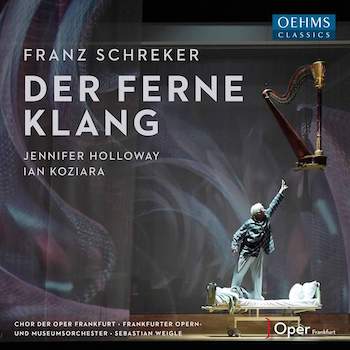

Opera Album Review: “Der ferne Klang” Does Its Thing and Does It Amazingly Well

By Ralph P Locke

I am beginning to suspect that Franz Schreker was the most effective of the many semi-forgotten opera composers who were active in the German lands during the first decades of the twentieth century (that is, ones less well known today than Strauss, Berg, and Kurt Weill).

Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang

Jennifer Holloway (Grete), Nadine Secunde (Old Woman), Ian Koziara (Fritz), Gordon Bintner (Count), Iain MacNeil (Baron), Theo Lebow (Chevalier).

Frankfurt Opera, conducted by Sebastian Weigle.

Oehms OC980 [3 CDs] 137 minutes.

Click here to purchase or to hear a portion of each track.

Europe, in the nineteen-teens and twenties, was a varied scene of vibrant, bubbling cultural life. The whole era was volatile, productive, and also destructive, including as it did all of World War I and the postwar economic catastrophe in Germany.

Europe, in the nineteen-teens and twenties, was a varied scene of vibrant, bubbling cultural life. The whole era was volatile, productive, and also destructive, including as it did all of World War I and the postwar economic catastrophe in Germany.

We tend to be familiar with certain names, works, and trends: the Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Thomas Mann’s novels (Death in Venice, The Magic Mountain), German silent films (The Golem, Nosferatu), the Brecht-Weill Threepenny Opera, and Richard Strauss’s and Igor Stravinsky’s separate and distinctive turns toward a kind of neoclassicism.

But dozens of other important figures, including many composers of remarkable skill and imagination, were active in those two decades, often receiving recognition and encouragement, yet we tend to know less about them today. I have praised here a powerful 1926 ballet score by Egon Wellesz (Die Opferung des Gefangenen, i.e., The Captive Made into a Sacrificial Victim); the work’s world-premiere recording was finally released commercially after it sat for twenty-five years in the radio vaults of the Austrian Radio. I also greatly admired two appealing and psychologically rich operas by Alexander Zemlinsky: A Florentine Tragedy (based on a one-act Oscar Wilde play) and Der Traumgörge (freely translated: Georgie the Dreamer).

Franz Schreker (1878-1933) has been a little luckier than Wellesz and Zemlinsky. Various of his nine operas have been revived in Europe, though much less often in North America. Perhaps the best-known of the operas is the one here reviewed, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound; 1912), in what is, astonishing to admit, its fifth recording (or its sixth, if you include one made back in 1948).

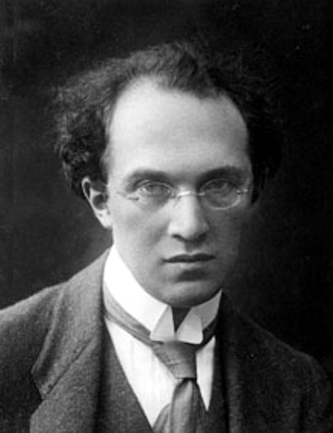

I’d long heard about Schreker but never drenched myself in any of his rather astonishing works. His operas were widely performed in the German-speaking world until the Nazi era. He himself was enormously influential, teaching composition at the Berlin Hochschule (and even heading the school). His many notable students included Berthold Goldschmidt, Ernst Křenek, and Stefan Wolpe. Schreker was deposed in 1932, in large part because his father was Jewish. He died of a heart attack a year later.

Schreker composed in a style that we might call tonality-plus, since it sometimes ventures into recently discovered scales such as whole-tone. His works also invoke traits typical of the entertainment music of the day (e.g., café bands).

