Opera Album Review: A Splendiferous First Recording of an Opera by the Near-Legendary Composer Marin Marais

By Ralph P. Locke

Marin Marais, memorably enacted by Gérard Depardieu (and his son Guillaume) in the film Tous les matins du monde, proves a master of Baroque opera in this splendid recording.

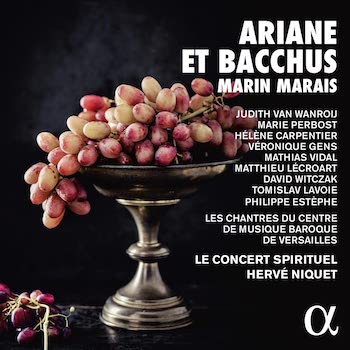

Marin Maris: Ariane et Bacchus.

Judith Van Wanroij, Véronique Gens, Mathias Vidal, Matthieu Lécroart, Tomislav Lavoie, and Philippe Estèphe, among others (and some take more than one role — see below).

Le Concert Spirituel, cond. Hervé Niquet.

Alpha 926 [2CDs] 126 minutes

Click to purchase or to hear any track.

Music lovers around the world know and love “the Bach Chaconne,” meaning the movement that ends his Partita for Solo Violin in D Minor. They want to hear it again and again: on modern or period violin, or arranged for piano by Brahms or Busoni, or with a chorus adding (unauthorized) phrases from Lutheran chorale tunes that fit the harmony at a given moment. But how many of these listeners know the glorious chaconnes that preceded that one movement by Bach and that are found in numerous serious operas (tragédies lyriques) by Lully and other French composers of the era we lump together as “the Baroque”?

Music lovers around the world know and love “the Bach Chaconne,” meaning the movement that ends his Partita for Solo Violin in D Minor. They want to hear it again and again: on modern or period violin, or arranged for piano by Brahms or Busoni, or with a chorus adding (unauthorized) phrases from Lutheran chorale tunes that fit the harmony at a given moment. But how many of these listeners know the glorious chaconnes that preceded that one movement by Bach and that are found in numerous serious operas (tragédies lyriques) by Lully and other French composers of the era we lump together as “the Baroque”?

Well, there’s a particularly glorious chaconne in the middle of Act 2 of Ariane et Bacchus (1696), one of four surviving operas by Marin Marais (1656-1728), a composer better known for his instrumental works, notably pieces for bass viola da gamba (“basse de viole”). Marais’s instrumental pieces became widely known through the 1991 film Tous les matins du monde, starring Gérard Depardieu and his son Guillaume as, respectively, the great master-musician Saint-Colombe and Marais in his younger years.

Ariane has now been recorded for the first time, and it’s a splendiferous affair.

The opera’s plot derives from Greek legends about Ariadne. Briefly, before the opera opens, she has saved Theseus from the Minotaur, and he has abandoned her on Naxos and run off with her sister Phaedra. In the course of the story, Ariadne and Bacchus (Dionysus) become infatuated with each other, and their love is blocked by other characters, including Juno, who is still angry that her husband Jupiter had an affair with Semele (resulting in the birth of Bacchus). Juno makes Ariadne believe that Bacchus is unfaithful to her. Adrastus, who has fallen in love with Ariadne, seeks revenge on Ariadne because she prefers Bacchus, but the forces of the Underworld refuse to help him. Ariadne, still feeling rejected, seeks to kill Bacchus, but, at the last moment, falls into despair and turns the knife on herself. Mercury intervenes, cures her of her madness, Jupiter and Juno (finally reconciled) consecrate the union of the couple, and Ariadne’s crown is borne to the heavens to become stars.

All of this largely enchanted action is supported by music that I found appropriately enchanting. The action proceeds mainly in short vocal solos and duets, often preceded and followed by instrumental ritornellos. But there are also numerous orchestral numbers (an overture, entr’actes, dances, and, in Act 4, music for the “entry of the demons”) and some choral numbers, especially in scenes of solemnity or communal rejoicing.

The instruments here are numerous and colorful. Four oboists and four bassoonists are listed, all doubling at some point on recorder! The booklet-essay explains that the recording follows the best musicological guidance in not using the continuo instruments during most of the purely instrumental passages. In an interview that I found online, Benoît Dratwicki, artistic director of the Versailles Center for Baroque Music, explains that this was proposed as long ago as 1981 by the scholar Graham Sadler and is now being put into practice in four opera recordings produced by the Versailles Center. The conductor of this recording, Hervé Niquet, describes the plan well in a five-minute video. I don’t know the evidence, but the result here is wondrous: the ear is refreshed when the continuo drops out and refreshed again when it returns.

Portrait of Marin Maris by André Bouys, 1704. Photo: Wiki Common

The singers are largely splendid. I have praised Judith Van Wanroij, Véronique Gens, Mathias Vidal, and Matthieu Lécroart on previous occasions, in wildly varying repertory (by such composers as Grétry, Félicien David, Gounod, and Saint-Saëns). Here they offer exemplary renderings, never allowing concern for the music to interfere with their attention to text or vice versa. Some of the low-voiced males are a little thin at the bottom end, but that’s not unusual these days in the opera world, generally (as noted opera critic Conrad L. Osborne has pointed out).

Various of the singers take more than one role, in part because there’s a long prologue, with entirely different roles than the rest of the opera. So you’ll want to follow the libretto, which is given in the booklet in French and good English. If you don’t follow the libretto, you might easily be misled when a singer keeps mentioning the name of a character: s/he is actually often speaking of her/himself. Juno, for one, loves to describe her feelings in the third person. The effect, in her case, strikes me as properly haughty. Fortunately, the various singers have distinctive enough voices and interpretive manners that I gradually learned to tell them apart without recourse to the libretto.

One of the wonderful things about French Baroque opera is that the musical numbers are constantly attractive, with a dance or march or pantomime scene always around the corner. And the phrase structure is often unpredictable, unlike the foursquare-ness of much music of the late 1700s and early 1800s. In short, you could, I suppose, listen to Marais’s opera without looking at the libretto at all (or even thinking about the rather episodic plot) and still have a fine time and enjoy many surprises.

Still, the experience is that much richer if you know what Junon or Adraste (to use their French names) is up to at a given moment.

Wow, there’s a whole ’nother side to Marais that most of us knew nothing about! Maybe a second movie could be made about Marais’s operatic career: the necessary wranglings with librettists, government officials, singers, and so on? Who might star in it today? (Depardieu is only a few years older than Marais was when he died, so….)

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Alpha, Ariane et Bacchus, Hervé Niquet, Judith Van Wanroij, Le Concert Spirituel, Marin Maris, Mathias Vidal, Matthieu Lécroart

Charming review, Ralph! What is the instrument that Marais is playing in the painting?