Film Review: Two “Gialli” Gems from 1972 — “All the Colors of the Dark” and “The Case of the Bloody Iris”

By Nicole Veneto

All the Colors of the Dark and The Case of the Bloody Iris are underrated giallo gems worth seeking out, representing not only the best of the genre, but sex symbol Edwige Fenech’s onscreen magnetism at its strongest.

Note: To accompany her review of Dark Glasses, the latest film from Italian horror visionary Dario Argento, Nicole Veneto wanted to salute two giallo classics that are turning 50 this year. Critic Ed Symkus opened the door when he sent in a piece that praised films from “three bona fide innovators, three singular directorial voices” released in 1972: Ken Russell’s Savage Messiah, Bob Rafelson’s The King of Marvin Gardens, and Brian De Palma’s Get to Know Your Rabbit. Other Fuse critics contacted me, wanting to sound off on their favorites from that year. So three more homages to films from 1972 arrived: Marjoe, Pink Flamingos, and Silent Running. Well, the clamor to do justice to the year did not cease, so along came salutes to four additional films, The Getaway, Last House on the Left, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, and What’s Up Doc? — Editor Bill Marx

All the Colors of the Dark (Tutti i colori del buio) directed by Sergio Martino and The Case of the Bloody Iris (Perché quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer?) directed by Giuliano Carnimeo

Edwige Fenech being tortured in All the Colors of the Dark (1972)

Paraphrasing the sage advice of French dramatist Victorien Sardo, Alfred Hitchcock (in)famously quipped that the key to creating suspenseful cinema is to “torture the women!” “The trouble today is we don’t torture the women enough,” he added, an assessment hardly any truer now than it already was the director’s time. Whether you take this statement as a dark indicator of Hitch’s personal attitudes toward women or another one of his verbal provocations, it’s nonetheless true that female agony and suffering has always made an indispensable contribution to cinematic spectacle. This is invariably true of Hitchcock’s thrillers and everything that came after Psycho, but it’s also a key component to those ultraviolent and opulently shot Italian murder mysteries that make up the giallo genre.

A foreign predecessor to the American slasher, Italian giallo (literally meaning “yellow,” a holdover from the yellow paperback pulp mysteries many movies drew their plots from) peaked in the early ’70s with films such as Dario Argento’s 1970 debut The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo) — a viewing of which allegedly prompted Hitchcock to say, “I’m starting to fear the Italian” — and Mario Bava’s A Bay of Blood (Ecologia del delitto) in 1971. These tales of black-gloved killers inventively butchering beautiful women (and men) against lavishly baroque set pieces pushed Hitch’s advice to new, more violent extremes. Though Bava and Argento are considered the foremost giallo directors of the era, they were by no means the only notable contributors. An entire generation of Italian horror directors including Sergio Martino and lesser-known filmmakers like Giuliano Carnimeo made equally stunning giallo films as gorgeously photographed as Bava’s Technicolor output and operatically staged as Argento’s celluloid nightmares.

As with the American slasher, giallo films featured their own cadre of scream queens, the most memorable being Algerian-born Italian sex symbol Edwige Fenech. Combining Barbara Steele’s cat-eyed gothic beauty with Brigitte Bardot’s simmering European eroticism, Fenech appeared in nearly a dozen gialli through the late ’60s into the early ’90s. After a turn in Bava’s 1970 mystery-thriller Five Dolls for an August Moon (5 bambole per la luna d’agosto), Fenech starred in several Sergio Martino gialli beginning with 1971’s The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh (Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh) opposite Spaghetti Western favorite George Hilton, whom she’d make two more gialli with in 1972: Martino’s psychosexual tour de force All the Colors of the Dark (Tutti i colori del buio) and Carnimeo’s sole contribution to the genre The Case of the Bloody Iris (Perché quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer?).

A scene from 1972’s The Case of the Bloody Iris.

In both films, Fenech plays an emotionally tortured young woman whose involvement in New Age, quasi-Satanic sex cults makes her the target of a deranged psycho killer. All the Colors of the Dark follows Jane Harrison (Fenech), a Londoner haunted by resurfacing night terrors of her mother’s unsolved murder after a car accident causes her to miscarry. Hilton plays Jane’s paramour Richard, a pharmaceutical suit whose solution to Jane’s mental agony is to ply her full of sleeping pills. Against Richard’s express wishes, Jane’s sister, Barbara (giallo regular Susan Scott), sets her up with an agonizingly unhelpful psychoanalyst (George Rigaud), to whom she relates vivid but fragmented memories of a man with piercing blue eyes who may have something to do with her mother’s death. When pills and psychiatry fail to separate dreams from waking reality, Jane turns to her new neighbor Mary (Marina Malfatti) for guidance. Her solution? Invite Jane to participate in a Black Mass obviously!