Composer Franz Schreker in 1912. Photo:Wiki Common.

The previous recording were conducted by Michael Halasz, Gerd Albrecht, Leon Botstein, and Dirk Kaftan (plus Winfried Zillig, in 1948). Many of these can be heard on Spotify or other streaming services, or tasted (track by track) for free on YouTube. I have heard portions of the Albrecht, which has many fine features, but the reading just released on the Oehms label (and likewise easily accessible through streaming) is consistently strong, under Sebastian Weigle.

The libretto (by the composer) tells of a businessman’s daughter, Grete, who is in love with a composer, Fritz. He, though, goes off into the world in search of a certain special “distant sound” (which gives the opera its title). In the middle of Act 1, Grete, defeated, almost accepts a marriage engagement with the town’s innkeeper, then considers committing suicide, but a mysterious Old Woman appears and leads her away.

In Act 2 (ten years later), Grete has become Greta, a high-level society hostess in Venice. We get to hear a song contest between a count and a “chevalier,” each clearly wanting Greta’s hand. Fritz appears and is horrified to see her living in what he calls “shame.”

In Act 3 (another five years later), the heroine, now known as Tini, has become an impoverished and ailing prostitute, whereas Fritz is the honored, aged, and weary composer of an opera being performed at the court theater. Grete (Tini) attends a performance and is briefly revivified by hearing Fritz’s music. (The music of his opera incorporates materials from other parts of Der ferne Klang, perhaps implying that Fritz is a version of Schreker himself. “Fritz” is, of course, a nickname for “Franz”.) After an extended orchestral meditation on previously heard themes, Fritz, at his desk, tries to rewrite the last act of the opera, Grete enters, they reconcile, and he dies in her arms.

The music is very diverse in manner from moment to moment, always supporting the immediate dramatic effect. Schreker clearly enjoys evoking such things as moonlight on the water (toward the end of Act 1), Hungarian “Gypsy” music (in the Act 2 bordello), and overlapping bird songs (before the final scene). There are recurring themes and passages that sometimes come back literally, other times reworked and further developed. The melodic lines — in the vocal parts and in the orchestra — are often attractive, sharply characterized, and memorable. (That is, when the vocal parts are not freely declamatory over highly expressive orchestral music.)

Much in the music is distinctive and refreshing. Of the beginning of Act 2, Christopher Hailey observes in Grove (OxfordMusicOnline): “the collage of onstage and offstage vocal and instrumental ensembles, polyrhythmic juxtapositions, layering of styles and improvised sounds…bears comparison with contemporaneous experiments by Ives and with the emerging visual vocabulary of the cinema.” That passage also reminded me of the diverse social whirl that opens, and recurs in, Stravinsky’s Petrushka (a work that Schreker likely did not yet know).

At times. while listening, I thought of Puccini, which I admit is a strange association when hearing German words being sung or, as occurs a few times, spoken. But lots of other “comparables” (as they say in the real-estate business) occurred to me at various moments: Weill during the Count’s contest-song, Janáček at several points later in Act 2. I mention these brief resemblances mainly in order to place Schreker’s style and manner for people who have not encountered his music, not to put him down as derivative.

Jennifer Holloway as Greta and Ian Koziara as Fritz in the Frankfurt Opera production of Der Ferne Klang. Photo: Barbara Aumüller.

The cast here is international, but the singers sound very well-schooled in the German language and clearly know what they are singing about, even if certain subtleties of diction elude them (e.g., the soft “ch” sound in “ich”). Rich yet steady-toned Jennifer Holloway, whom I raved about in the world-premiere recording of Gounod’s Le tribut de Zamora, is the protagonist, Grete/Greta/Tini. To my great pleasure, she is heard in nearly every scene. Ian Koziara, sounding heroic and clear at all times (and wonderful up high), is Fritz, who loves her but loves art more.

