Classical CD Review: A Ballet of Human Sacrifice — Set in Ancient Mexico or Post–World War I Germany?

By Ralph P. Locke

Egon Wellesz’s Weimar era critique of the cruelty of nations that are victorious in war still rings hauntingly true.

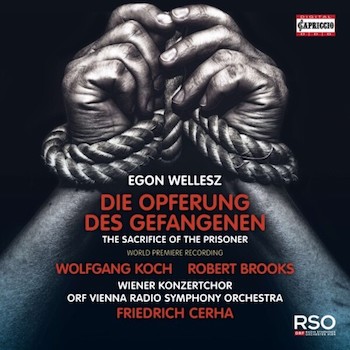

Egon Wellesz: Die Opferung des Gefangenen (ballet score)

Egon Wellesz: Die Opferung des Gefangenen (ballet score)

Wolfgang Koch (Field Commander), Robert Brooks (Prince’s Shield Bearer), Ivan Urbas (Head of the Council).

Vienna Concerto Choir, ORF Vienna Radio Symphony, conducted by Friedrich Cerha.

Capriccio 5423—56 minutes

Die Opferung des Gefangenen (The Sacrifice of the Prisoner) is a time capsule, twice over. The work comes from Vienna, 1925. The recording — a world premiere — was made in 1995. Over 25 years later — and nearly a century after the work’s first performance — the recording has finally been put out on CD, allowing us to hear a work that is deeply shaped by the cruelty of the victors of World War I.

The composer is Egon Wellesz (1885-1974). This release comes on the heels of numerous other recordings of Wellesz works that have been released on CD, including nine symphonies (that magic number!), some string quartets, and two concertos. A set of imaginative Robert Browning sonnets, in German translation, was recorded by Renée Fleming and the Emerson Quartet and, like so many classical recordings nowadays, can be heard on YouTube and other streaming services.

Egon who?

Well, to scholars and music lovers who, like myself, are “of a certain age,” Wellesz was a respected, well-connected, and much-published musicologist from Austria who ended up teaching at Oxford. His carefully constructed and influential writings and scholarly editions deal with such diverse topics as Byzantine (Eastern Orthodox) Christian chant, Baroque opera, Fux (the eminent 18th-century Viennese composer-theorist), and Schoenberg (who was Wellesz’s own first composition teacher).

But Wellesz was also a composer of great skill and imagination, whose works are getting renewed attention, much like those of other composers who, like him, mostly hewed to a late-tonal or expanded-tonal style. If you are attracted to the music of Hindemith, Honegger, Janáček, Zemlinsky, or Korngold, Wellesz’s name is another one you will want to be looking for. His music was new to me, but I like what I have heard. Quartet No. 4, for example. Actually, Die Opferung des Gefangenen is more accessible than many other works by Wellesz (or by, say, Hindemith or Zemlinsky). But first some basic info about the work.

The title page describes Die Opferung des Gefangenen as “A Cultic Drama for Dance, Solo Voices, and Chorus [and Orchestra], after the Transcription by Eduard Stucken of a[n Ancient] Mexican Dance-Play, Arranged and Set to Music by Egon Wellesz.”

Die Opferung was written in 1924-25 and performed in Cologne, Magdeburg, and Berlin in 1926-30. It then vanished until it was revived in 1995 — apparently as a concert piece without dancers, sets, or costumes (hence with less “cultic” quality) — in the performance that is belatedly released here.

Egon Wellesz in the 1920s — a truly fine composer.

Dancers are central to this work as originally conceived and performed. They carry out the action, and the chorus, for the most part, sings about what is happening or will next happen. Solo vocal parts are assigned to a few characters. I gather that each is the “double” of a character whose role is also being danced. The captive prince mentioned in the title — the prisoner who will eventually be “sacrificed” (put to death) — has no singing double: his role is utterly mute, indicating, I assume, his powerlessness. But that also forces the audience’s attention all the more on his dancing and gestures.

I would love to see a full production of this fascinating and colorful work, which, for me, contains echoes of certain of Brecht’s pointedly didactic plays (Lehrstücke), such as Der Jasager (1930), as memorably set by Kurt Weill. That work likewise involves the ethical conundrum of whether an individual — there, a schoolchild — should get sacrificed for some understood “greater good.”

The plot comes from an Aztec or Mayan ritual play and involves a tribal chieftain who, with his people, forces the leader of a conquered tribe to don royal robes and to marvel at and enjoy the pleasures and riches of the victor’s realm. And then the local people, having both celebrated and humiliated the vanquished chieftain in this manner (I am reading some motivation into their actions), lead him to the spot where “Eagles” and “Jaguars” (i.e., armed troops of the victorious chieftain) kill him behind their shields — echoes of the final moment in Strauss’s Salome (1905)! — and then place his corpse on the altar as the chorus sings hymns of praise to this “hero” whose spirit is now rising and will takes its place on a throne next to those of his worthy ancestors.