Needless to say, things get worse for Jane once she subjects herself to the sect’s increasingly disturbing and sexualized rituals. When one such ritual results in Mary’s death, Jane’s attempt to break from the sect for good brings her in contact with the blue-eyed man from her nightmares, revealed to be the Satanists’ hitman and the key to a familial conspiracy that puts Jane’s trauma into sharp relief. As the title suggests, All the Colors of the Dark is a kaleidoscopic visual marvel exemplifying giallo’s greatest stylistic impulses: dizzying camera-work, hallucinatory outbursts of sex and violence, ’70s-chic production design, beautiful women wearing beautiful clothes holding sharp objects, and plenty of candy apple-red blood splatter to go around. The music, composed by giallo favorite Bruno Nicolai, taps into a similarly dreamy atmosphere popularized by close friend Ennio Morricone. Before prog-rock band Goblin reinvented the sound of giallo for Argento’s Suspiria, Morricone and Nicolai set the standard for groovy, avant-garde orchestral scores in the genre.

Nicolai also scored Fenech and Hilton’s next film together, Giuliano Carnimeo’s (under the pseudonym Anthony Ascott) The Case of the Bloody Iris in 1972. It’s Carnimeo’s only giallo yet it’s one of the most consistently entertaining and visually intoxicating entries to come out of a genre known for its extravagant visual language. As glamorous young fashion model Jennifer Lansbury, Fenech once again finds herself running from an evil sex cult hellbent on controlling her life. Along with her wise-cracking modeling friend Marilyn (Paola Quattrini, an absolute hoot), Jennifer moves into a recently vacated apartment in an expensive high-rise designed by hemophobic architect Andrea Antinori (Hilton). Their discounted new abode comes with a catch of course — the previous tenant, a Black erotic dancer named Mizar (Carla Brait), drowned in her bathtub after witnessing the murder of a call girl in the building’s elevator.

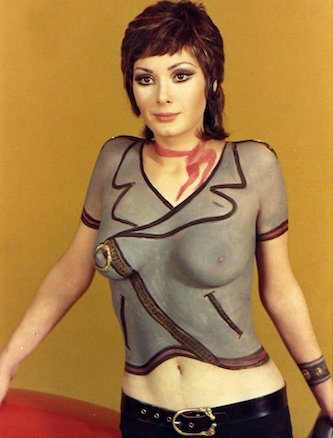

Edwige French in The Case of the Bloody Iris (1972)

With a killer on the loose and her abusive ex-husband Adam (Ben Carrá) desperate to bring her back into his sex cult, Jennifer grows increasingly paranoid of her surroundings and whom she can trust. Her conviction that Adam is behind the killings is shattered when Marilyn finds him stabbed to death in their apartment, a bloodstained iris carefully placed on the floor as a personalized calling card to Jennifer. Compared to All the Colors of the Dark, The Case of the Bloody Iris is a fairly traditional giallo: it is more in the vein of an Agatha Christie murder mystery than a supernaturally tinged psychodrama. Though Jennifer’s cat-and-mouse game with the killer is the central narrative focus, a significant amount of time is spent on the police investigation led by avid stamp collector Commissioner Enci (Giampiero Albertini) and his endearingly buffoonish detectives. An array of quirky side characters flitting in and out of the high-rise add a steady stream of humor to counterbalance the high fashion violence. Come for the bloodshed and Fenech wearing super cute outfits, stay for the flaming gay photographer who looks and sounds like Woody Allen.

Exactly who the killer is becomes apparent about halfway through, yet the screenplay (coincidentally penned by All the Colors of the Dark writer Ernesto Gastaldi) tosses so many red herrings into the mix you’re left second guessing yourself until the last five minutes. Admittedly this may deflate any sense of narrative tension on subsequent rewatch, but Iris remains thrilling thanks to Carnimeo’s strong directorial eye and Stelvio Massi’s hyper-stylized cinematography. Anxious crash zooms, bizarro angles, frantic handheld camera movement, and voyeuristic one-takes make for a vividly suspenseful visual experience rivaling Argento in peak gialli form. The fact that Iris is the only giallo in Carnimeo and Massi’s filmography is unfortunate. It’s truly one of the best-shot films to come out of the early ’70s giallo boom.

Certain aspects of any giallo are an acquired taste: post-production English dubbing, weird Italian racism (Iris especially), and era-accurate casual sexism can be off-putting for those who haven’t wandered very far from English-language horror cinema. Nevertheless, All the Colors of the Dark and The Case of the Bloody Iris are underrated giallo gems worth seeking out, representing not only the best of the genre, but Fenech’s onscreen magnetism at its strongest.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the new podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and Twitter @kuntsuragi as well as on Substack.

Tagged: All the Colors of the Dark, Dario Argento, Ernesto Gastaldi, gialli, Giuliano Carnimeo, Sergio Martino