Book Review: The Many Faces of the Muse

By Kathleen Stone

Muse upends convention by examining twenty-nine real life situations that offer a broader, and more generous, view of what a muse can be.

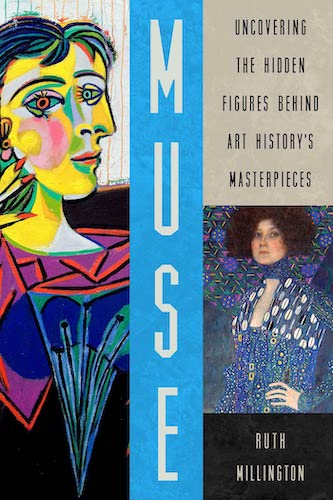

Muse: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History’s Masterpieces by Ruth Millington. Pegasus, 320 pages, $27.95.

Artistic muses have been with us a long time. As far back as ancient Greece, artists of all genres turned to these mythological creatures for inspiration. In the Italian Renaissance, that inspiration sometimes came accompanied by sexual innuendo, when painters depicted muses as nubile young women, their bodies only partially covered by dresses and drapes. On the cusp of the 21st century, Tracy Chevalier created a fictional muse in her novel Girl with a Pearl Earring, when a young woman enters the household of Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer as a maid and eventually becomes his muse and model, the inspiration for the book eponymous painting. In this telling, class distinctions, power differentials, and sexual tension inevitably come with the idea of the muse.

Artistic muses have been with us a long time. As far back as ancient Greece, artists of all genres turned to these mythological creatures for inspiration. In the Italian Renaissance, that inspiration sometimes came accompanied by sexual innuendo, when painters depicted muses as nubile young women, their bodies only partially covered by dresses and drapes. On the cusp of the 21st century, Tracy Chevalier created a fictional muse in her novel Girl with a Pearl Earring, when a young woman enters the household of Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer as a maid and eventually becomes his muse and model, the inspiration for the book eponymous painting. In this telling, class distinctions, power differentials, and sexual tension inevitably come with the idea of the muse.

In her new book, Ruth Millington aims to shake up how we think of artistic muses. Taking the premise of Chevalier’s novel as a rhetorical starting point, she questions whether the maid — powerless, submissive and female — accurately represents what it means to be a muse. “Could this characterization actually be somewhat lazy and untrue?” Millington writes, before introducing twenty-nine real life situations that offer a broader, more generous view of what a muse can be.

Some muses are artists themselves. Dora Maar, for instance, is well known as one of Pablo Picasso’s romantic partners and a subject of his paintings. Less well known is the fact that she was a photographer of some renown, and that they sometimes collaborated. Far more consequential, though, were her left-wing political views and their influence on Picasso. Millington credits Maar with broadening Picasso’s outlook, encouraging him to make human suffering an explicit subject of his work. For example, that impact can be seen in Guernica, Picasso’s seminal 1937 work. Immediately after finishing that painting, Picasso began The Weeping Woman, for which Maar posed. Although that picture is often seen by critics to be an unflattering portrait of Maar — a reflection of her troubled relationship with Picasso — Millington interprets the image differently. The suffering shown in Guernica is spread among villagers who were bombed during the Spanish civil war. In The Weeping Woman, pain is concentrated in an individual. Like many before her, Maar was both muse and model.

Another troubled relationship that inspired art was that between British painter Francis Bacon and George Dyer. The connection began in 1963 when Dyer, an unreconstructed petty thief, approached Bacon in a pub. The artist, older and already established, was captivated by Dyer’s sexual energy. As one art critic observed, “A man beyond good and evil who would stop at nothing was also the kind of man whom Bacon, in his active sexual fantasies, most hoped to meet.” In the ensuing relationship, Bacon painted numerous portraits of his lover, and paid him for posing and doing handyman work. Things unraveled after Dyer discovered that Bacon was having an affair with another man. He went to the police and accused Bacon of secreting drugs in his studio. Three years later, Dyer overdosed on alcohol and drugs. Still, Bacon continued to paint his deceased lover in what Millington characterizes as a struggle “to exorcise his sense of loss, as well as guilt, at the suicide of the great romantic muse whose shadow he could never quite escape.”

When an artist looks to herself for inspiration, can she fairly be called a muse? Millington says yes and presents Italian Baroque painter Artemesia Gentileschi as a prime example. Gentileschi often painted herself in various guises, including as a saint, the Old Testament figure Judith, even a Greek muse. In Clio, the Muse of History, from 1632, Gentileschi pictures herself as Clio. Bringing a contemporary perspective to this arrangement, Millington writes that, in the dual role of painter and model, Gentileschi undermined “the gendered mythology of artistic achievement as inherently male.” It was “an ultimate act of control. . . Through such self-possession, she wasn’t just asserting ownership of her own body, but speaking out against the male ownership of all female bodies too.”

Author Ruth Millington. Photo: Curtis Brown

The collaboration of Beyoncé and Awol Erizku, an Ethiopian-American artist who photographed the singer when she was pregnant, is an example of artistic partnership. In some photos, Beyoncé strikes poses reminiscent of those in paintings by Leonardo da Vinci, Johannes Vermeer, and Sandro Botticelli. In others, she takes on the look of an African fertility goddess or the famous Paleolithic figurine Venus of Willendorf. Millington comments “The pregnancy photo shoot was a clever collaboration for both artist and muse, who were allied in their diasporic strategy to create a mixtape of iconography, which exalts motherhood to its fullness.” The photographer, Millington continues, ensured the singer looked divine and “adoration certainly came in the form of over eleven million likes when Beyoncé posted the photos of her veiled as Black Venus on Instagram.”

These are just four of the book’s examples of a muse. Unanswered questions hover over them and the remaining twenty-five. For instance, what does Millington make of the parallels, in terms of class, power, and sexual desire, between the imagined relationship between Vermeer and his maid and the real relationship between Bacon and Dyer? Did Beyoncé calculate that artistic photographs of her pregnant body might boost sales of her music? And does that matter? Was Gentileschi consciously speaking on behalf of all women and their bodily autonomy, and how do we know? Doesn’t an artist’s self contribute to every creation, at least to some degree? By going on a quest to stake out a position that’s defiantly different from conventional conceptions of a muse, these and other questions are raised but left unanswered. Had they been addressed, Muse could have been a more complex, nuanced, and ultimately influential re-envisioning of history.

Kathleen Stone is the author of They Called Us Girls: Stories of Female Ambition from Suffrage to Mad Men, published in March 2022 by Cynren Press. Her website is kathleencstone.com.