to a casino, sits at the blackjack table, and careful not to win too much and give the game away, he returns home with 30,000 pounds.

He feels — empty. Actually, his conversion into a less materialistic state of mind begins as soon as he enters the casino. He discovers that “for the first time in [his] life,” as he relates directly to the camera, “he looked with distaste on a room full of rich people.” And soon (spoiler!), disgusted with money and with a sudden upsurge of empathy, Henry puts together a plan to utilize his skill and resources for the benefit of others.

Though lighter in tone and themes, Henry Sugar rivals Asteroid City in the reflexive ingenuity of its form and style. The film is as much about storytellers and the art of storytelling as it is about the narrative itself. A matryoshka-like series of narrators — beginning with Dahl himself — spin out the tale, which is enacted with sliding cut-out scenery and insouciant props that are briskly placed and removed, sometimes with the stolid stagehands entering the frame. As each new character enters, they take up the tale with the same earnest, affectless, droll demeanor (there are no female characters, take that for what you will). It looks like a sleek stage production or an ingeniously designed pop-up book. Anderson, as is his wont, does not try to hide the artifice, but revels in it. The fakery is the point of what comes off as a pleasant sleight of cinematic handiwork.

Or maybe deception is beside the point. Henry Sugar draws on some of Asteroid City‘s color template (reminiscent of orange Tang and Tropical Fruit LifeSavers), but it has none of that film’s brooding monochromatic cinematography. The only lasting darkness is a mention of the “little black area of burning nothingness” at the center of the candle flame where Henry loses himself and gains his soul.

While a lesser artist might try to depict that void with CGI or other means, Anderson wisely demurs. Nonetheless, it shines forth as the vacant, vital heart of this deceptively slight bagatelle.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Tagged: Benedict Cumberbatch, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar