Film Commentary: “Inland Empire” — The Dreamer Who Dreams

By Nicole Veneto

David Lynch’s Inland Empire is a provocative challenge to filmmaking as a medium of visual storytelling that’s largely gone unmatched in the 16 years since its initial release.

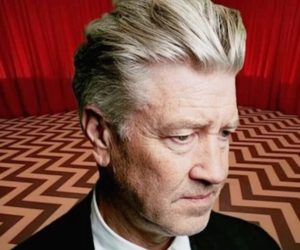

Director David Lynch

If you happened to be driving in Los Angeles around Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea on December 13th of 2006, chances are you saw one of the most bizarre yet memorable (unsuccessful) Oscar campaigns in history. At the corner of the intersection reclining in a director’s chair, David Lynch smoked cigarette after cigarette beside a large banner of an ethereally lit Laura Dern reading “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION LAURA DERN” to his left and a cow named Georgia on his right. A second sign cryptically read “WITHOUT CHEESE THERE WOULDN’T BE AN INLAND EMPIRE,” referring to his latest- (and to date last-) released feature film, Inland Empire. Rather than taking out whole page ads in Variety or industry trade magazines to promote Dern’s vividly demented yet multilayered performance, David Lynch did what David Lynch does best: be a madman.

The stunt’s become something of a meme among online cinephiles, perfectly encapsulating Lynch’s charmingly Midwestern eccentricities and artistic affinity toward the strange, the surreal, and the existentially troubling throughout his 50-plus -year career. A film as unconventional as Inland Empire merited an equally oddball awards campaign, even if the movie and its leading actress ended up being snubbed for Oscar gold (and they were). It took until 2020 for Dern to finally receive a long-overdue win for Best Supporting Actress in Marriage Story. Lynch, who’d been nominated for Best Director several times for The Elephant Man, Blue Velvet, and Mulholland Drive, received a conciliatory Honorary Academy Award that same year, presented to him by Dern alongside her Blue Velvet co-stars Isabella Rosselini and Kyle MacLachlan.

It should come as little to no surprise that David Lynch is my favorite filmmaker. I hold him and his filmography (Twin Peaks especially) in as high regard as I do Hideaki Anno and Neon Genesis Evangelion, an equally enigmatic creator/creation whose distinctive approach to art and storytelling pushes the limits of visual narrative media toward deeper, more primal meanings and observations. Although Lynch stepped behind the camera to direct all 18 episodes of Twin Peaks: The Return in 2017, his focus has gradually shifted away from filmmaking since Inland Empire and to more personal artistic endeavors like sculpture, music, and providing daily weather reports on YouTube from his sunny Los Angeles art studio.

When Janus Films announced a new 4K remaster of Inland Empire would be touring across the country, I knew I couldn’t pass up what could be my only opportunity to see and review a Lynch film in theaters. I bought a matinee ticket the afternoon before Inland Empire ended its run at The Brattle and faithfully seated myself in the second row so I could experience the full brunt of Lynchian insanity for three gloriously heady hours (that and because a disastrous late-night screening of Possession in November taught me it’s best to sit as close as possible to the screen if I didn’t want disruptive patrons occluding my view on their walk to the bathroom).

Considered Lynch’s most impenetrable and experimental film, Inland Empire is unique within the director’s oeuvre for looking, as WBUR’s Sean Burns hilariously described it, “like it was photographed inside a toilet.” Supplanting the sumptuous texture of film stock for the garish cinematography of mid-aughts digital video, Lynch shot Inland Empire on and off for nearly three years with a handheld consumer-grade Sony PD-150. Visually, it resembles an amateur porno or a no-budget horror movie only released on bargain-bin Mill Creek DVD six-packs, a far cry from Peter Deming’s lush cinematography in Mulholland Drive and Lost Highway. But, like everything Lynch touches, he manipulates the medium toward strengthening his own artistic vision. There’s an uncanniness to obsolete digital video that the found footage trend kickstarted by 2007’s Paranormal Activity failed to exploit. This aesthetic no-man’s-land — between the cinematic look of film and the low-resolution visuals of early YouTube videos — troubles the fragile boundary between fiction and reality. Appreciating this territory is key to experiencing, not merely watching, Inland Empire, arguably the closest thing to a live-feed from someone’s nightmares as we’ll ever get.

Laura Dern in Inland Empire. Photo: Janus Films

Understandably, a number of people worried this quality would be lost in the remastering process with HD conversion and AI upscaling. Inland Empire 4K looks different compared to the original standard-definition print, in the sense that it’s got more depth to it: the colors are richer and crisper and there’s a more distinctive contrast between light and darkness that’s noticeably lost to pixelization on my personal DVD copy. A subtle layer of film grain has been laid over the footage to help with noise reduction, and the audio track’s been cleaned up as well. Lynch described the new remaster as a “much better” looking version of the film that remains “true to the same ideas” and creative spontaneity of the original release. Still, Inland Empire is a daunting cinematic challenge that even well-versed Lynch fans find difficult to decipher. Neither longtime collaborator Dern nor co-star Justin Theroux had any idea what the hell was going on in the movie they made together. Searching for clear, cogent meaning or straightforward answers in anything Lynch does is a fool’s errand, and David’s never been one for explaining himself. He’s the ultimate “show, don’t tell” filmmaker in this respect, leaving meaning making and interpretation up to viewers. But if you’re familiar enough with Lynch’s visual grammar and recurring pet themes, Inland Empire opens itself up as a dark labyrinth of Lynchian signification where the boundaries between waking reality and filmic nightmare are obliterated.

The key to what makes something “Lynchian” lies in the associative connection Lynch forges between movies and dreams. In his chapter on the director’s conceptualization of the “strange” in The Weird and the Eerie, the late Mark Fisher noted that “Lynch’s customary preoccupation with dreams and the oneiric is … refracted and redoubled by the mediated and manufactured dreams of the Dream Factory, Hollywood.” In Lynch’s mind, dreams are the primal stuff of celluloid; the unconscious serves as cinema’s reservoir of symbols, making the most potent cinematic experience akin to a waking dream. Like Mulholland Drive, Inland Empire puts this ouroboric dynamic front and center as its central narrative conflict. Unlike Mulholland Drive however, there is no definitive line separating the film’s reality from the actresses’ cinematic fantasies. This is reflected in an Upanishads proverb Lynch frequently opened screenings of Inland Empire with (and was later quoted by Monica Bellucci in episode 14 of Twin Peaks: The Return): “We are like the spider. We weave our life and then move along in it. We are like the dreamer who dreams and then lives in the dream.”

Ostensibly, the main plot of Inland Empire follows actress Nikki Grace (Dern in truly the best performance of her career) as she prepares for the coveted role of Sue Blue in director Kingsley Stewart’s (Jeremy Irons) film On High in Blue Tomorrows opposite charismatic leading man Devon Burke (Theroux). At the start of production, Stewart reveals that the movie is actually a remake of an unfinished German-Polish film, 47, rumored to be cursed due to the murder of the two leads. This triggers a nightmarish metaphysical crisis of identity for Nikki. She begins to dissolve into the role of Sue, a “woman in trouble,” whose affair with Burke’s character, Billy Side, gradually splinters Nikki/Sue into different personalities, time periods, and planes of existence. Nikki’s fragmenting psyche is the metaphorical spider in this equation, weaving a character together and then becoming lost in the ensuing performance (which may not be a performance at all). Nikki’s “reality” and the film’s “fiction” collapse in on themselves so that one tunnels into and eventually subsumes the other.

If you approach Inland Empire with the sort of associative logic that dreams typically operate on, then even its most disparate parts (hookers on the Hollywood Walk of Fame) and surreal non sequiturs (the “lost girl” watching Lynch’s short Rabbits in room 47) become indispensable to the overall experience of movie-watching. The concept of a “door between worlds” is a recurring motif throughout Lynch’s filmography; it establishes a one-to-one connection between dreams/nightmares and cinema. In Twin Peaks, this motif is visualized in the Black Lodge’s flowing red movie theater curtains. Similarly, in Inland Empire, doors and windows are thresholds between scenes, mystical gateways the bridge Nikki’s “reality” and Sue’s “fictional” existence. Around the midpoint, Dern (as Nikki) walks through a back alley door with “Axxon N” scrawled in chalk above it, leading her down a dark corridor where she inexplicably finds herself watching the first rehearsal for On High in Blue Tomorrows, which was depicted earlier in the film. And what, pray tell, does a director shout before shooting a scene? “Action!”

A scene from Inland Empire

Without a firm concept of “reality” to ground its plot in, Inland Empire establishes a metatextual relationship with viewers that echoes Nikki’s/Sue’s spiraling identity crisis. The movie’s tagline, “A woman in trouble,” doesn’t just apply to Dern’s turn of character, it could also describe most of Lynch’s movies, if not the history of cinema itself. From Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s teary visage in The Passion of Joan of Arc to Laura Palmer’s traumatized screams through the trees, the indelible image of a woman’s crying, panicked face is ground zero, the origin point for immersing audiences in the vicarious experience of film. Much of Inland Empire consists of uncomfortably tight close-ups on people’s facial expressions, made all the more uncanny thanks to the slight visual distortion of the Sony-PD 150. This is precisely why Dern’s grotesquely warped face at the climax is so unnerving (even I felt a chill run down my spine); it effectively troubles our own sense of identity as much as it does Nikki’s/Sue’s/Laura Dern’s.

Inland Empire isn’t my favorite film, nor is it my favorite Lynch film (that honor goes to the once-maligned Fire Walk with Me). But it’s undoubtedly one of the greatest artistic feats of the 21st century. It’s a provocative challenge to filmmaking as a medium of visual storytelling that’s largely gone unmatched in the 16 years since its initial release, save for a few notable moments in recent independent cinema. Ahead of Inland Empire 4K’s theater tour, buzz about a secret Lynch project premiering at this year’s Cannes Film Festival ignited a wave of speculation across social media. Even Lynch’s dismissal of the secret project as “a total rumor” wasn’t enough to dissuade the masses that he’s got nothing going on outside of weather reports and numbers of the day. (The man’s known for being cryptic, plus there’s the uncertain status of his “newest” mini-series Wisteria. Though it was given the axe by Netflix in fall 2021, keep in mind that the last time a Lynch television project was rejected, it was repurposed into Mulholland Drive.) The idea that Lynch is done making films is a depressing one, but the industry has changed dramatically since 2006: think legacy sequels/remakes/reboots, IP blockbusters shot in front of green screens, and the endless marketing opportunities provided by the multiverse. All things considered, who can blame Lynch for turning his back on filmmaking when our media landscape is so saturated with comfortable (i.e., safe) nostalgia? I, for one, don’t believe Lynch is quite done yet, and if the overwhelmingly engaged reception to Janus’s 4K remaster of Inland Empire indicates anything, I doubt he believes he’s done yet either.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the new podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and Twitter @kuntsuragi as well as on Substack.