Opera Album Review: Two Surrealistically Delightful One-Acts

By Ralph P. Locke

Bohuslav Martinů, one of the greatest Czech-born composers, reveals a dark-comic sensibility in his rarely performed “Knife” and “Bridge” operas.

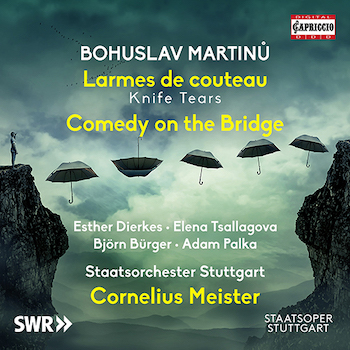

Bohuslav Martinů: Larmes de couteau and Comedy on the Bridge.

Esther Dierkes, Elena Psallagova, sopranos; Maria Riccarda Wesseling, Stine Marie Fischer, altos; Michael Smallwood, tenor; Björn Buerger, Adam Palka, baritone; Andrew Bogard, bass.

Stuttgart State Orchestra, cond. Cornelius Meister.

Capriccio C5477—65 minutes.

To hear the tracks or to purchase, click here.

For this review I got the chance to explore works by a composer who gets obscured by the vast scale of his output. Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959) was such an enormously prolific and diverse composer that we are hard-pressed to characterize his music in one breath, or even a few. Apart from the sheer volume of works he composed, his style shifted continually over the course of his lifetime, as he sought to assimilate and synthesize the sounds that he heard in each place he lived. Also impeding a concise characterization of his music is the way he would respond to the demands of each new work, giving careful consideration to the performers, medium, and audience for which he was composing.

For this review I got the chance to explore works by a composer who gets obscured by the vast scale of his output. Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959) was such an enormously prolific and diverse composer that we are hard-pressed to characterize his music in one breath, or even a few. Apart from the sheer volume of works he composed, his style shifted continually over the course of his lifetime, as he sought to assimilate and synthesize the sounds that he heard in each place he lived. Also impeding a concise characterization of his music is the way he would respond to the demands of each new work, giving careful consideration to the performers, medium, and audience for which he was composing.

Coming from a provincial Czech background but trained in Prague, he spent his crucial midlife years in Paris. He then fled Paris for New York, once his homeland and France were occupied by Nazi Germany. He was single-minded as a composer, often composing at his desk or in his mind — and some people described him as rather shy. (One biography posits that he was on the mild end of the autism spectrum.) He spent his last years shuttling between the US, Italy, and France (Nice, to be precise) and died in Switzerland.

Martinů composed in many different genres, including six symphonies, plus concertos and other works with orchestra. He is increasingly recognized for his operas, most notably The Greek Passion (I recommend a recording of it that was made in English) and Juliette or, in Czech, Julietta (three recordings; there’s also an orchestral suite from it).

This CD offers two comic one-act operas, each of which has been available in highly praised recordings done in Czech. I love the sound of Czech singers speaking and singing in their native language. The country seems to have a rich tradition for putting a text across with spirit and specificity, as I noted when comparing a new recording of Janáček’s The Cunning Little Vixen (with many Britons and Americans) to a much more engaging older recording made with singers who are native Czech-speakers.

Fortunately, here the singers — an international bunch — are performing in languages that they clearly understand (whereas Czech, for many or all, would likely have posed a serious impediment), and they put the text across well, while vocalizing very securely, if without that engagingly bright Czech edginess. The Stuttgart orchestra plays with spirit and high virtuosity under conductor Cornelius Meister.

Larmes de couteau, from 1928, was written to a French libretto. This seems to be the work’s first recording in the original language. I think the title engages in wordplay: a “lame de couteau” is the blade of a knife, yet in this work it is “laRmes” (teardrops) that are associated with a knife. The plot is an expressionist or surrealistic fairy tale (I’ll let theater historians debate those two adjectives), from the same dreamworld as several operas by Zemlinsky and Schreker. It was first performed in 1969, 10 years after the composer’s death.

Comedy on the Bridge was composed as a radio opera for Czechoslovak radio, where it was broadcast in 1935. (Does that broadcast survive?) When Martinů was in the United States and teaching at the Mannes School of Music, the school performed the work in the composer’s presence, in a revised version that uses the translation heard here. So this, too, seems to be a kind of first recording, namely of the composer-approved English-language version. (The previous recordings, sung in Czech, were led by two important conductors: Bělohlávek and Jílek.)

