Film Interview: At the IFFB — “Road to Ruane” Pays Tribute to Boston’s Rock ‘n’ Roll Benefactor Billy Ruane

By Noah Schaffer

“Billy Ruane built a legacy, and 14 years after his death you can still feel his presence in local clubs. He fermented a scene that still lives on today.”

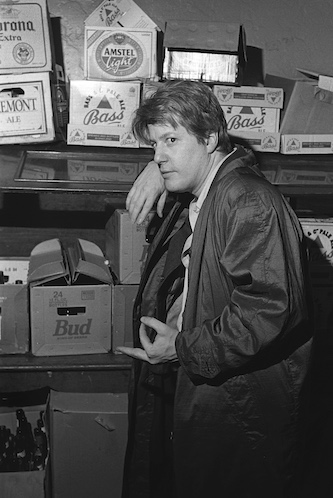

Billy Ruane pointing at a box of Budweiser. Photo: Eric Antoniou

One of the most anticipated films about Boston music is finally premiering this week, and it’s not about a musician. Billy Ruane was a scenester, patron, and genius curator whose role in creating the Central Square rock scene cannot be overstated. Musicians remember him for his unwavering enthusiasm and generosity, while few audience members could forget his spasmic dance moves and drunken band introductions. Ruane’s wildly eclectic series at venues like the Middle East and Green Street Grill might feature an up-and-comer Elliot Smith one night and a jazz master like Sam Rivers or Noah Howard the next.

Ruane, who battled bipolar disease, lived a life of ecstatic highs and crushing lows. The moving and lovingly crafted film The Road to Ruane tells his story. The “centerpiece documentary spotlight film” at the Independent Film Festival Boston, the film is receiving its world premiere this Saturday night at the Somerville Theatre.

Co-director Scott Evans talked to the Arts Fuse about The Road to Ruane’s long road to the screen. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Arts Fuse: Michael Gill started this film in 2010, the year that Billy Ruane died of a heart attack right before his 53rd birthday. Even by music documentary standards that’s an exceptionally long time to finish a movie. Why did it take so long?

Scott Evans: Mike had talked to Billy about making a documentary when Billy was alive. When Mike went to Billy’s memorial at the Middle East, [co-owner] Joseph Sater said ‘You have to film everything,’ and Mike filmed the memorial, which was really the start. But Mike had unknowingly been working on it before that, because he had been filming shows for Billy for years. He was slowly funding it himself, so he’d catch an artist perform somewhere, and get an interview with them, and that person would say ‘talk to this person’ and it kept spiraling out until there was a web of over 80 interviews. When it got to the point where Mike was unable to finish it, which we get into in the movie, I started to take over the project. We added the animation and also the original music. Mike and myself were really great friends and collaborators.

AF: I remember that any time I went to a Billy Ruane–promoted show, including some great jazz shows by underrated masters like Noah Howard and Sam Rivers, there was always that camera rolling, which wasn’t all that common back in the ’90s. Between that footage and the interviews, how did you edit down such an immense amount of footage into a coherent narrative?

The Road to Ruane co-director Scott Evans. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Evans: I think there were 90 interviews, and there are thousands of shows that were recorded. Greg Dalton-Kay has been meticulously archiving those tapes for years and posting them on YouTube. So that’s another reason the movie took so long.

AF: Many people in the Boston music world knew Billy extremely well, but I imagine you also want this documentary to mean something to viewers who’ve never even heard of Billy. How did you approach satisfying both of those audiences?

Evans: There’s an inherent interest in the Boston indie rock music scene of the ’90s. But what begins as a brief introduction to music history becomes a man vs. himself character study. Mike Gill liked documentaries that go beyond the subject matter and tap into the human condition. As Pat McGrath [owner of the Looney Tunes record store, longtime Ruane confidant, and a central figure in the film] notes, Billy was so extreme that looking at his life turns into an examination of the extreme in the the human condition. Billy’s story deals with life, success, failure, mortality, love, and loss.… This will be the first Boston screening, but not the last. We’re looking to do a [Boston theatrical run] later this year and we’ll be seeking distribution.

AF: Was it a challenge that there was so much footage of Billy in one context, on stage doing his crazy band introductions or wild dancing, but so little footage of the other sides of his life?

Evans: Mike organized things extremely well. It was essential to do that kind of groundwork — watching all of the footage and organizing it into themes — before you could construct the narrative. We also had this amazing vérité footage that Jesse Peretz of The Lemonheads had shot for a Harvard project. Billy loved to make phone calls, and people had saved his voicemails. So we did have a variety of the elements in his life to choose from. Billy was Billy every day, and that’s why people loved to be around him.

AF: When I first encountered Billy, people would sort of mention in passing that he came from money. That, it turns out, was a real understatement. I always wondered what his family thought of him — if he was a black sheep. What did you discover?

Evans: There was a lot of love there. He was at some level a black sheep. Billy was diagnosed with a mental illness starting in the ’70s, at a time people really didn’t openly talk about it. And there weren’t many treatment options — you had lithium and shock therapy going on. [Later on] Billy would take medication and find he was numbed and didn’t have the creative energy he thrived on. The scene or curation wouldn’t have come about without Billy’s manic side; that’s where he felt his genius, that’s what gave him the energy he needed to promote these shows and make his mixtapes and be so giving. His family certainly loved him, but, besides the mental illness, there were other big traumas in his life. Learning about them will help people understand his pain.

Billy Ruane on stage at the On Your Neez Show. Photo: Wayne Viens

AF: And speaking of money, the tricky relationship between a patron and an artist is a very old story. How do you think Billy’s access to money — which he seemingly had no interest in, except to divert it to struggling musicians — impacted his relationship with the artists who played at his shows and hung out with him? Clearly, everyone in this film had a very sincere love for Billy. But do you think anyone exploited him?

Evans: Pat McGrath suggests that maybe towards the end there were people who were taking advantage of Billy because he was so giving. But it wouldn’t matter either way to him. Money was something that he could provide if someone was in need. Billy was never in want, except for a great love in his life. Some people were sad that he lived his life alone. But Billy was out every night. He loved creating an art and music scene that felt like a family. He’d walk into a place and buy everyone drinks and make sure they got home with a cab voucher. He was a wonderful guy for a lot of people. But there was another side to him, where he could flip on a dime and yell and scream. But he never held grudges — it was just the imbalances going on in his brain. He built a legacy, and 14 years after his death you can still feel his presence in local clubs. He fermented a scene that still lives on today.

Noah Schaffer is a Boston-based journalist and the co-author of gospel singer Spencer Taylor Jr.’s autobiography A General Becomes a Legend. He also is a correspondent for the Boston Globe, and spent two decades as a reporter and editor at Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly and Worcester Magazine. He has produced a trio of documentaries for public radio’s Afropop Worldwide, and was the researcher and liner notes writer for Take Us Home – Boston Roots Reggae from 1979 to 1988. He is a two-time Boston Music Award nominee in the music journalism category. In 2022 he co-produced and wrote the liner notes for The Skippy White Story: Boston Soul 1961-1967, which was named one of the top boxed sets of the year by the New York Times.

Tagged: "The Road to Ruane", Billy Ruane, IFFB 2024, Independent Film Festival Boston, Michael Gill