Book Review: “Heavy Duty: Days and Nights in Judas Priest”

K.K. Downing does not trash Judas Priest or its legacy, but he gives, from his perspective, an honest and believable assessment of the group and his role in it.

Heavy Duty: Days and Nights in Judas Priest by K.K. Downing with Mark Eglinton. Da Capo, 288 pages, $14.99.

By Scott McLennan

For all of his claims about being passive to a fault, guitarist K.K. Downing has beaten others to the punch in terms of writing a book about Judas Priest as the storied heavy metal band heads toward its 50th anniversary in 2019.

Heavy Duty: Days and Nights in Judas Priest isn’t so much a book about Judas Priest as it is one about being a member of Judas Priest. That makes Downing’s story particularly intriguing because it does not follow the contours of what has become the typical rock ’n’ roll fantasy. Music gave Downing the means to escape the unhappiness of his youth, but it did not provide a guaranteed pass to a happy adulthood. As he writes on the outset of his tale:

When I first started thinking about writing about my life in and out of Judas Priest, as I tried to identify and prioritize all the things I wanted to say and thoughts I wanted to get across, the feeling that I just could not shake was the idea that a person’s upbringing shapes everything that happens later. Everything.

And his upbringing in England was bleak: abusive father; unsteady living arrangements; not much money in the family. Those issues as well as Downing’s small physical stature meant that he would be a social outcast with few friends. Add to those problems the fact that he had no real interests, in or outside of school. Downing’s future seemed anything but sunny.

Without stating so outright, Downing comes off as being a special sort of misfit, the kind of person who could only have found his place in the community of heavy metal fans. Of course, during Downing’s years as a young malcontent heavy metal did not really exist.

The musician goes into how he unintentionally set himself up as an architect of the genre. His preference for the Rolling Stones, Pretty Things, and Troggs over the Beatles and Elvis Presley (“Those were my sister’s favorites”) reflects how he favored music with a darker tone and more sinister attitude. He liked the bands that did not conform to a clean, wholesome look.

Downing was also a huge fan of Jimi Hendrix. Seeing Hendrix perform in England three times—and actually meeting the guitar legend briefly at a festival just weeks before Hendrix died—inspired Downing not only to hunker down and learn how to play guitar, but to play the instrument in a way that expressed his feelings in ways that the blues-based rock of the time simply was not capable of.

By the early ’70s, Downing was in the hunt to be in a band. He and bassist Ian Hill eventually found guitarist Glen Tipton and singer Rob Halford, which completed a lineup that was ready to write, record, and perform at a level necessary for Judas Priest to go from local attraction to bona fide rock stars.

Tipton and Downing brought fresh approach to hard rock by adopting Hendrix’s flash and colorful tones and using them to express more menacing and dark themes. In Halford, Judas Priest had — and still has — one of heavy metal’s defining voices.

Downing supplies plenty of stories and anecdotes about the songs and albums that solidified heavy metal as a distinct sub-genre of rock. And he charts Judas Priest’s progression from underground sensations to arena-packing stars.

Most amazing is how very un-rock ’n’ roll the job could be. Yes, the book references groupies and debauchery to the point that playing in Judas Priest looks like a very different job than the kind of construction and hotel work Downing did as a young man. But Downing’s descriptions of playing in the band come across as determinedly workmanlike. Whatever successes he and his mates accrued — artistically and financially — came about through a solid work ethic and effort (AC/DC and Status Quo, he tells us, were the ones with the gifts to make anything sound good).

Downing did not have the natural talent of Halford or the shrewd and domineering personality of Tipton. His early insecurities and introverted personality never fully left him — no matter how big and successful Judas Priest became.

Thus, much like going into the office, Downing spent his career in Judas Priest at odds with a co-worker (Tipton) he found difficult to get along with. He embraced a stance of non-confrontation to avoid conflict with the others. Hell, Downing even took up golf as a pastime.

Ironically, as much as Downing contributed to the success of Judas Priest in terms of the band’s sound and look, he now sees that his unwillingness to challenge others’ decisions not only brought him unhappiness, but also held back Judas Priest from moving into the highest echelons of rock stardom. Its sobering to read that Priest’s best-selling album Screaming for Vengeance did not even come close to achieving the commercial success attained by other bands, such as Metallica, Def Leppard, and Priest’s rival Iron Maiden.

“So the conclusion that I arrive at is that we massively underachieved in a financial and creative sense,” he confesses.

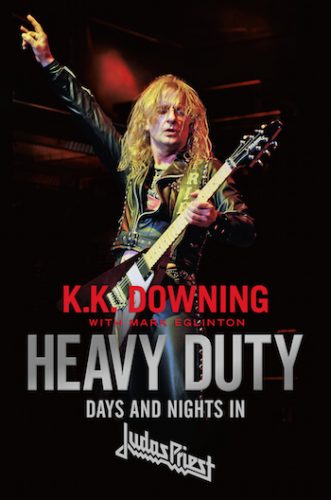

K.K. Downing of Judas Priest. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Downing does not trash Judas Priest or its legacy, but he gives, from his perspective, an honest and believable assessment of the group and his role in it.

Nice guy that he is, Downing does not spill the beans in any way that will embarrass someone. He even offers conciliatory remarks to Tipton and Iron Maiden. He does unload, however, on the people who sued Judas Priest in 1990, claiming the band’s music drove two young men to commit suicide. While respecting the victims of the tragedy, Downing draws parallels between his own dysfunctional family’s behaviors to those of the families suing the band. The passages suggest that Downing will fight back when he and the band are hit in a particularly tender spot.

Feeling that the band’s chemistry had deteriorated, Downing left Judas Priest in 2011. Judas Priest brought in a new guitarist and remains active (Tipton revealed earlier this year that he is battling Parkinson’s disease. He has stopped touring with the band and he has been replaced, though he has been contributing to writing and recording new Priest music).

Downing does not go into his post-Priest life, which involved trying to operate a golf course. And there are few details about the years when Judas Priest was inactive after Halford departed in 1992 and the band resurrected itself in 1996 with singer Tim Owens. Downing glosses over Owens’ tenure as a speed bump en route to a successful reunion with Halford in 2003.

He maintains some privacy around the least public aspects of his life, but Downing is refreshingly open about his disappointments and failings. Heavy Duty makes it clear that the man who helped pen the anthem “Metal Gods” is, in fact, quite human.

Scott McLennan covered music for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette from 1993 to 2008. He then contributed music reviews and features to The Boston Globe, The Providence Journal, The Portland Press Herald and WGBH, as well as to the Arts Fuse. He also operated the NE Metal blog to provide in-depth coverage of the region’s heavy metal scene.

Tagged: Da Capo, Heavy Duty: Days and Nights in Judas Priest, Judas Priest, K.K. Downing