The plot of Larmes moves quickly and holds one’s attention throughout. Briefly, a woman (Éléonore) is in love with a neighbor who has hanged himself. He is named Saturne (like the planet). Satan — whose name of course echoes that of Saturne — encourages her to marry the dead man. On her honeymoon, she falls for a “black racing cyclist” who turns out to be Satan in disguise. (This was an era in which characters who are “black” were considered fascinating, such as in Louis Gruenberg’s The Emperor Jones and Ernst Křenek’s Jonny spielt auf.) The woman commits suicide (with the titular weepy knife), but the Hanged Man revives, which restores her to life. They embrace and emote grandly, he turns out to be Satan, and she runs off stage, weeping and declaring that she will never be understood. (Her mother is around at the beginning and end of the opera; the elder woman adds her voice to the final scene, declaring her love for the devil!)

Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů. Photo: Wiki Common

The music is as brittle and darkly comical as the above might lead you to suspect. Given the prominent role for a seductive devil, one naturally thinks at times of Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du soldat (1918), especially during occasional moments where early 20th-century dance styles intervene. The vocal lines are very conversational, except in moments of (real or imagined or feigned) high passion. In short, the work still feels fresh and almost uncategorizable, close to a century later.

The radio opera (Comedy on the Bridge) has a lot more text, partly because sections of it are spoken rather than sung. This libretto feels proto-existentialist rather than expressionistic, and also resonates with the grim fairy-tale humor of some other Czech works of the era, such as Jaroslav Hašek’s book The Good Soldier Svejk (1921-23) and Otakar Ostrčil’s 1934 opera Jack’s Kingdom (which I favorably reviewed in OperaToday.com).

Briefly, a war is going on, and Josephine has buried her brother near the battlefield. She crosses the bridge to return home, but the sentry at the end nearer her home refuses to let her pass. A brewer comes onto the bridge and is similarly prevented from leaving. He makes a pass at Josephine. Her boyfriend Johnny arrives, as does the Brewer’s wife Eva. Each of the newcomers berates their respective partner, while a Schoolmaster, who is also now stuck there, pesters them with a riddle about a deer in a field surrounded by high walls. Finally, the two couples reconcile, military victory is declared, Josephine learns that her brother is still alive (she inadvertently helped bury some other soldier), and the Schoolmaster admits that the deer in the riddle — clearly a metaphor for the five of them on the bridge — never escapes. They all celebrate and go back to their lives.

The music here is, if anything, even more brittle and discontinuous than in Tears of a Knife, closely matching each new situation. There is little opportunity for legato soaring. But the work would be a great opportunity for students in a college or conservatory opera program, helping them learn to put text across while still maintaining an attractive, solid core of tone.

Martinů gave the older couple a lower range: contralto and bass, whereas the young couple are a soprano and a baritone. The Schoolmaster is sung here, with gentle parody, by a thin-voiced tenor (what is sometimes called a “character tenor”). The performers catch the particular spirit and profile of their respective role.

I was glad to get to know both operas, and recommend them highly to anybody intrigued by the possibilities of making opera new without falling into the trap of making it “grand.”

Indeed, I asked Thomas Svatos, a leading authority on Martinů, about the pointed lack of grandeur in both works. He wrote the following to me, which I’m happy to share with our readers. (He helped with my opening paragraph as well.) “Having the two operas together on a single CD allows us to see Martinů’s change in approach to musical theater from the 1920s to 1930s. During the ’20s, as in Tears of a Knife, he was keen to put on display an attitude of Dadaist irreverence towards high art, as shown by the bizarre, unconventional themes and the occasional American dance number or snippet. By contrast, Comedy on the Bridge, from the ’30s, was part of a series of theatrical works conceived for a wider Czech audience, in which he chose less confrontational themes and more conventional styles, though ones tinged here and there with Czech native elements. In the case of both works, however, we see his aversion to the monumental in theater, as well as his ability to constantly shift in musical style throughout a single work.”

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and the Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is on the editorial board of a recently founded and intentionally wide-ranging open-access periodical, Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal. The present review first appeared, in a somewhat different version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Bohuslav Martinů, Capriccio, Comedy on the Bridge, Cornelius Meister, Elena Psallagova, Esther Dierkes, Stuttgart State Orchestra