Jazz CD Review: Cécile McLorin Salvant’s “The Window” — A Very Beautiful View

The Window presents an inspired pairing — between singer Cécile McLorin Salvant and pianist-organist Sullivan Fortner.

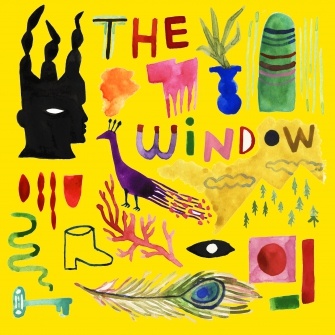

Cécile McLorin Salvant, The Window, (Mack Avenue)

Cécile McLorin Salvant – this singer demonstrates a rare power, flexibility, control, and insight. Photo: Mark Fitton.

By Steve Provizer

I had heard scattered tracks and been impressed, but this was the first time I had gone more deeply into Cécile McLorin Salvant’s music. And now I understand what all the fuss is about. In The Window, her fourth album, Salvant demonstrates a rare vocal power, flexibility, control, and insight. She and fellow explorer Sullivan Fortner, a pianist-organist from New Orleans, are compelling when they run down tunes and make few changes in their characteristic approaches. But when they decide to deeply explore the emotional boundaries of a song, they make dazzling music.

Stevie Wonder’s “Visions” opens with a slightly impressionistic piano introduction. Wonder performs the original version of his composition in a thoughtful vein; this is an even slower, more expressive delivery of the melody. Wonder’s instrumental backing shimmers and here, with just acoustic piano, it is, of course, simpler. However, Fortner’s harmonic approach still brings out some of the original’s shimmering quality. Lyrically, a story is being told, but it is not easily teased out. Salvant manages to guide us there successfully. The piano solo sometimes adds another layer of harmonic and melodic complication, and sometimes leaves it as is. As in Wonder’s version, Slavant’s entrance after the instrumental interlude is much more forceful, though she brings the energy way down, supplying a tenuousness that is supported by a harmonically ambiguous piano. The rendition is close to the initial recording, but this version expands the musical palette and, for me, evokes a wider emotional range.

“One Step (Ahead)” was notably recorded by Aretha Franklin in 1967. Everything Aretha touches turns to soul, at least to me, but this was a pretty pop-ish tune for her, with a fairly elaborate backing of chorus and strings. Salvant’s version is a sprightlier jazz waltz. The addition of organ suggests the funkier quality of the original. Savant delivers the tune more intimately than Aretha, bringing in more variation in emphasis and dynamics. The effect is that Aretha seems to be singing to the masses, while Cecile is singing to an audience of one.

A capella voice starts off the Richard Rodgers standard “The Sweetest Sounds.” Salvant is then joined by Fortner in a slow first chorus. The track’s piano solo combines interesting intimations of “outside” techniques with a little stride and some Bill Evans colorations. Fortner breaks up the time in a very singular way: there’s a restlessness to his playing that draws on an amalgamation of approaches, yet his style remains coherent rather than disjointed. After the initial chorus and the piano solo, voice, somewhat surprisingly, never comes back in.

“Ever Since The One I Love’s Been Gone” was notably recorded by baritone Buddy Johnson and his Orchestra in 1950. There’s a Lady Day quality to the tone of this tune, especially at the beginning. Salvant’s voice, as we hear here, has a wider range than Holiday’s and makes fuller use of dynamics. She pushes hard, but manages to sound like she’s not trying too hard — a result of inhabiting the lyric of the song. There’s even a bit of Mal Waldron (Holiday’s sometime accompanist) in the piano solo, although there is a wider tonal palette and fuller use of the keyboard than one gets from Waldron. After the piano solo, Salvant goes quickly from full near-operatic voice to a whisper. The resources that vocalist and pianist bring mesh nicely here.

“A Clef,” sung in convincingly accented French, is wistful and airy. This nicely handled performance touches on ruefulmess, but has a little too much animation to be overly melancholic.

“Obsession” has been sung as an up-tempo Brazilian tune (Sarah Vaughan) or as an exercise in upbeat show-music (Dianne Reeves). This version is a big departure. The tempo is not slow, but it is rubato. The feeling expressed is of someone unsure whether to stop or to go ahead. There is a refrain in the song that is usually taken as kind of a dramatic payoff: “Some place there must be a place where two heartbeats can touch.” But in this version there is an almost off-handed quality to Salvant’s delivery; a feeling not so much of either longing or anger as of “show me that you can care.” It’s actually a fairly daring approach — and it works.

