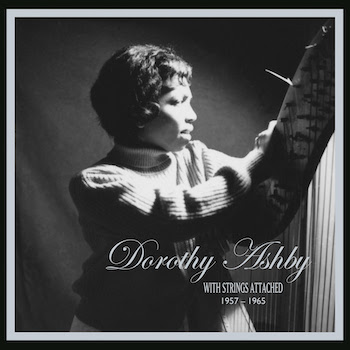

Jazz Album Review: “Dorothy Ashby – With Strings Attached, 1957-1965”

By Steve Provizer

A rare Black female instrumentalist bandleader, whose improvisations on the harp were the equal of any horn, Dorothy Ashby deserves a respected place in jazz historiography.

Dorothy Ashby – With Strings Attached, 1957-1965 — New Land Records.

Trumpet, trombone, and reeds have long dominated jazz combinations, but “off” instruments have also staked their claim. Allen Michie recently wrote about bassoon, Adrian Rollini had the Goofus, Rufus Hartley coaxed jazz out of bagpipes, and Steve Turre performed with conch shells. Then there are slightly less “off” axes: Rahsaan Kirk’s manzella and stritch, Kiane Zawadi (Bernard McKinney) on baritone horn, and Cy Touff on bass trumpet. Since the ’50s, the harp (not the harmonica) has been a fairly steady presence in jazz, due in large part to the foundational efforts of Dorothy Ashby.

There are six LPs in this box-set, covering Ashby’s early work from 1957 to 1965. I’ll look at the music along with interspersing more biographical material than I normally do. Readers should learn more about the protean, intrepid Ashby. (I gratefully acknowledge Shannon J. Effinger’s extensive album notes.)

Dorothy Ashby, née Thompson, was born in 1932. She was a Detroit native, the daughter of jazz guitarist Wiley Thompson. Detroit’s integrated Cass Technical High School established what became the longest-standing harp program in the US. Ashby was given the opportunity to double on piano and harp. Ron Carter and Donald Byrd were her classmates; Alice (McLeod) Coltrane attended a few years later. In 1947, Ashby was the only Black member of the Cass Symphony orchestra.

Apart from harp, Ashby sang and played sax, viola, and violin. Along with playing in the orchestra at Wayne State University, she performed at recitals and often sang folk songs on local radio programs to help pay her tuition.

In 1951 she married drummer John Ashby, who also attended Cass. They formed a trio, which, despite Ashby’s skills, had trouble getting gigs. Even though classical music’s best-known harp soloists were men (Nicanor Zabaleta, Carlos Salzedo, Harpo Marx), the harp has often been considered a “female” instrument. And jazz has been hard on women, especially when they fronted a band and/or weren’t singers. These are other reasons that the instrument never broke completely into the jazz mainstream. For example, it’s a pain to schlep around.

For those unfamiliar with the instrument, the pitch of the strings can be changed by a set of seven foot pedals that can raise pitch a half or whole step. At gigs, Dorothy and John put two large microphones on the harp’s soundboard and placed another inside its soundbox. According to the liner notes, “the inner body of Dorothy’s harp was often carpeted, which enhanced the acoustics. She was often known to play her harp with torn pieces of carpet stuck to her shoes.”

When Count Basie’s band came to Detroit in 1957, Frank Wess, the group’s flutist and reed player, heard the trio in a club and was impressed enough to invite Ashby to New York City to record. The result was Ashby’s debut album as leader, The Jazz Harpist, for the Regent label. Other Basie-ites completed the rhythm section: bassists Eddie Jones and Wendell Marshall and drummer Ed Thigpen. Jazz Harpist was recorded in one day — there was no rehearsal time. Ashby then signed with Prestige Records in 1958 and released Hip Harp. Wess also plays on this recording, with Art Taylor on drums and Herman Wright on bass. That same year, Ashby released In a Minor Groove on the New Jazz label, with Roy Haynes replacing Art Taylor on drums. The tunes are mostly standards, all in a minor key.

These albums — all in this release — follow the template for what Ashby would record until 1965. The tunes are a combination of standards and originals written by Ashby. Wess always on (virtuoso) flute or Ashby take the head alone or they double on it. They each take solos and sometimes trade 4’s, 8’s, etc. At middle and up tempos, the music swings lightly, while ballads can sometimes be bogged down in excessive glissandi. There is a pleasant quality to the music which, while soothing, is not soporific. The tonal nature of the harp is such that it’s difficult to make it sound rough. Even when Ashby tries to put some edge on the sound there is always something relaxed at the core. This does truncate the emotional range of the instrument a bit. It is also an aspect of the harp that makes Ashby’s later forays in spirituality –and those of Alice Coltrane- — seem very natural.

