Jazz Album Review: They Must Have Been “hEARoes”

By Michael Ullman

The trio on hEARoes is enthralling; it doesn’t sound like anything I have heard.

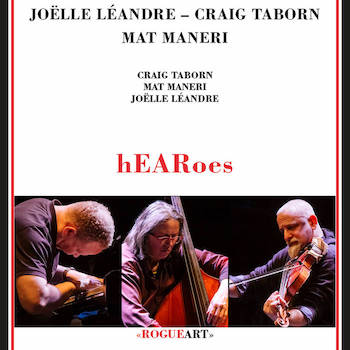

Joëlle Léandre, Craig Taborn, Mat Maneri, hEARoes (RogueArt)

In the mid-’80s I was sent a disc by the French bassist Joëlle Léandre. I had never heard of her, but I was astonished by the power and ingenuity of her playing. I mentioned her to a bassist friend of mine and he replied excitedly, “She’s a goddess!” The goddess has recorded widely since, including with the elite of the avant-garde world, such figures as Derek Bailey, Steve Lacy, Anthony Braxton, George Lewis, William Parker, and Irene Schweizer.

In the mid-’80s I was sent a disc by the French bassist Joëlle Léandre. I had never heard of her, but I was astonished by the power and ingenuity of her playing. I mentioned her to a bassist friend of mine and he replied excitedly, “She’s a goddess!” The goddess has recorded widely since, including with the elite of the avant-garde world, such figures as Derek Bailey, Steve Lacy, Anthony Braxton, George Lewis, William Parker, and Irene Schweizer.

Léandre’s made at least 10 solo bass albums. Elsewhere she specializes, it seems, in duos and trios playing wholly improvised music. She often sounds fierce to me, so I was amused when in 2016 she released a disc called Unleashed with a group she named her Tiger Trio. The follow-up trio album, also with Myra Melford and Nicole Mitchell, is called Map of Liberation. It’s an 11-piece guide to mental and social health that begins with “Patience” and ends with “Honesty.” On the less programmatic side, she has recorded nine solo pieces called “No Comment” (on an album of the same name), some of them performed at the Vancouver Jazz Festival.

Léandre’s new disc is a free jazz collaboration with violist Mat Maneri and pianist Craig Taborn. Its seven movements, one for each letter in its title, were recorded live at the Festival Sons d’hiver (Sounds of winter) in Ivry-sur-Seine, France. Léandre had recorded with Maneri in 2011. On the other hand, she hadn’t previously played with the pianist, the well-known Craig Taborn, whom many of us first heard in the mid-’90s in James Carter’s bands. (To complicate matters, Taborn was the pianist on Mat Maneri’s Pentagon from 2005.) Yet there’s no hesitation even in “h,” the first number, which begins with the bassist bowing a simple two-note phrase, and then seeming to comment on herself, while Maneri and Taborn enter with spare notes like sprinkles of rain. Maneri plays a sweeping upward moving phrase early on, and one hears Taborn echo it. Hearing as well as declaiming is obviously their thing. Maneri and Léandre sometimes echo each other: at around three and a half minutes of “h” they provide long bowed tones in a gradual crescendo that seems to challenge Taborn’s solo. Mostly the three play together, willfully changing tempos and dynamics in a way that sounds natural and, to my ears, coherent.

At the beginning of “O,” Léandre again opens, this time with a plucked note that she moves via a short glissando. Immediately the piece becomes a duet between Taborn and the bassist, diversified after two and a half minutes when Léandre switches to bowing and Maneri enters while Taborn temporarily sits out. It’s as if the pianist were waiting to pounce, which he does — after listening, using his ears as the title suggests. This piece may have been conceived as a series of duets because soon Maneri and Taborn are playing off each other while their leader sits out. “R,” though, begins with a forcefully ringing statement on piano. Taborn stops and Léandre plays a solo.

I am not sure to what extent these variations in texture were planned. The effect is of quicksilver conversations, sometimes delicate, sometimes strongly opinionated, as in “O” which has the bassist thumping, Taborn stomping, and Maneri playing alternately weeping phrases and tight staccato notes. It’s a bit raucous, but each member is clearly listening to the other two. By three minutes, the strings are down to screeching intensely. Yet these hEARoes can also be surprisingly lyrical. Their playing is precise, their interactions confident and significant. The session is always intriguing, whether the players are scurrying about, or seeming to hide behind each other, or just competing for attention. The trio is enthralling; it doesn’t sound like anything I have heard.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.