In French, “Jai le Cafard” means, more or less, I’ve got the blues. It’s a ’20’s song and Fortner’s pipe organ accompaniment provides an appropriately period feeling. Salvant sings the tune with a slightly less dramatic, more playful quality than Fréhel or Edith Piaf, switching convincingly, as the lyrics dictate, between wistfulness, dyspepsia, displeasure, and world-weariness.

Fortner foreshadows the vocal entrance in “Somewhere” by quoting several West Side Story tunes in his intro. Initially, Salvant’s approach is a little too cloying for me, as if she couldn’t really convince herself that there really IS “a time for us.” As she moves through the song, though, she finds her way into its emotional core. After the first chorus, the piano goes to a series of sixteenth notes that seems to foreshadow disaster. Fortner builds a large orchestral sound, but continues with those sixteenth notes almost all the way through the solo. Voice re-enters a capella, building up dynamically from piano to forte and then closing on a more enigmatic note.

For me, “The Gentleman is a Dope,” by Rodgers and Hammerstein, found its best interpreter in Blossom Dearie. Salvant’s version is close to hers in tempo and attitude. I hear her toying with the Dearie connection, moving from a more forceful approach and touching on Dearie’s lighter, more girl-like voice. The piano playing, though, is a distant cry from Dearie’s, who was a good musician but didn’t have anything like the resources Fortner has.

“Trouble is a Man” is a much-recorded torch song, written by Alec Wilder. The approach here is almost lieder-like. Fortner’s piano accompaniment moves between a common jazz vocal approach and a style that is not far from what one hears in Debussy chansons or Schubert lieder. The strategy suits this song wonderfully; when he returns to a standard jazz background, the energy dips. This is a challenging song for a vocalist because it can ease so easily into the bathetic. Happily, Savant varies her approach, with dramatic stops, starts, and declamations. I would take her rendition of this over that of Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughn — which is saying something.

“Were Thine (That Special Face),” from Kiss Me Kate, is written for a male voice. Salvant does the verse, which I think is pretty rare, but Cole Porter lyrics are usually worth hearing. They take the implied tango rhythm and bring it out fully.

In the performance of the Coleman-Leigh standard “I’ve Got Your Number,” it’s interesting to just follow the piano accompaniment. Piano sets up a continuo feeling and adds in some bass line as the vocal comes in, then moves to a relaxed stride. Then Fortner chooses a more varied rhythmic background. So, while the vocal is straightforward in the first chorus, the varying accompaniment adds a sense of movement and variety. I grew to expect interesting twists and turns in the piano solos and this one is no exception. When the vocal returns, Salvant modulates her voice in half a dozen different ways to change-up the feeling. An intriguing rendition.

“Everything I’ve Got Belongs to You” is another tune associated with Blossom Dearie. They take it a bit faster here. In fact, they only do one chorus and they’re out in a quick 1’10”.

“Peacocks,” (more usually called “The Peacocks”), was written by pianist Jimmy Rowles, with lyrics by Norma Winstone. The piano arpeggiations, the large dynamic range of the voice, the whole tone and dissonant attitude recalls the lieder-sque approach the duo took on “Trouble is A Man.” This is the only track with another instrument, Chilean tenor and soprano sax player Melissa Aldana, who gets the vibe and fits in perfectly. Salvant deeply explores and pushes the melody; the piano is light and deft. An improvised sax-piano interlude follows, flirting with a dissonant and whole-tone feeling, but never crossing completely over. Piano leads back into the vocal, with quartertones purposely traded between voice and sax. They move to a section that elongates the melody and sets the three musicians in almost furtive juxtaposition. Then, sax and piano close with tight trills and arpeggios. Boldly and beautifully done.

The Window showcases an inspired pairing. Both performers have protean skills and can draw on a wide range of styles. Even when the pair approach songs in a straightforward fashion, the juxtaposition of Salvant’s voice and Fortner’s piano makes for engrossing listening. However, when they commit to pushing beyond the usual musical-emotional boundaries of a song, they create distinctive, exciting music.

Steve Provizer is a jazz brass player and vocalist, leads a band called Skylight and plays with the Leap of Faith Orchestra. He has a radio show Thursdays at 5 p.m. on WZBC, 90.3 FM and has been blogging about jazz since 2010.