More than a dozen others take various smaller roles, including baritone Gordon Bintner, who brought the problematic role of Junior convincingly to life in Kent Nagano’s 2017 recording of Bernstein’s A Quiet Place. Their voices are always appropriate to the character they’re portraying, even the renowned Nadine Secunde, whose vocal unsteadiness at age 65 would be painful to report except that it suits the role of the mysterious “Old Woman.”

Sebastian Weigle has the Frankfurt chorus and orchestra under total control: every bar propels the drama and, with unexpected sound-combinations, delights the ear. Photos in the booklet show what seems like a very effective staging, yet the sound is as detailed and well balanced as can be expected in a recording made during staged performances. The voices are somewhat more prominent than the orchestra, perhaps in order to minimize noises from the audience, but plenty of orchestral color comes through anyway.

I am beginning to suspect that Schreker was the most effective of the many semi-forgotten opera composers who were active in the German lands during the first decades of the twentieth century (that is, ones less well known today than Strauss, Berg, and Kurt Weill). I liked the work, and felt swept up in it, even more than by Korngold’s Das Wunder der Heliane, which, in comparison, feels ungainly and pretentious (though I still like it). Der ferne Klang does its thing and does it well. Like, again, much Puccini. I urge you to get to know this intriguing and extremely accessible opera, even though it’s about people who aren’t very endearing.

The work is sensibly given one CD per act, but this increases the price. (If Act 2 had been split, the work would have fit onto two CDs.) The libretto is in German only, followed by over 30 pages of performer biographies. Adding a parallel English translation to the libretto would have used those 30 pages more profitably. And it would have given the recording a decided edge; none of the others that are currently available, as far as I can tell, translate the libretto.

Jennifer Holloway as Greta (in red on floor) in the Frankfurt Opera production of Der ferne Klang. Photo: Barbara Aumüller.

Also, the names of the characters should have been clarified in a user-friendly manner. Some of them are worded differently in the libretto than in the cast list (e.g., “His Wife” and “The Mother” are the same person) or differently in two places in the libretto. We are not told that the “Voice of a Man” coming from a gondola turns out to be that of the Count. And someone should have added vertical lines to indicate passages of singing by different characters that go on simultaneously. Even this would not have been enough for the beginning of Act 2: the simultaneously sung passages should have been set in parallel, across two pages, not placed one below the other.

The libretto also contains one absolute blooper: a stage direction in the middle of a long solo by Greta prints the Count’s name in large font, thereby giving the impression that he sings all the rest of her solo. I noticed similar problems in the printed libretto for a previous release by Oehms (a Vainberg opera, sung in German). I still yearn for the large, helpfully laid-out libretto pages in LP opera sets from, especially, London/Decca. (Translator Peggie Cochrane, clearly the mastermind behind them, hereby receives my belated gratitude.)

The Albrecht recording remains available at a bargain price (on 2 CDs), though I can’t tell if it contains a libretto (much less a translation). The soprano, Gabrielle Schnaut, has an edgy, quavery voice that is often just a wee bit under pitch, making her sound almost consistently woebegone. But, as Roger Hecht reported in American Record Guide in January/February 2014, “Thomas Moser is an excellent Fritz…Roland Herrmann makes a star vehicle of the Count’s song, and the many minor characters carry out their roles well.” The portions I listened to show the advantages of having native German-speakers in the many passages involving quick verbal exchanges over continuous orchestral textures.

Apparently the opera has never been released on DVD (ideally with subtitles), though there is a fine version of Schreker’s Die Gezeichneten, conducted by Kent Nagano.

I am delighted to have gotten to know this amazing and highly enjoyable opera from an admirable composer (who, I should have said, was in this opera and all his subsequent operas, his own skillful librettist)! And to have a fuller sense, now, of the cultural riches of those years in Europe just before, during, and after World War I.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review is a lightly updated version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide, and is included here with that magazine’s kind permission.

Tagged: Der ferne Klang, Franz Schreker, Jennifer Holloway, Oehms