Classical Album Review: A Panorama of Piano Music from Berlioz’s World

A fascinating CD packed full of little-known works by composers who knew Berlioz, including his onetime fiancée Camille Moke and a youngish Franz Liszt.

By Ralph P. Locke

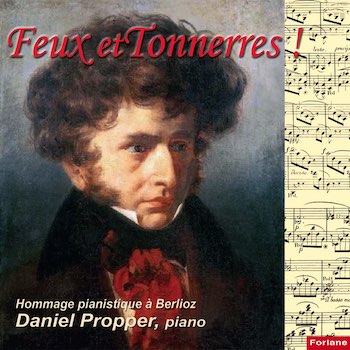

Feux et Tonnerres! (19th-Century French Piano Music)

Works by Damcke, Dillon, Doehler, Haslinger, Heller, Hiller, Liszt, Moke, Morel, Prudent, and Ritter

Daniel Propper, piano

Forlane 16900—79 minutes

To purchase a digital download or listen to the beginning of each track, click here.

Here is a disc full of what are mostly, I bet, world-premiere recordings. The CD’s title translates to “Damn It All! [literally: Fire and Thunder!]: A Pianistic Homage to Berlioz.” Daniel Propper, the pianist who has put this unusually imaginative keyboard tapestry together, is from Norway but received advanced training at Juilliard and then in Paris. He made a recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations nearly two decades ago. Since then, he has released a recording of the complete Grieg Lyric Pieces and of songs by Offenbach (with two fine, stylish female singers). Plus a CD of musical works inspired by the French poet Lamartine and a similar one focused on the British poet Byron. Unfortunately, the Lamartine and Byron discs feature a baritone whose tone is often unsupported.

Here is a disc full of what are mostly, I bet, world-premiere recordings. The CD’s title translates to “Damn It All! [literally: Fire and Thunder!]: A Pianistic Homage to Berlioz.” Daniel Propper, the pianist who has put this unusually imaginative keyboard tapestry together, is from Norway but received advanced training at Juilliard and then in Paris. He made a recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations nearly two decades ago. Since then, he has released a recording of the complete Grieg Lyric Pieces and of songs by Offenbach (with two fine, stylish female singers). Plus a CD of musical works inspired by the French poet Lamartine and a similar one focused on the British poet Byron. Unfortunately, the Lamartine and Byron discs feature a baritone whose tone is often unsupported.

Here Propper is neither assisted nor hindered by another artist. What we get is very straightforward readings of eleven pieces, none of which I had ever before encountered. All the pieces have some demonstrable or arguable connection to Berlioz: a piece was dedicated to him, or composed by a friend of his, or simply has a title that is similar to that of a Berlioz work (Berthold Damcke’s La Nuit d’été). One of the pieces is by the sixteen-year-old Camille Moke, the sterling pianist who would three years later (in late 1830) become his fiancée but then dump him for a wealthy businessman, Camille Pleyel. (She would go on to have a major career as pianist and as professor at the Brussels Conservatory, under the name Marie Pleyel.) Another piece is by a female pianist-organist I had never heard of, Juliette Dillon.

All of this will be fascinating for collectors with a strong interest in the instrumental music of the nineteenth century or in women composers. Few of the pieces shine new light on Berlioz, much less show any influence from his highly distinctive and sometimes experimental style. Nearly all of these pieces are extremely “normal” in harmony and phrase structure, and many of them are loaded (some will say overloaded) with the decorative passagework so typical of much keyboard music of the era. It doesn’t help that Propper’s readings are, as I said, very straightforward, with only slight adjustments in tempo, adjustments, and touch. I wonder whether a pianist more impulsive by temperament might have helped the pieces in this quasi-recital make more of an impression. Oddly, the tracks that I listened to from Propper’s Grieg recordings employ more freedom than what he demonstrates here. Perhaps he was too concerned this time around to present unfamiliar music without personal intrusion.

Camille Moke was a celebrated pianist in the 19th century who had been engaged to Hector Berlioz, but married Camille Pleyel, the piano manufacturer.

That said, I was gratified to hear some tracks, including an 1835 Rêverie by Ferdinand Hiller (a friend of both Mendelssohn and Berlioz during the 1830s), a Caprice symphonique by Stephen Heller (a close friend of Berlioz’s old age), a Dance of the Fairies (dedicated to Berlioz) by Emile Prudent, a stirring Funeral March composed in Berlioz’s memory by Théodore Ritter (a piano prodigy whose original family name was Prévost and whose father was a friend of Berlioz’s), and Franz Liszt’s ingeniously elaborated version (from the mid-1840s) of the recurring theme from the Symphonie fantastique: Liszt entitles the piece L’Idée Fixe: Andante Amoroso. For an insightful observations on Liszt’s piece, I recommend the discussion in Peter Bloom’s recent book Berlioz in Time: From Early Recognition to Lasting Renown. That book is available Open Access (without fee or password), thanks to a subvention from the New Berlioz Edition Trust.

People interested in the ever-intriguing problem of program music (instrumental music that seeks to evoke images or ideas, or even to suggest a narrative) will want to get to know Charles Haslinger’s “The Phantom,” Prudent’s aforementioned fairy-dance, and Juliette Dillon’s “The Lost Shadow” (based on a tale by E. T. A. Hoffmann: presumably the same one that would later form the basis of the last act of Offenbach’s final opera, The Tales of Hoffmann).

The sound is clean and clear. The booklet-essay by Olivier Feignier, smoother in the original French than in the English translation, is full of helpful information. It seems only to be available with purchase of the CD; the Presto Classical site has the release as a download, but specifically states: “No digital booklet included.”

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is on the editorial board of a recently founded and intentionally wide-ranging open-access periodical: Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal. The present review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Berlioz, Camille Moke, Daniel Propper, Feux et Tonnerres!