In the early ’60s, Dorothy worked at WJR (760 AM), a 50,000 watt Detroit radio station. She played harp with the Jimmy Clark Orchestra for the Jack Harris show and performed folk songs with the orchestra for the Bud Guest program, Guest House.

In 1961, Ashby recorded Soft Winds: The Swinging Harp of Dorothy Ashby for the Jazzland label. Soft Winds features Ashby with Herman Wright on bass, drummer Jimmy Cobb, and Terry Pollard on vibes and piano. Pollard is another pioneer in the bop and post-bop world. A Black woman, also from Detroit, she spent five years with vibes player Terry Gibbs and played with Bird, Miles, Coltrane, and others. To some degree, she takes the role that Wess did on previous recordings, but Pollard and Ashby alternately push each other and lock in together. For me, this is the most purely swinging of all the albums (aside from the tune “Laura,” which Ashby gussies up a bit too much). Cobb in the drum chair doesn’t hurt.

Dorothy Ashby, released the following year in 1962, features a trio, with bassist Wright and her husband on the drums, billed as “John Tooley.” That year, Dorothy and John started Detroit’s Ashby Theatre Company (Ashby Players). It was financed almost entirely from their savings: it took about five years before its first production was mounted in 1967. The work of the Ashby Players addressed issues that impacted the Black community in Detroit — ghetto life, sex, racism, and welfare. John wrote the scripts, Dorothy composed the lyrics and music and played the piano and harp for most productions.

In 1964 and 1965, Dorothy appeared on the Tonight Show. In 1965 she was gigging at Detroit’s Café Gourmet and released her next album, The Fantastic Harp of Dorothy Ashby. It features drummer Grady Tate, Richard Davis on bass, percussionist Willie Bobo, and trombonists Jimmy Cleveland, Quentin Jackson, Sonny Russo, and Tony Studd. The difference between this and previous recordings was the presence of a brass section (brass players don’t solo here), more elaborate arrangements, and the addition of Bobo, which gives the rhythm an extra bounce as well as a Latin tinge.

While all this was going on, Dorothy regularly wrote jazz reviews for her column for the Detroit Free Press — “Dorothy Ashby on Records.”

At this point, Richard Evans becomes an important person in Ashby’s musical life. Evans was a bassist and a producer and arranger for Cadet Records, a jazz imprint of the Chess label. Chess Records rereleased Dorothy Ashby, now titled I Love Dorothy Ashby. Unfortunately, the label replaced the original artwork with an image of a Caucasian woman posed with a harp.

Although this album marks the end of the music on this six-CD release from New Land Records, Ashby’s career continued and thrived.

Evans took Dorothy in new, non-mainstream-jazz directions. In 1968, they collaborated on Afro-Harping which infused elements of funk, soul, and the blues. Dorothy’s Harp was released a year later, in 1969. Odell Brown is on Fender Rhodes and Lennie Druss on flute and oboe. Evans uses technology like synth, wah-wah pedal, and tape delay. Dorothy sounds like Dorothy, but what whirls around her is a lot different than before.

The Rubaiyat of Dorothy Ashby, released in 1970, is the only recording solely composed of Ashby’s original compositions. She sings lyrics drawn from Omar Khayyam. Her voice is lovely. She also plays the koto, a 13-stringed Japanese instrument; the kalimba; and, although the pianist is not credited, I believe it is Dorothy doing some excellent work. This is a recording with significant spiritual content and there is a lot of modal playing, so it bears some similarity to Alice Coltrane’s work in that era.

In the early ’70s, the couple moved to L.A., where John had success as a writer for television shows like The Jeffersons between 1975 and 1977. Dorothy found session work throughout much of the ’70s. They included Stevie Wonder’s tune “If It’s Magic” (1974, replacing Alice Coltrane), +’Justments from singer and songwriter Bill Withers (1974), Bobbi Humphrey’s Fancy Dancer (1975), Sonny Criss’s release Warm & Sonny (1977), Freddie Hubbard’s Bundle of Joy for Columbia Records (1977), Wade Marcus’s Metamorphosis for ABC/Impulse (1976) and Minnie Riperton’s album Adventures in Paradise (1975).

Dorothy is the sole performer on her final two albums as a leader — Django/Misty and Concierto de Aranjuez — released in 1984 on Philips Records. In 1986, at age 55, Dorothy Ashby died of cancer.

Surrounded by jazz as a young girl and enhanced by the training on harp she received at Cass Tech, Dorothy formulated a vision of how the harp could be used in a jazz environment. She was not the only notable harpist of her era. Betty Glamann, Corky Hale, and slightly later, Alice Coltrane were all accomplished musicians. But none was able to fulfill the dictates of mainstream jazz so completely as Ashby. A rare Black female instrumentalist bandleader, whose improvisations on the harp were the equal of any horn, she deserves a respected place in jazz historiography.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.