From today’s point of view, this may all sound hopelessly exoticizing and demeaning. But Wellesz reportedly considered the work a comment on the decline of Western civilization, as represented by the disasters of World War I. These disasters included, in the war’s aftermath, Germany’s punishing economic collapse, which was already, by 1925, spurring the rise of fascism. Hitler would seize power eight years later and drive Wellesz and many other notable musicians into exile. (Wellesz, a devout Christian, was of partially Jewish origin.)

The music for Die Opferung is sharply profiled, with frequent ostinato rhythms and the chorus often singing in unison. I was reminded at times of Orff’s Carmina Burana (1937), some grim moments in Weill’s Mahagonny (1930), or the Act 1 chorus from Puccini’s Turandot (1926), in which the people of Peking urge the executioner to kill the Princess’s next victim.

Some of the moments of wailing and keening for orchestra or unaccompanied voices are similar in mood to passages in Debussy’s The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (1911). An early passage for full chorus (track 4) and the concluding chorus (track 19) make powerful use of short poetic lines, in the manner of the hieratic finale for men’s chorus to Busoni’s Piano Concerto (1904), whose text praises the power and deeds of Allah (God). Other listeners will surely pick up different echoes and parallels.

The orchestral prelude gives a compact sense of the work’s stylistic diversity and vividness. It opens with a pentatonic passage for unison brass over drumrolls that reminded me of ’50s Hollywood “sword and sandal” epics set in biblical or other ancient days — a time period for which “primitive” and emphatically repeated materials were often thought peculiarly appropriate. Of course, some leading Hollywood composers (e.g., Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold) came from the same Central European cultural world as Wellesz, so the stylistic kinship may be quite natural!

The prelude continues with a rich, march-like string passage reminiscent of Mahler and then dissonant, highly rhythmic music for full orchestra in the manner of, say, Honegger.

This diversity of style continues throughout the work and, rather than a deficiency, feels like a consistently appropriate way of responding to the shifts in the scenario, such as the chorus’s respectful thoughtfulness after this stage direction: “The gesture made by the [captive] Prince expresses a noble decisiveness and a readiness to face death. His warriors display the same attitude. As a result, the victors, from this point on, no longer regard him as an enemy — rather, as a being who has been dedicated to the gods as a holy sacrifice.” (You can hear the beginning of each track here.)

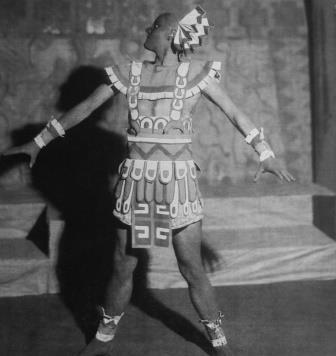

In the absence of staged performances (or a video), we have this recording, a richly informative booklet-essay, the full libretto (but in German only) with the detailed stage directions from the score (all helpfully track-numbered), and a photo of a magnificently costumed 1927 production from Magdeburg. The photos, and others that I have found online, suggest that “Early Mexico” was here not viewed as exotically “Other.” Rather, it was considered archetypal of all societies, not least modern-day Europe. True, some characters may have feathered headdresses, but their clothing is highly abstract and geometric, in an Art Deco or De Stijl manner. And the dancers’ bodies clearly projected the nobility and the threatening violence that seem always to be latent in the human soul.

A still from the 1925 premiere of Die Opferung des Gefangenen. Photo: Forbidden Music.

All of this, and especially the synopsis, helped me to reconstruct the work in my mind and to feel strongly involved throughout. Fortunately, my German is pretty good — others may feel semi-lost. The Capriccio firm should try a bit harder to bring their fine wares to the attention of music lovers outside the German language-region.

The booklet also crucially misplaces an apostrophe: the tenor role is not “The Princes’ Shield Bearer,” in the plural. He is the shield-bearer of a single prince: namely the foreign warrior who will eventually be put to death.

The conductor, Friedrich Cerha, is himself a composer, best known for having completed Berg’s final opera, Lulu. The performance is at once powerful and, in its many colors, quite varied. The vocal soloists are steady and forthright: they sing somewhat impersonally, as is appropriate in a highly ritualized work of music theater.

The acoustic is natural: the fuller passages do not distort or overwhelm. This means that the dynamic range is quite wide. I turned up the volume in quieter moments, and tried to remember to turn it down quickly when the quiet passage seemed to be ending, in hopes of sparing my ears when the next fortissimo arrived.

The musical style, as I suggested above, is immensely communicative. Wellesz was a truly fine composer: this one composition is surely on the level of his best musicological work (which is to say first-rate). I recommend Die Opferung des Gefangenen and its recording to anybody interested in the “freely tonal” composers of the 20th century. As a commentary on the proclivities of humankind, it remains as true as ever.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Bertolt Brecht, Capriccio, Die Opferung des Gefangenen, Egon Wellesz, Friedrich Cerha, Ralph Locke